Proven treatment for opioid addiction underused

Published 12:46 pm Tuesday, July 24, 2018

- Proven treatment for opioid addiction underused

Jaymes was out of second chances. He had peed dirty twice and his parole officer had had enough.

“Dude, this stuff has really got you,” the parole officer told him. “You come in next week and you’re still high, you’re going away for a year.”

His life was unraveling again. After more than a dozen arrests for drug possession and petty theft, after progressing from marijuana to prescription pain pills, from smoking heroin to injecting it, after eight months in prison that forced him into sobriety, less than six months later he was once again facing time behind bars.

But this time it would be different. Jaymes, who asked not to be identified by his full name, had met a woman and had fallen hard for her. He couldn’t stand the notion of being away from her for months.

“I need help,” he pleaded with his father. “I need to get on Subs.”

His father took him to a doctor who prescribed Suboxone, or Subs as it’s known on the street. The medication combines buprenorphine and naloxone to prevent the cravings and withdrawal that come with opioid addiction while slashing the risk of an overdose death. “Ever since I got on that, I did really well,” Jaymes said. “I got off parole a year later. I hadn’t touched it again.”

As the nation struggles with an ongoing opioid epidemic that has killed hundreds of thousands and ruined countless lives, one of the few proven solutions to opioid addiction has been woefully underused. Medications like buprenorphine and methadone have been shown to reduce illicit drug use and prevent overdose deaths. For those with a history of opioid use, the drugs do not cause a high, allowing them to resume normal lives. They may represent the best bang for the buck for addressing the crisis.

But as opioids themselves, these medications remain tainted by the stigma of addiction. Many in the recovery community consider their use as trading one addiction for another, and tell those taking the medications they aren’t really clean. Most doctors remain unwilling to prescribe them in fear of filling their waiting rooms with addicts or facing the scrutiny of federal law enforcement officials. And when doctors do choose to offer the treatment, they face significant regulatory and insurance barriers. As a result, there are nearly a million fewer treatment slots than there are individuals with opioid addictions.

Meanwhile, opioid overdose deaths continue to pile up.

“It boggles my mind that someone can call themselves an addiction specialist or an addiction treatment program and not have the most effective known treatments available,” said Dr. Richard Saitz, a professor at Boston University Schools of Medicine and Public Health and senior editor of the Journal of Addiction Medicine. “This is the thing we know can save lives.”

Path to addiction

Jaymes, who has lived in Bend for about four years, started smoking pot at age 14 during his freshman year of high school in a California beach town. When he graduated, his circle of surfer friends started sharing Norcos and Oxy 80s, powerful opioid pain relievers that were among the most commonly abused prescription drugs.

The group soon moved onto heroin, which was cheaper and easier to find, first smoking it off tin foil, and eventually injecting it.

“I always told myself I’ll never stick a needle in my arm. But before I knew it, I was doing it, and once I did, I’d never go back to smoking,” he said. “It just hits you instantly. It’s all at once and the pleasure it gives you is just ridiculous. It was over from then on.”

He was working odd jobs at first, able to keep functioning for two to three days in between getting high. But once he was hooked, those highs would last only eight hours, and soon he’d be desperate to find another $80 for a tiny balloon filled with a gram of heroin.

“The last thing I wanted to do was be without that stuff. I planned my life around it,” he said. “I tried to get as many connects as possible, to meet people that knew their source.”

He would drive around town with one eye open for surfboards or other items he could steal off porches and pawn for drug money. He became a dealer himself, buying a couple of grams, using half and reselling the rest to finance the next score.

When he couldn’t find any heroin locally, he drove down to Los Angeles, combing Skid Row at Seventh and Alameda.

“I’d look for people who looked strung out,” he said. “Sure enough I’d find them, no problem. I’d get out of my car, and within 10 minutes I was on my way to getting loaded.”

In April 2007, he and a girlfriend passed out in a car after getting high. The cops found their drugs, and he was sent to jail. He endured a miserable three days of withdrawal.

“You can’t do anything in there. You just got to rot and suffer, not sleeping, hating life,” he said.

For the next four years he bounced in and out of jail and rehab programs, none of which helped him kick his habit. His first court-mandated rehab was a Salvation Army abstinence-based program that had him working nine hours a day in a warehouse sorting donations.

