A story of guns, sex and a guru in Oregon

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 25, 2018

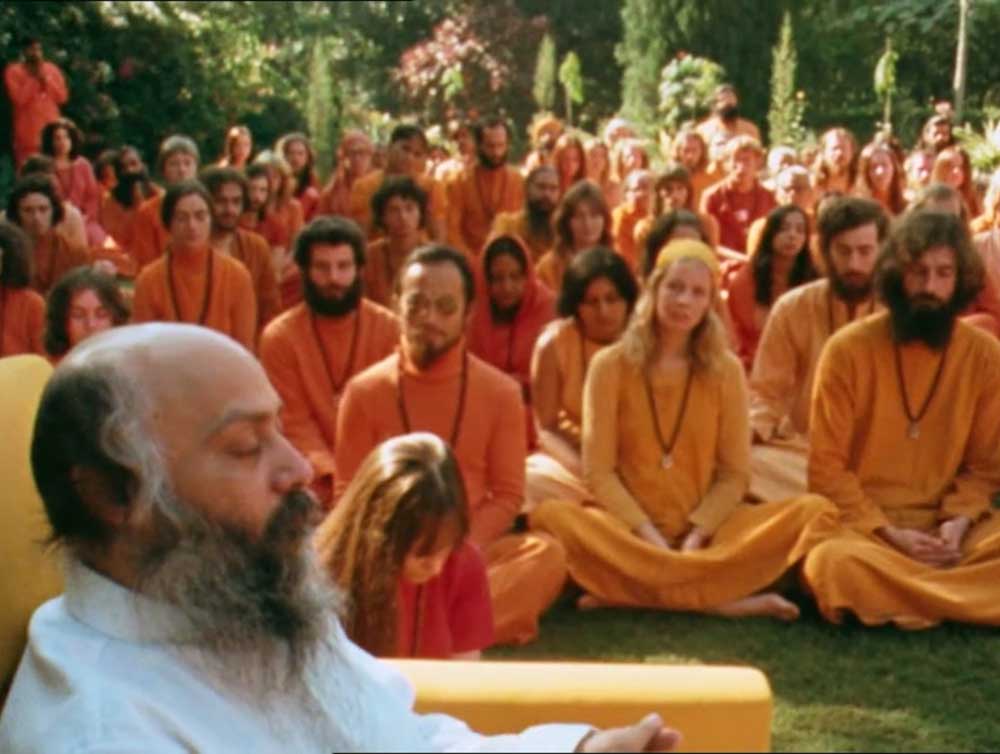

- Bhagwan Rajneesh was the leader of a cult that’s the subject of a new Netflix documentary series, “Wild Wild Country.” (Netflix)

Jane Stork and Ma Anand Sheela, on-screen throughout the six-hour documentary series “Wild Wild Country” on Netflix, look and sound like friends of your grandmother who have dropped by to reminisce about the good old days.

They don’t look like leaders of an international religious movement known for Rolls-Royces and ecstatic group sex, or women who went on the lam to Europe before serving time for crimes that include arson, wiretapping and attempted murder. It’s particularly jarring when the petite, gray-haired Stork acknowledges that she volunteered to carry out assassinations — twice — while serving the spiritual leader known as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. But that’s what their good old days entailed.

Trending

Interviews with the two women, now in their late 60s, and with Prem Niren, another former Rajneeshee leader, form the backbone of “Wild Wild Country.” It’s a history of the tumultuous years in the early 1980s when the Bhagwan’s followers bought a 63,000-acre ranch in the high desert of Oregon, built an expansive commune called Rajneeshpuram and went to war with the locals, first in the nearby town of Antelope and then with the entire state.

The filmmakers who have taken on this bizarre, complicated story are brothers Chapman and Maclain Way, both too young to remember the 30- to 35-year-old events they’re chronicling. They’ve done an impressive amount of work, amassing archival film and news clips and tracking down former Rajneesh followers as well as a number of their foes.

You sense that after that, it was all they could do to get the story down in reasonably complete and coherent fashion. They haven’t given it much of a shape or a perspective — they go from one mind-blowing event and image to the next, and seem to just adopt the point of view of whoever’s talking at the moment, reinforcing it with correspondingly bright or sad or triumphant music (which becomes increasingly intrusive). Their own attitude, as far as it can be divined, appears to be a credulous sentimentality.

But it is a great story, even if you just turn on the camera and let it roll. One incidental revelation, or reminder, is how breathlessly and exhaustively the events were reported. They were the reality TV of their time, with guns, sex, a mass poisoning and murder schemes. The events may have been playing out in the proverbial middle of nowhere, but that was the point: A movement, or cult, of thousands of post-’60s seekers in orange and purple mufti had descended upon ranchers and retirees, who took on the mantle of frontier yeomen protecting American values against foreign invasion.

The battle between the Rajneeshees and the citizens of Antelope prefigures, in a fun-house-mirror way, our current cultural and political landscape — notions of American liberty and morality were being defended against perceived (and actual) outside threats.

“They’re invading,” an Oregonian said at the time. “Maybe not with bullets, but with money and, um, immoral sex.” In the long and successful fight to get rid of Rajneeshpuram — which led to the deportation of the Bhagwan and the jailing of some of his followers — the government used immigration law, accusations of church-and-state violations and the denial of voter registration as tactics.

Trending

Paranoia and anger reigned on both sides, though, and the emotional crux of the story lies in the arrogant, tone-deaf and eventually criminal behavior of the Rajneeshees. The Ways supply ample testimony to this, along with lots of shots of the members toting semi-automatic rifles and conducting al-Qaida-style combat drills. There is also a recurring motif of the newcomers in their monochromatic attire walking around Antelope, where they co-opted the government and much of the real estate. (Some of this footage has been slowed slightly, for an “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” effect — like the heavy-handed music, another unfortunate choice.)

Within the six hours — which include more than a little padding and repetition, despite the story’s many twists — the Ways are also able to communicate some of what made the Rajneesh movement so compelling to its adherents (though the series could use more of this). The shots of smiling, dancing followers, working with seeming happiness and engaging in frenzied, naked encounter sessions, suggest a trial run for Burning Man (which began in 1986, just as Rajneeshpuram was disintegrating).

What’s most striking about “Wild Wild Country” is how present, and unyielding, the passions of the combatants remain. Mention the Bhagwan and Prem Niren still chokes up, while a rancher who led the opposition still spits out the word “evil.”

Sheela — the hot center of the five-year conflict, who now owns and operates nursing homes in Switzerland — seems nearly as imperious, impatient, contemptuous and possibly deluded (or maybe megalomaniacal) as she was at the time. She also remains a masterful performer and manipulator, and the Ways give her the first and last word. “The people of Oregon should think themselves lucky,” she says, to have had the Rajneeshees as their neighbors. In this story, no one can let it rest.