Sunriver man receives Navy’s top honorary civilian award

Published 12:00 am Saturday, July 28, 2018

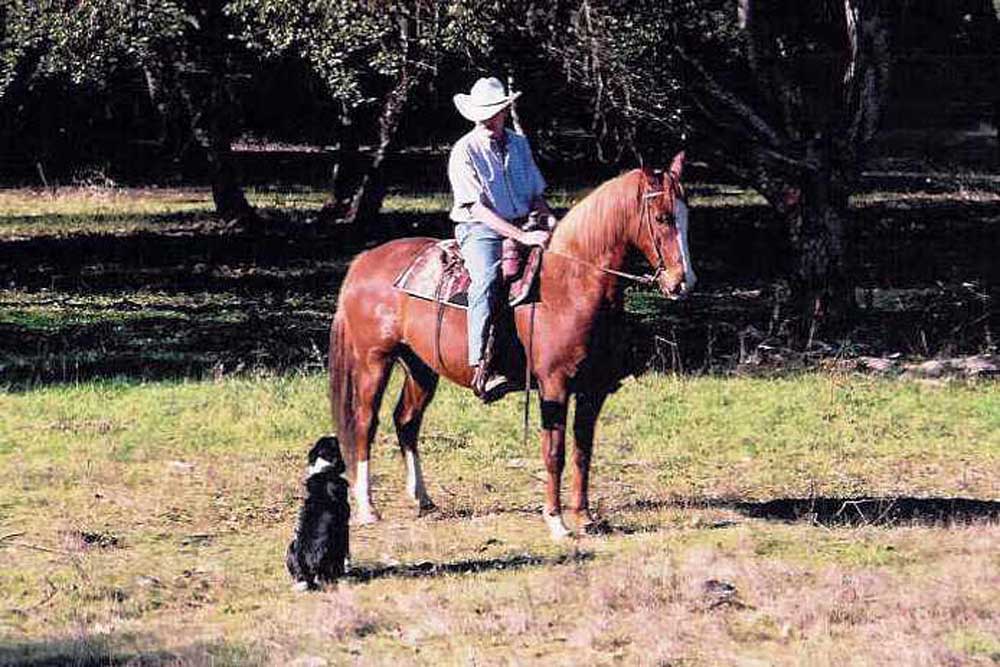

- ABOVE: Gerald Brown (third from the left) stands with Air Force pilots in Kuwait City. There, Brown and his team visited several operations areas while planning efficiency improvements in wartime air transport. LEFT: Brown sits on his horse, Kalvin, while interacting with his border collie.(Submitted photos)

The way Gerald Brown gushes about his chestnut brown horse and marvels at his backyard birds, you would never guess he’s been a high-level operations researcher for the Navy making critical decisions about the bombs used in combat.

The summertime Sunriver resident has been recognized by the Navy as being a national asset — for the second time.

For his operations research, Brown recently received the Navy Distinguished Civilian Service Award — the highest honorary award granted to a civilian by the U.S. Navy. But you might not know that by the rumpled certificate he’ll hand you during a visit to his home in Sunriver.

“Here, keep it. It’s just a photocopy,” Brown said during an in-person interview. The actual award, which the Navy presented at a 500-person ceremony in June, included a tray-size plaque, a large medal meant to be worn with a tuxedo, a recognition pin to wear on a sports jacket and a framed certificate. He keeps the hardware in his other home, where he lives with his wife, Nancy Brown, in Pebble Beach, California.

But Gerald Brown, who is retired and declined to give his age because he says it’s top secret, isn’t into what he calls “Yea, me! walls,” or personal shrines.

“On special occasions, I’m supposed to wear a certain insignia, and Nancy comes in and says, ‘You look like a Russian general. Take that off,’” he said with a laugh. Throughout the year, Brown volunteers full time at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, since retiring earlier this year. The Browns spend three to four months each summer at the Sunriver home they own, sometimes visiting during the winter when nordic ski conditions are ripe for shuffling through the nearby forest. Their border collie, Ni-Joh-Li, whose name is Navajo for good listener, tags along, Brown said. And don’t get Brown started about how fond he is of his chestnut-colored horse Kalvin, who he recently rode to Broken Top mountain in the Three Sisters Wilderness with his wife, also an equestrian.

Summer is Brown’s time to unwind.

“Now I’m only working 50 hours a week instead of 80,” Brown said with a chuckle.

Brown’s work is tough to explain. He has an “elevator explanation” for brief social interactions.