“Eventually I’d meet up with another addict. … Let’s get high,” he said. “For me, it was an introduction to more fellow addicts to get supply from. Nobody really wanted to get clean because it was forced on you. To me those are a complete failure.”

A better way

Dr. Marvin Seppala had once been a firm believer in the power of the abstinence approach. As medical director of the Minnesota-based Hazelden Foundation, he relied on the combination of counseling and group therapy as part of the 12-step model developed by Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous. But in 2007, he left the clinic to establish an outpatient clinic in Beaverton that used buprenorphine to treat opioid disorders.

“I found it to be really effective,” he said.

When he returned to Hazelden in 2009, he met significant resistance when he suggested the clinic add medication to its treatment tools. But the clinic was feeling the effects of the opioid epidemic, with a surge of new patients addicted to pain pills or heroin. Yet, 25 percent of those with opioid use disorders were dropping out of the treatment program early. And when they left, many relapsed and died.

“It was kind of an ethical imperative to really look into this and try something different,” he said. “We had a lot of resistance at first.”

Fewer than 20 percent of addiction treatment programs nationwide offer addiction medication, which Seppala attributes to old biases. Most of those working in treatment programs are in recovery themselves, and many had bad experiences being treated for alcohol or drug addiction with poorly matched medications. Others judge addiction medication by their experiences with methadone clinics, which have been effective for many, but can also become a magnet for drug dealers looking for new clients.

Eventually Hazelden’s leaders relented and agreed to offer patients addiction medication. Patients with opioid use disorders are now told their treatment should include either Suboxone or Vivitrol, a non-opioid that binds to opioid receptors, along with their traditional 12-step program. Some 34 percent chose Suboxone and another 41 percent chose Vivitrol.

One in 4 refuse medication. That’s particularly true of clients who have been forced into treatment by the judicial system or their parents, but aren’t really motivated to quit.

“They don’t even want to be here, let alone be abstinent from opioids,” Seppala said. “Then finally the brain starts to heal enough that they start to see it for themselves, and that’s when we have the chance to make those interventions.”

Within six months, the foundation’s dropout rate for clients with opioid use disorder dropped from 25 percent to 7 percent. Under the new approach, 71 percent were abstinent after six months, compared with 52 percent before the clinics started offering medications and other opioid-specific supports.

Despite such success, clients taking addiction medications still face considerable stigma in the recovery community after their discharge. Groups such as Narcotics Anonymous and other 12-step programs often tell attendees they’re not really in recovery if they’re taking addiction medications. Many won’t start calculating their “time clean” until they stop using. Some meetings ban those taking such medications from speaking.

Hazelden, which merged with the Betty Ford Center in 2014 and has two treatment facilities in Oregon, now runs its departing clients through “stigma management training” before they leave.

“One option is to not say anything about it. The other is to talk about it, but be in a meeting that’s friendly to medication or to find a sponsor or peers that are not surprised or offended by it and will report you,” Seppala said. “But even so, it’s a fairly constant battle for patients that are facing these sorts of negative attitudes about it on a regular basis.”

Clients also face difficulty finding sober housing that will permit the use of Suboxone. Some argue they don’t have enough staffing to secure those medications, posing a risk that other residents or staff could relapse using it. Hazelden has struggled to find sober housing in many of its communities, and in some cases has had to store the medication at its clinic, requiring clients to return each day to take it.

As a result, drug users continue to battle stigma well after their illicit drug use ends. Many deal with the stress and criticism with the only escape they know: another pill, another needle.

Doing time

In June 2011, Jaymes woke to the banging of the police baton on his truck window. It was 8 a.m. and a crowd had gathered around the vehicle. The engine had been running since he had found a safe little spot to shoot up in his neighborhood six hours earlier.

Jaymes looked down to see a needle still sticking out of his arm.

“They had already offered me all the county-funded rehabs they could,” he said. “It was time to go upstate.”

Jaymes was convicted of a felony and sentenced to 16 months in state prison. He was out in eight months, his longest period of sobriety since he finished high school. When he was released, he petitioned the court to allow him to serve out his parole with his mother in Bend, away from his familiar drug scene and the circle of friends who were still using. Forced to stay in Orange County, he stayed off drugs for five months before running into an old friend and making another bad decision.

“I can’t blame it on him. I made the choice to get high again, and it took off from there,” he said.

