Elizabeth Strout found success by returning to her roots

Published 12:00 am Thursday, March 15, 2018

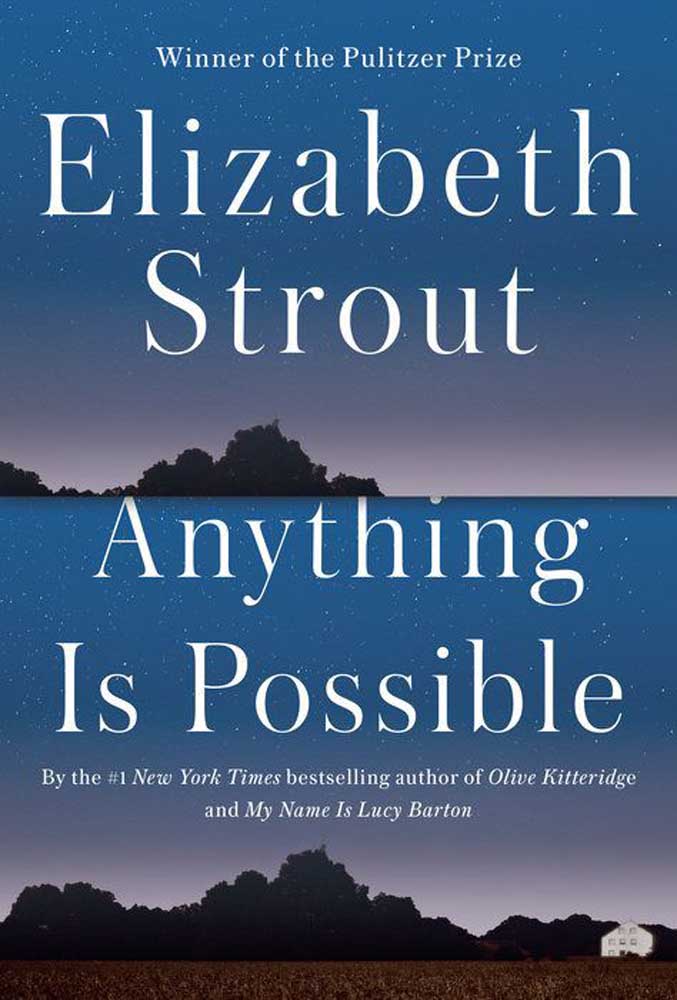

- Elizabeth Strout's latest novel, "Anything is Possible," was released in April 2017. It explores the damage parents do to their children and the consequences that follow from the perspectives of various people revolving around the central character, Lucy Barton (the protagonist from Strout's previous novel). (Submitted cover art)

Elizabeth Strout’s parents — a college professor and a high school teacher — didn’t allow TV or newspapers in the house when she was growing up in small towns in Maine and New Hampshire. Instead, her mother encouraged reading books and novels and gave Strout notebooks in which to write. Losing herself in those stories and relating to the characters in them is what first inspired her to become an author.

Strout will discuss her life as a writer and why she believes fiction matters at the Deschutes Public Library Foundation’s final 2017-18 Author! Author! presentation on Friday in Bend.

After graduating from Bates College in 1977 with a degree in English, Strout earned a law degree at Syracuse University, then moved to New York City. But she quickly realized a legal career held no allure and became determined to pursue her true passion — writing — while also teaching at a community college. A dozen years later, she was approaching age 40 and still had very little published. But where many other aspiring writers would have raised a white flag, Strout soldiered on.

“I always, from a very young age knew I was a writer and I could teach myself to write,” said Strout. “There was certainly a point when I wondered why it wasn’t happening and it was hard getting rejection after rejection. But I realized that the work just wasn’t good enough.”

After chafing within the narrow boundaries of her childhood in New England, Strout initially tried to write about the life and people she witnessed after she relocated to New York. But as years passed and the rejections mounted, she began to see she didn’t know New York well enough to really inhabit those characters.

“I think there had been a little low-level nostalgia for New England going on for a while too,” she said. “So finally I realized, let’s go back to New England.”

That’s when the pieces of the puzzle finally began to align for Strout.

Her first novel, “Amy and Isabelle,” about a fraught relationship between a mother and daughter living in the fictional mill town of Shirley Falls, Maine, started as a short story. But it began to grow as Strout returned to her roots in its themes and settings. She revised and expanded the story into a novel that she finally believed was a good book. However, with few contacts in the publishing world, she couldn’t even find an agent or publisher to read it.

Strout eventually called Daniel Menaker, the former fiction editor at The New Yorker magazine who had gone on to work at Random House publishing. Although he had rejected the short stories Strout previously submitted to The New Yorker, Menaker had always been encouraging and remembered her work. He agreed to read her manuscript and loved it.

“I got five calls from agents the next day because they’d heard a publisher was interested in the book,” Strout said wryly.

Published in 1998, “Amy and Isabelle” received critical acclaim, became a best-seller and was adapted into a movie. But it was Strout’s third novel, published in 2008, that really rocketed her into the literary stratosphere. “Olive Kitteridge” is 13 interrelated stories set in the fictional coastal town of Crosby, Maine, creating a multidimensional portrait of the prickly title character. It became another best-seller, won the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for fiction and was adapted into an Emmy-winning miniseries starring Frances McDormand. It has since gone on to sell more than a million copies worldwide.

After working for so long with no recognition, it was something of a shock for Strout to find herself in the limelight.

“I wasn’t prepared for it,” she admits. “It was terrifying, the experience of going from complete oblivion to running around on these book tours. I was privately very frightened, but I just dealt with it — I’m from New England,” she said.

Strout has now published six novels and a collection of essays. Her most recent novel, “Anything is Possible,” was released in April 2017.

She hopes her long but ultimately successful struggle to get her work published inspires others writers.

“I’m the poster child for rejection,” she said. “I mean, seriously, you know — I was 41 when (“Amy and Isabelle”) came out, I think. I remember reading that Raymond Carver said he kept writing long after it made sense to stop, and thinking to myself, ‘Uh oh, I’ve already been doing this for much longer than him,’” she said laughing.

Now 62 years old, Strout’s advice to other would-be writers is to keep reading really good work and do whatever is necessary to train themselves to read and write.

“Just don’t stop writing,” she said. After a thoughtful pause, she added a caveat. “And if you do stop, then it’s OK, because you probably didn’t want to do it as much as you thought you did.”