Cutting edge heart procedure increasing at St. Charles Bend

Published 12:00 am Thursday, March 22, 2018

- Cutting edge heart procedure increasing at St. Charles Bend

When Lee Williams went to the hospital for an aortic valve replacement last week, his CB radio friends across the country set up a network to spread news of how the procedure went and to track his recovery. They weren’t expecting he’d be back at the radio controls just two days later.

“I’m back!” he told them once his deep, booming voice recovered. “I’m ready to raise hell, hate and discontent!”

Williams, 78, is one of a select group of patients at St. Charles Bend to have undergone transcatheter aortic valve replacement, a cutting-edge, minimally invasive procedure to replace a heart valve without open heart surgery.

The procedure provides an option for patients who would otherwise face a 50 percent chance of death within two years but are unable or unwilling to undergo surgery.

“I told them there was no way they were going to crack my chest open,” he said at his home in Prineville on Tuesday. “I wasn’t going for that.”

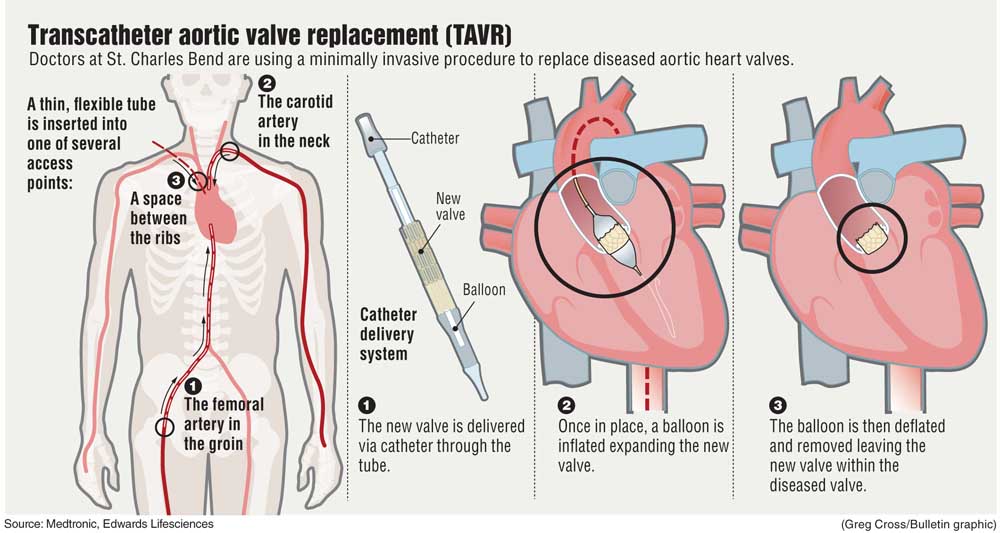

The procedure delivers the new valve by snaking a catheter through the patient’s blood vessels into the heart, then using a balloon to expand the valve and secure its scaffolding in place. It’s similar to the way doctors place stents to open up clogged coronary arteries.

Since the procedure was first tried in 2002, equipment and techniques have improved so much that patients now have comparable if not better outcomes than with open heart surgery.

That has many doctors wondering whether the procedure should become the standard way to replace heart valves and waiting to see how long the new valves will last.

Currently, Medicare, which pays for the vast majority of valve replacements in the U.S., will only cover the procedures for higher risk patients.

“That will probably change in the next three years,” said Dr. Matt Slater, a cardiothoracic surgeon at St. Charles Bend, who replaced Williams’ valve. “The technology is better; outcomes are better, and people want it. The vast majority go home the next day.”

It’s still rare for a community hospital the size of St. Charles to have a structural heart team that can fix valves and plug holes in the heart through tiny incisions. But the techniques are becoming increasingly available outside of large academic hospitals.

Slater came to St. Charles two years ago to build a structural heart team that includes cardiac surgeons, vascular surgeons, cardiologists, anesthesiologists and specially trained staff who specialize in such minimally invasive procedures. They work primarily in a hybrid operating room with a surgical team on hand in case something goes wrong and they have to switch to an open procedure instead.

Slater and the St. Charles structural heart team performed some 40 transcatheter aortic procedures in 2017, and expect to complete 50 to 60 cases this year. Aortic valve replacements at the hospital are now evenly split between open and transcatheter procedures.

“We’re doing more aggregate cases, but this has also allowed us to do aortic surgery in one group of patients that were inoperable,” Slater said. “They would have never had anything.”