It was a few months later that his parole officer caught on and gave him the ultimatum. Jaymes had bought Suboxone on the street from time to time when he couldn’t find heroin. He knew it worked. But now with real motivation to quit, he took the medication daily. By the end of 2013, he completed his parole. The next day he moved up to Bend.

Limited access

Doctors face few impediments to prescribing opioids despite the risk for addiction. Addiction medications, on the other hand, are entangled within a thicket of regulations. Methadone can be dispensed only at authorized clinics, requiring patients to come once a day to take their medication under direct observation. Buprenorphine can be dispensed from a physician’s office to treat addiction, but only if the doctor completes eight hours of training and applies for a special waiver.

Even then, the doctor can prescribe to only 30 patients for the first year and must reapply to expand to up to 100 in the second year or 275 in the third.

A recent survey found that about a third of pain specialists prescribe Suboxone for the treatment of pain without a waiver, although that represents an unapproved, off-label use of the medication. Addiction experts say that’s more likely to occur with chronic pain patients who develop an addiction to prescription opioid painkillers and have trouble tapering down to meet new prescribing guidelines, rather than users of illicit drugs like heroin. And a large number of Suboxone prescriptions by a doctor without a waiver would almost certainly attract DEA attention.

According to researchers at the University of Kentucky, fewer than 30,000 doctors had waivers to prescribe buprenorphine, including Suboxone, at the start of 2016, and fewer than 6,400 could see up to 100 patients. On the other hand, more than 900,000 U.S. physicians can write prescriptions for painkillers like Oxycontin, Percocet or Vicodin, that have been blamed for starting the opioid crisis.

That’s left a huge treatment gap, where only 1 in 10 people addicted to opioids are able to access treatment. The 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found some 1.9 million Americans were addicted to prescription pain pills and another 500,000 to heroin.

Even if all the physicians with waivers treated to their maximum allowable capacity, they could care for only 1.5 million patients.

But even when physicians have waivers, few see as many patients as their waivers allow.

A 2017 survey found that physicians with waivers who weren’t prescribing to their 100-patient maximum treated an average of 31 patients, but still rejected about half of new-patient requests each month.

The added hurdles for buprenorphine suggest the drugs are particularly complex to prescribe or have the potential for great patient harm. But doctors who prescribe the medications say they’re no more dangerous than many other drugs that come with no prescribing restrictions.

“That’s always been bothersome to me,” said Dr. Nathan Boddie, an internist at Mosaic Medical and a Bend city councilor who is running for the state Legislature. He is one of only a handful of local doctors with a waiver.

“We prescribe lots of medications that have side effects and really risky profiles,” he said, “and we do that with the regular medical licensing and DEA number.”

It’s unclear just how much the Suboxone restrictions are keeping physicians from prescribing those medications. It may be doctors are more reluctant to open their waiting rooms to people with addictions, or to admit that they’re already there.

Doctors at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland recently created teams of caregivers and peers in recovery to intervene with patients admitted to the hospital with complications of opioid use disorder. Project IMPACT aims to start them on addiction medication while still in the hospital and then hand them off to providers in the community who can continue their treatment. They found that hospitalization was often a wake-up call for drug users and more than 80 percent of patients were open to working with a team. Of those, 60 percent started on addiction medications in the hospital.

But the program leaders found that IMPACT also had a profound effect on physician and nurse opinions.

“It’s just been remarkable from a provider perspective,” said Dr. Honora Englander, a professor of medicine at OHSU who heads the project. “We can really see that treatment changes culture.”

Doctors who once were skeptical about the notion of treating addiction as an illness had a change of heart, telling researchers they now see addiction as a chronic disease that “actually has treatments” and that “failure to treat addiction is a failure to be a good doctor.”

“Some of that is absolutely the value of having an expert team in the hospital which sort of legitimizes the disease,” she said. “But some of it is seeing the effect of medications and how they work.”

When British researchers reviewed the evidence around the use of methadone or buprenorphine for treating opioid use disorders early this year, they concluded the medications reduced the risk of death by two-thirds.

“When you think about medications for any condition that can reduce mortality by two-thirds?” Englander said. “Nothing we do is that effective.”

Failed approach

It’s even more remarkable how ineffective the standard addiction treatments are. Detox and abstinence work for only 6 percent to 10 percent of people who try it. Parents are often wooed by expensive celebrity rehab residential programs, thinking they represent the very best care available for their children.

