After resource plan, what’s next for Crook County?

Published 8:01 am Thursday, April 26, 2018

- After resource plan, what’s next for Crook County?

Earlier this month, Crook County leaders passed a plan designed to give county residents more say in how local public lands are managed by the federal government. However, discussions over how the plan will be implemented and what it will mean for the county’s oft-contentious relationship with its local public land managers are just getting started.

“This is a way for local government to sit at a table with the federal government on a peer-to-peer basis,” said Teresa Rodriguez, Prineville city councilor and a former chair for the Crook County National Resources PAC, the group that devised the plan.

Trending

While advocates see the county’s plan — known as the Crook County Natural Resources Policy — as an opportunity to have their voices heard and have more of a stake in how public lands are managed, environmental groups are concerned the plan is a waste of time and money, one that could harm the county’s burgeoning recreation industry.

“I think there are existing functional and legal alternatives in place already,” said Sarah Cuddy, Ochoco Mountains coordinator for Oregon Wild.

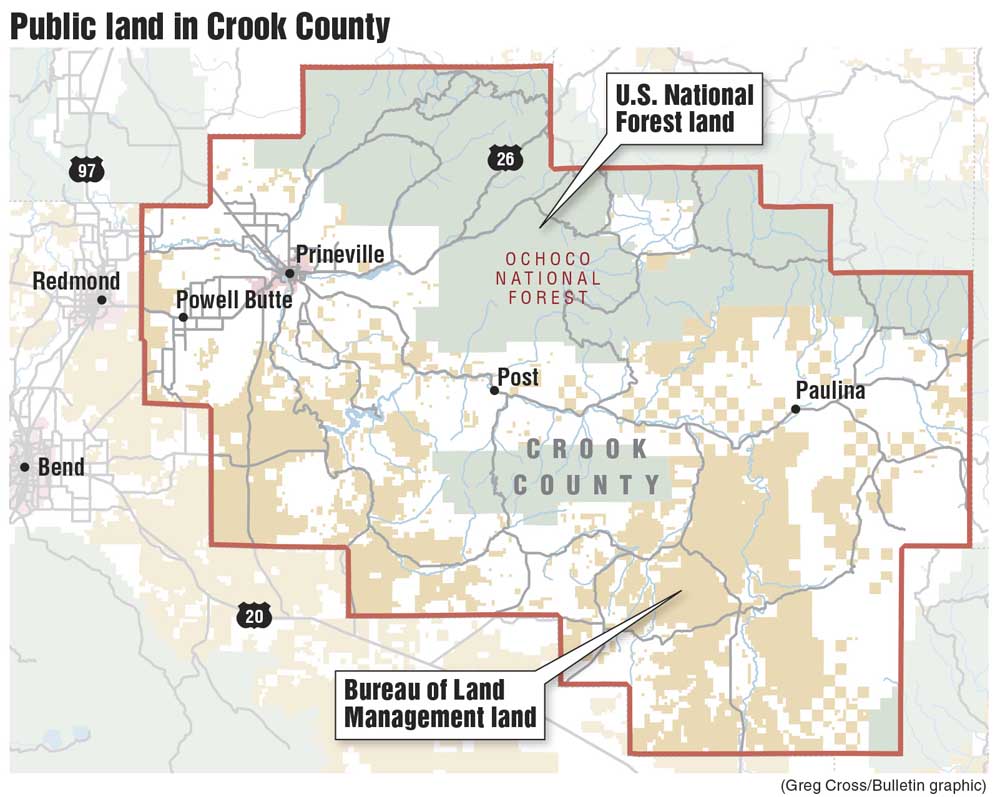

The Crook County National Resources PAC was founded in 2016 by a small group of people who were frustrated with how the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management were overseeing public land in Crook County. As with many Oregon counties located east of the Cascades, a majority of the land in Crook County is managed by federal and state agencies, which can breed resentment when that land isn’t managed to the satisfaction of local residents.

Rodriguez’s criticisms mainly centered on projects in the Ochoco National Forest, including an off-highway vehicle plan she said did not incorporate public sentiment, and several forest-thinning projects, which she said leaves areas of the forest with a tremendous amount of built-up fuel for wildfires.

“We basically have a bunch of kindling out there waiting for a wildfire,” Rodriguez said.

Both Patrick Lair, spokesman for the Ochoco National Forest and Crooked River National Grassland, and Lisa Clark, spokeswoman for the Bureau of Land Management’s Prineville District, said Monday that they hadn’t heard from county representatives since the plan passed, but added that they hoped to continue positive relationships with county residents.

Trending

“We want to continue to be good partners and good stewards,” Lair said. “We don’t necessarily see this as adversarial.”

An earlier version of the resources policy was introduced in 2016 but rejected by the Crook County Commission; county elections last November got the movement back on its feet, according to Seth Crawford, Crook County judge. Crawford also reached out to Karen Budd-Falen, a Wyoming-based land use attorney perhaps best known for representing Cliven Bundy in court in the past. Budd-Falen said the county hired her in August to look over the plan.

”She’s very knowledgeable about federal law when it comes to natural resources,” Crawford said.

Following minor revisions, the Natural Resources Policy was approved unanimously on Nov. 8. The county has 120 days after the policy was approved to appoint a citizen committee and an individual — whom Crawford termed a “natural resource manager” — to be a liaison with local officials representing federal agencies. Crawford said details, including how large the committee will be and whether the resource manager position will be voluntary or paid, remain up in the air.

In addition to articulating county priorities for how federal land should be managed with regard to mining, agriculture and recreation, the plan states that the county expects state and federal agencies to meet with county officials on an ongoing basis.

The plan relies on a federal statute known as coordination, a condition of two federal environmental policy laws that requires agencies to communicate with local governments regarding land-use planning. Budd-Falen said the statute requires federal agencies to provide an explanation for any decisions they make, which adds an extra layer of accountability that individual county residents lack.

“I just think it puts the county in a different situation,” she said.

Still, Michael Blumm, professor of law at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, said federal agencies don’t have any obligation to follow the county priorities set out in the plan, which range from mandating no reduction to grazing allotments on federal land, to ensuring that roads providing access to public lands stay open year-round.

“It’s a political move,” he said. “It’s not legally enforceable.”

Blumm, who studies environmental and natural resources law, said policies like Crook County’s are tied to the larger battle around local control of public land, which he said has been raging in the West since the 1970s and reached a crescendo in 2016 with the occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. In the 1990s, Blumm said the battleground shifted from Western states to rural counties.

In a letter mailed to Crook County’s judges, Blumm argued that federal agencies don’t have any mandate to comply with state and local plans, and cited court cases dating back to the 19th century that indicate that federal goals supersede local mandates on public land.

“Adopting a county plan without observing the federal laws … would be a disservice to Crook County residents,” Blumm wrote.

Additionally, Cuddy warned the plan could prompt future lawsuits, if the plan causes a local branch of a federal agency to violate federal law. Even if the plan can be enforced without litigation, Cuddy said certain aspects of it, including the mandate that the federal government not restrict lands used for mining, logging and agriculture, could end up doing damage to the county’s growing recreation sector.

“I think it just doesn’t have an eye toward the future,” she said.

Rodriguez said the purpose of the plan is not to pre-empt federal law or to make a set of unrealistic demands, but merely to create a framework for residents to better articulate their frustrations about federal land management.

“I don’t think this is a silver bullet,” Rodriguez said. “It’s a living, breathing document.”

— Reporter: 541-617-7818, shamway@bendbulletin.com