“When I’m at a cowboy bar (in Central Oregon) and someone asks what I do, I tell them I work in operations research. In the civilian world, that’s called ‘The science of better.’ It’s used by virtually all large companies to find ways of doing business (more efficiently). In the military it’s called ‘How to plan to fight and win your nation’s wars.’”

During the Gulf War, Brown and a colleague developed a scheduling program for cargo planes in Iraq and Afghanistan. The goal was to maximize the lift of cargo and people and get them off the road because they were getting blown up. His work did not go unnoticed.

He won his first Navy Distinguished Civilian Service Award in 2009 for 33 years of service, but his work during the Gulf War was cited in particular.

He’d go into detail, but some of his work is confidential.

“It’s very satisfying getting a letter from a general saying, ‘We did an analysis, and you saved ‘k’ lives last month,’” Brown said, declining to say exactly how many lives. “‘Well done.’”

To help the Navy figure out the most cost-effective or safest way of doing something, Brown uses applied mathematics or, as he likes to call it, “optimization-based decision support.” Brown gave an example of how he has used statistics in his workplace, but it reads like a bizarre test question:

Let’s say you’re naval personnel in charge of ordering 1,000 bombs. Before you place the order, how many bombs — and which ones — do you detonate to test the quality of the lot?

“If the lot size is 1,000 bombs, you may get away with just testing 10,” Brown said. But deciding which of those 10 is where Brown’s statistical procedure comes in.

“You don’t want to pick the 10 bombs that are right on top or the 10 bombs in the bright painted boxes. You want to pick the bombs randomly and without bias. If we (detonate these 10 bombs), we can make an … inference test. You’re inferring from those what the population will look like.”

Measures like these save lots of taxpayers’ money, he added.

Brown discovered a love of science while attending high school at a U.S. Army base in Italy in the 1960s. One science teacher was very influential.

“He changed my life. I wouldn’t say I was the mischievous type, but he kept challenging me, throwing things two feet ahead of me. He kept doing that for several years, and I think that is what ignited my interest. I originally thought I would become (an Air Force or airline) pilot.”

Brown didn’t take to math until college.

“I had a couple professors that seemed to be magicians,” he said. “‘How did you come up with this?’ I asked them. They said I didn’t have the fundamentals that I needed in mathematics, so they directed me to more and more math courses.”

While earning his doctoral degree at UCLA, Brown had to choose whether to tilt its focus toward the managerial or mathematical end of things. He chose management, which has helped his consulting work in the private sector.

“Once I got a taste for success, I was able to dedicate a hell of a lot of hours, thanks to Nancy and others,” Brown said. “Hard work is what separates fantasy from reality.”

Despite having worked 80-hour weeks for decades, Brown said he wouldn’t change a thing. When he has free time, he also enjoys flying his Cessna airplane.

“You live hard and party hard,” Brown said. “The people I work with, the students, they all do this. That’s average. One of my students called me at O-dark-30 and said, ‘Sir, you’ve got to come in and see this.’”

Brown dressed and drove to their classified laboratory. The student was ecstatic about a new idea he’d developed while working on a missile defense thesis. Instead of transporting missile defense systems on Navy cruisers, why not station the systems on land?

“Many ideas seem obvious in hindsight, but where were you when it was a blank space on a piece of paper?” Brown said with a laugh.

At the naval school, the students, who are all military officers, earn “million-dollar degrees,” Brown said, describing how any new ideas they come up with become naval patents. Some of Brown’s current students have deployed in combat more than five times.

“They come to us with varied experiences, and many of them have real passions to fix problems they’ve encountered in the field,” Brown said. “Our job is to show them the path to fix those problems.”

Jeff Kline, now a retired captain of the Navy and faculty member at the Naval Postgraduate School, was one of Brown’s former students in the early 1990s. Kline remembers how Brown would alleviate his students’ long laboratory hours with the Halloween candy that he scored through consultation work with the Mars candy company.

“We greatly appreciated that,” Kline said with a chuckle.

Once Kline graduated, he took command of a hydrofoil patrol boat. He immediately applied some of the lessons Brown taught in the classroom to better save onboard fuel. Kline and others later joined Brown in formalizing the protocol into a programmable tool that is now a Navy patent. It’s one of two patents Brown has delivered to the Navy.

Pressed for more insight into what makes Brown tick, Kline laughed.

“The fun facts about Jerry Brown are all up in Oregon,” he said. “All we hear about are his stories of horse riding and that sort of thing. Kalvin (the horse) is well known to us.”

— Reporter: 541-617-7816, pmadsen@bendbulletin.com