“There are countless treatment rehab centers around the country that are willing to take your $10,000 for 30 days that will never address the underlying brain issue and leave that child at an even higher risk of dying of an overdose the week they get back,” said Dr. Todd Korthuis, an internist and addiction medicine specialist at OHSU.

“To pretend that you can treat opioid use disorder without medicines is really to ignore the overwhelming evidence.”

The National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers, which represents about 320 members with 800 treatment locations across the U.S., has as its official policy that both medication and abstinence-based approaches have value, and that patients should be allowed to determine which treatment is best for them.

“There’s a fear for some of the more traditional treatment providers that there will be a push to medication only,” said Peter Thomas, membership manager for the group. “We don’t support the use of exclusively medication. … Medication alone is not a good solution.”

Providing addiction medication in an outpatient setting runs around $3,000 to $4,000 a year and is generally covered by insurance plans, although coverage hurdles also exist.

“It’s not a magic bullet,” said Dr. Benjamin Schwartz, founder of Recovery Works Northwest, which provides Suboxone and counseling at two Portland-area locations. “But it’s far and away the best tool for opioids that is out there.”

Until recently, Central Oregon has had very little access to medication-assisted therapy.

More primary care doctors have acquired the waivers to prescribe buprenorphine in recent years, and the opening of the Bend Treatment Center in 2015 expanded access to Suboxone and methadone locally. The subsidies for insurance provided by the Affordable Care Act and the expansion of Medicaid in Oregon have provided coverage for many of those with addictions, and safety-net clinics such as Mosaic Medical and the La Pine Community Clinic have added addiction treatment capacity. More medical schools are including training on addiction, and as a result, newer graduates are getting waivers at higher rates.

The medication is still much more readily available in larger cities such as Portland or even Bend than in more rural parts of the state. Dr. Laura Pennavaria, now the medical director for the St. Charles Medical Group in Bend, once had a patient from Madras who would drive 72 miles to her clinic in La Pine to get her Suboxone.

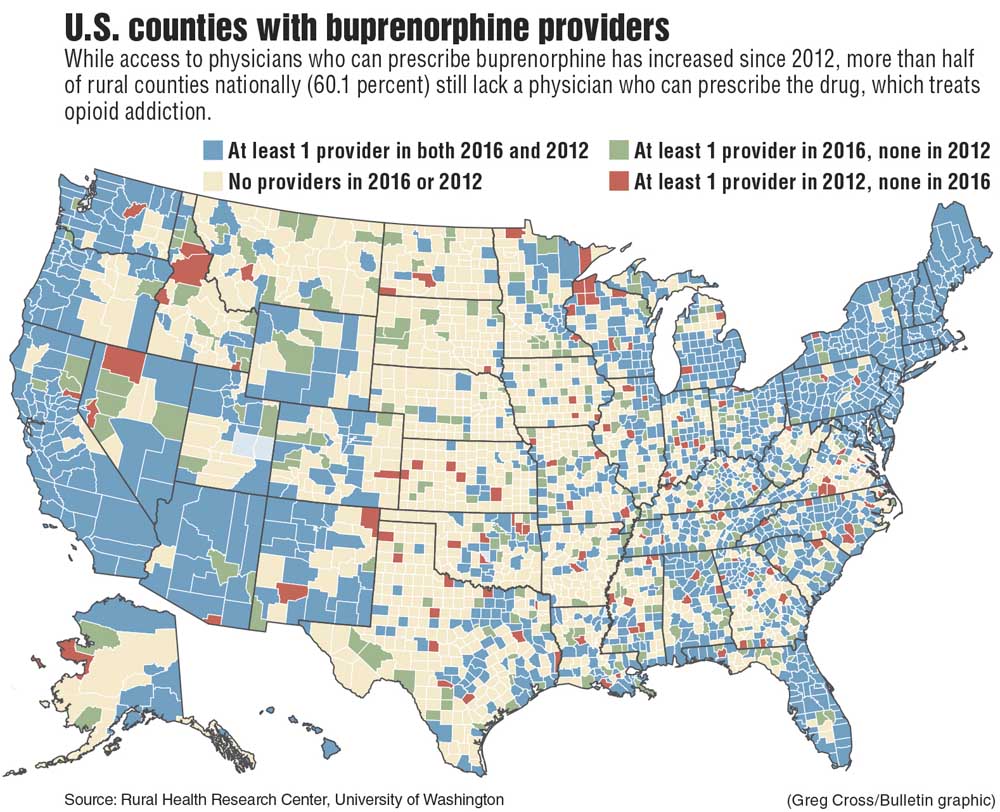

A study published earlier this year in the Annals of Family Medicine found that 60 percent of rural counties do not have a single waivered physician, and more than half of the waivered physicians nationwide are not actually treating any patients. Some states, including Oregon, will now allow nurse practitioners and physician assistants to apply for the waivers.