That includes Williams, a lifelong smoker. Trying open heart surgery, even if he agreed to it, would have been “a bad idea,” Slater said.

Generally, transcatheter procedures are done by accessing the femoral artery in the patient’s groin. But Williams’ blood vessels were too narrow for the device. He had been previously treated for an abdominal aortic aneurysm, and that increased the risk doctors might dislodge blood clots along the way to the heart. Instead, Slater and his team went through the carotid artery in his neck.

Williams underwent the procedure under moderate sedation, which lowers the risk of stroke or other cognitive complications compared to general anesthesia.

“As our brain ages, our brain is very sensitive to anesthetics, and you can have adverse or overreactions to it,” said Dr. Sonia Shishido, a cardiac anesthesiologist at St. Charles. “We do anesthetics all the time, but it does affect these people.”

Using moderate sedation also eliminates the need for a breathing tube.

“This is a really big jump in technology, and some people aren’t even aware of it yet” she said. “You can walk into a hospital and get a valve replaced through a small incision, not even have general anesthetic and you can walk out the next day. You’re not going to go to cardiac rehab, and you’re not going to be on blood thinners.”

Trials are now underway to test the procedure in low-risk patients. The experience with moderate-risk patients suggests low-risk patients might have even better outcomes. But that also raises concern about the durability of the valves.

“There’s still a question of longevity,” said Dr. Jai Raman, a professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Oregon Health & Sciences University.

The valves are made from cow or pig heart tissue, just like the biological valves used in open procedures.

“Traditionally, these valves would last for eight to 10 years,” Raman said. “But now they are scrunched up into small configurations and then being unfurled in the heart. My expectation is that the valve would last for five to six or seven years.”

Slater is more optimistic.

“I don’t think the data set is complete yet,” he said. “But they’re not failing at some ridiculous rate that everybody has be reoperated on.”

Early studies have not found durability concerns, but because the procedure was first done almost exclusively among high-risk patients with a short life expectancy, long term data on the valves is limited. Studies examining TAVR in intermediate and low-risk patients will now track outcomes for up to 10 years, giving doctors a better idea of how long the valves will last. That’s particularly important if doctors expand the number of patients undergoing transcatheter replacement instead of open surgery, as lower risk patients could outlive their valves.

Currently younger patients often get mechanical heart valves, which last longer, but require the patient to take blood thinners to prevent strokes.

Outcomes and durability of the transcatheter valves have been moving targets, as doctors continue to perfect their techniques and manufacturers upgrade the devices. By the time a study is completed, manufacturers have come up with a new and improved version. The first TAVR systems were the size of a thumb, while newer models are now down to the size of a pen.

“Despite all the fancy improvement in technology and the better deployment tools that we have, the underlying valve is still the same,” Raman said. “So I don’t think it will ever be used, and should not at this stage be used, in patients who are low-risk.”

Doctors are also getting better at managing the stroke risk during the procedures. When the catheter is pushed through the patient’s arteries, there’s always the possibility of scraping off a blood clot that can travel to the brain and cause a stroke. Newer studies, however, are showing the stroke risk is declining.

The shorter hospital stay has helped bring costs down as well. The two commercially available transcatheter valves, manufactured by Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences, cost about $33,000 each, compared to just $4,000 for valves used in open surgery.

“It’s a super expensive piece of technology. It’s like an origami folded valve,” Slater said. “The companies are also super smart at figuring out pricing. They basically know the hospital is going to save money on length of stay and they just charge more for the valve.”

An analysis presented at a medical conference in October found that while the transcatheter procedure cost about $22,000 more than an open surgery, mainly due to higher cost for the valve, shorter lengths of stay and fewer complications brought difference down to only $2,900 higher than open surgery. A second analysis found that lifetime costs for transcatheter patients were nearly $10,000 less than for open surgery while quality of life for patients improved.

Hospitals have strict criteria to determine who is best suited for open surgery and who might benefit from transcatheter valve replacement. Nonetheless, some doctors worry the newer procedure might be overused, particularly if hospitals have invested in building a structural heart program.

“Because this technology is there, there’s always the temptation or risk of doing it in people where it might not be appropriate,” Raman said. “The unfortunate side effect of these things, because it’s so easy, it’s sort of unleashed the genie from the bottle, and it will be a while before we understand the full import of what happens.”

—Reporter: 541-633-2162, mhawryluk@bendbulletin.com