And when people are ready for treatment, the window to act can be vanishingly small.

“If they are scrambling for some way out,” Pennavaria said, “it really behooves the medical community to have access to a way out for those folks.”

Another relapse

Unable to find a doctor who prescribed Suboxone in Bend, Jaymes weaned himself off the medication after four months. As withdrawal set in, he asked his co-workers at a gas station for Oxycodone.

“Before I knew it, I was wanting more and more pills and trying to look for dope in the park,” he said. One day, unable to find anything in Bend, he drove to Portland rehashing his old L.A. Skid Row strategy.

“I went to the methadone clinic. I knew junkies hang out there. I found one, got me a connect and it was on,” he said.

For the next three months, he was driving to Portland nearly every other day. Some days, he barely had enough money for gas to get him there.

“I’ll figure it out on the way home,” he told himself. “As long as I’m high, I’ll go sponge for money at the gas station. I don’t care.”

In September 2014, he was driving back from Portland high on heroin, nodding off as he drove U.S. Highway 20. He drifted into the opposite lane and narrowly missed hitting a car head-on. A truck driver who saw the near miss called the police. He was pulled over as he entered Bend.

Charged with reckless endangerment and driving under the influence, he would eventually serve two weeks in the county jail. Upon his release, he got high one last time before finding a doctor who would get him back on Suboxone. He’s been sober ever since.

“It’s something that’s subconsciously in your head. You know you’re not going to get high if you use, it’s going to be a waste,” he said. “It does the job and you don’t get high, but you don’t crave.”

Different drugs

Saitz, the addiction journal editor, said the view of addiction medicines as trading one addiction for another stems from a misunderstanding of how these drugs work. Most people with an opioid use disorder are using short-acting opioids.

“If you take an oxycodone tablet or if you inject heroin — or even fentanyl if that’s what you get — the level goes up quickly and then it goes back down quickly, and in between uses, you may have none of that left in your system,” he said.

At first, the flood of opioids causes euphoria, and with regular use, a feeling of withdrawal — muscles aches and sweating, vomiting and diarrhea, anxiety and sleeplessness — in between. Over time, as the brain adjusts to the regular supply of opioids, the highs begin to diminish, and the withdrawal gets worse. They don’t feel good with drug use anymore, they just feel nothing.

“What they’re feeling now after using for a long time is the difference between feeling terrible and feeling close to normal,” Saitz said. “When they use, they might have a brief euphoric moment but they’re really not getting that much of a high anymore. They’re really trying to avoid feeling terrible.”

Both methadone and buprenorphine, on the other hand, are long-acting opioids that stay in the system for days without the up-and-down cycle of short-acting opioids.

“Your body just gets used to a steady and constant level, and because your body gets used to it, you just feel normal,” he said.

Clinicians have also discovered that people with opioid use disorders have abnormalities in their brains, although it’s unclear whether those are caused by the drug use or predate it. In some people, their brains can heal once the drug use stops. But in others, those changes persist, and without some sort of opioid, they cannot function normally.

Some have interpreted that as an ongoing addiction, but it doesn’t meet the agreed-upon definition of addiction: the continued use of drugs despite harmful consequences.

“Many of us in the addiction community maintain that people who are taking buprenorphine or methadone, or naltrexone for that matter, and are not using illicit drugs, are abstinent,” Saitz said. “They’re abstinent and in recovery.”

Suboxone also has a ceiling effect, where taking more of the medication won’t increase the impact of the opioids and create a high. With their minds no longer dulled by opioids, people start to feel emotions, can sort through some of the personal trauma or depression they had been masking with drug use, and can get on with their lives.

“My Suboxone patients have been among my favorite patients,” Pennavaria said. “It’s so beautiful to see someone get their life back. It’s amazing to see someone get a job, get their marriage back, get themselves back on their feet. And people almost uniformly are so grateful. They say, ‘You saved my life.’”

Patients describe Suboxone as a miracle drug that allows them to pry themselves free from the grip of addiction. The medication removes them from the Russian roulette of buying heroin on the streets, never knowing whether the next hit may be their last.

“I have a handful of these kids. I’m just trying to keep them alive. And I’m thinking maybe they wouldn’t be if they did not have Suboxone,” said Dr. Jamie McAllister, a primary care physician in Bend with a certification in addiction medicine. “And if we can keep them alive, maybe we can get them to the next step.”

In October, President Donald Trump declared the opioid epidemic a public health emergency, a move that included allowing doctors to prescribe addiction medications by telemedicine. But the declaration did not provide additional funds to expand access to addiction treatment, as many advocates had hoped it would. The administration’s opioid commission called for a rapid increase in access to addiction medication in its interim report, but the final report this month pulled back on that recommendation.

Last month, Dr. Scott Gottlieb, director of the Food and Drug Administration, told a congressional panel that addiction medications would be a cornerstone of the agency’s response to the opioid crisis.

“Now, I know this will make some people uncomfortable,” he said. “FDA will join efforts to break the stigma associated with medications used for addictions treatment. This means taking a more active role in speaking out about the proper use of the drugs.”

It’s a major turnaround for the Trump administration, whose now-departed Health and Human Services Secretary Dr. Tom Price described such medications as “substituting one opioid for another” in May. Gottlieb went to great lengths in his testimony to describe the difference between addiction and dependence.

“Someone who neglects family, has trouble holding a job or commits crimes to obtain opioids has an addiction,” he said. “But someone who is physically dependent on opioids as a result of the treatment of pain, but now is not craving more or harming themselves or others, is not addicted.”

Those words describe perfectly Jaymes’ transformation.

“It’s allowed me to go back to work and have a clear head and function and be productive, really, and not be trying to steal … all the time,” he said. “It was a lifesaver.”

He started out taking an 8-milligram Suboxone pill once a day, but has slowly weaned himself down to 2 milligrams a day. He enrolled in college and is engaged to be married to the woman who was the motivation for starting Suboxone in the first place.

“It’s amazing how far I’ve come. If you could see the way I used to live back then, it’s night and day,” he said. “I’ll never forget where I was.”

Without Suboxone, Jaymes believes he would likely be dead now.

“I almost died a few times. More times than I can count on two hands,” he said. “I have had 34 or 36 close friends that we would just hang out all the time down south that are all dead now. Good people when they weren’t high. They’re all dead. They’re still dying.”

(Editor’s note: This article has been corrected. Statistics related to medication assisted drug treatment within Hazelden Betty Ford were incorrect. The name of The National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers has also been corrected. The Bulletin regrets the errors.)

— Reporter: 541-633-2162, mhawryluk@bendbulletin.com

“There are countless treatment rehab centers around the country that are willing to take your $10,000 for 30 days that will never address the underlying brain issue and leave that child at an even higher risk of dying of an overdose the week they get back. To pretend that you can treat opioid use disorder without medicines is really to ignore the overwhelming evidence.”— Dr. Todd Korthuis, addiction medicine specialist at Oregon Health & Science University

Medications used to treat opioid addiction

Methadone

Dispensing limits: Licensed opioid treatment programs

Effectiveness*: 74-80 percent

Form: Daily pill, liquid or wafers

Buprenorphine (Subutex)

Buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone)

Dispensed limits: Outpatient clinics if provider has waiver, licensed opioid treatment programs

Effectiveness*: 60-90 percent

Form: Daily tablet, film or dissolvable pill, or six-month implantable device

Naltrexone (Vivitrol)

Dispensing limits: no restrictions

Effectiveness*: 10-21 percent

Form: Daily pill or monthly injectable

*Effectiveness defined as retention in treatment in 12 months, with significant reduction or elimination of illicit drug use.

Source: California Health Foundation

Markian Hawryluk is reporting this series during a yearlong Reporting Fellowship on Health Care Performance sponsored by the Association of Health Care Journalists and supported by The Commonwealth Fund. For the rest of the series so far, visit bendbulletin.com/opioids.