Winning isn’t everything in new era of college football

Published 12:00 am Friday, August 3, 2018

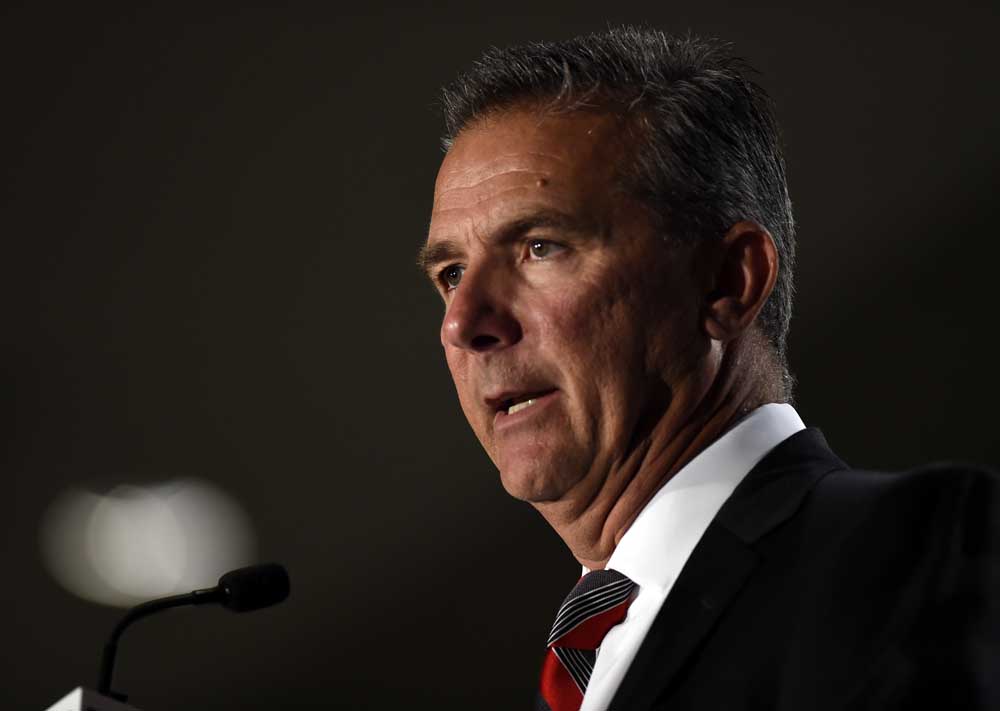

- Meyer

Until this week, Ohio State’s Urban Meyer was among the most valuable coaches in college football.

He has shepherded Heisman Trophy winners and top draft picks, like Tim Tebow and Alex Smith, and has won relentlessly, guiding his teams at Florida and then Ohio State to three national championships since 2006. In his six seasons in Columbus, Meyer’s Buckeyes have gone 73-8, giving him a higher winning percentage than Nick Saban has in 11 seasons at Alabama.

Trending

Then, in a matter of hours Wednesday, he became arguably the most radioactive coach in the game. Ohio State placed Meyer, 54, on paid administrative leave while it investigates whether he knew about domestic violence allegations against a longtime assistant.

The move signaled that Meyer’s immaculate on-field performance may not be enough to save his job.

On Thursday the university’s board of trustees announced that it had formed a special, independent board for the investigation, saying the working group will direct the investigative team.

That Meyer’s job hangs in the balance despite superlative coaching and no known risk of NCAA sanctions is the latest example of a shift in big-time college sports.

In earlier years, teams stomached just about anything from the head coach so long as he kept the victories coming. Losing was the only sin. Not anymore.

“Twenty years ago, there would not have been the sensitivities that there are today,” said Bill Carr, a former Florida athletic director who advises on coaching searches. “In my opinion, that has dramatically changed.”

Trending

Richard Southall, a professor of sport management at the University of South Carolina who specializes in sports ethics, sped up the timeline: “I think we are at a different point than we were five years ago,” he said.

Meyer’s swift downfall began when independent journalist Brett McMurphy reported Wednesday morning on his Facebook page that Meyer’s wife knew of a 2015 incident in which Meyer’s longtime assistant, Zach Smith, was accused of shoving and choking his ex-wife, Courtney Smith. The article cited text messages that spoke of Meyer’s having confronted Zach Smith about it. Last week, Meyer, who fired Smith after a recent trespassing charge and protection order were reported, denied knowing about it.

In a statement Wednesday, Ohio State said, “We are focused on supporting our players and on getting to the truth as expeditiously as possible.” Ohio State’s investigation could eventually clear Meyer, allowing him to return to the sidelines. Given the current climate, that may prove problematic.

Winning is still valued in college sports — astronomical salaries indicate it is valued more than ever. As increased revenue has leveled the playing field for the less-heralded colleges, eroding the advantages blue-blood programs used to enjoy, the importance of having an elite coach has grown.

But times are changing. Art Briles almost single-handedly made Baylor’s football program relevant, but after an investigation revealed a culture of coddling players accused of and charged with sexual assault, he was dismissed in May 2015.

Hall of Fame men’s basketball coach Rick Pitino withstood both personal and NCAA scandals at Louisville but was forced out after last year’s college basketball recruiting indictments.

Hugh Freeze led Mississippi to its second 10-win football season since 1971, but phone records showing he had called an escort service were enough to end his tenure in Oxford last year.

If, in the past, winning was the only thing that mattered, these days it increasingly seems to resemble the easy part — particularly if the coach has an established track record.

“A guy like Urban Meyer, Mike Krzyzewski, Rick Pitino, you’re never going to fire them because they have a bad year, or two or three bad years,” said Bob Lattinville, an agent with the business law firm Spencer Fane. “They have tenure — unless something like this happens.”

Meyer’s problems come on the heels of other athletics scandals at Ohio State, including a lawsuit alleging that in 2014 an assistant coach had an inappropriate sexual relationship with a 16-year-old diver who said there was no adequate way for her to report it, and the university’s announcement last month that an investigation had uncovered more than 100 former students who say Richard Strauss, a former team doctor, sexually abused them.

Even before the #MeToo movement began last fall there was a particular allergy in college sports, Southall said, to misconduct that is sexual or includes violence against women. The contract extension Meyer signed this year included language about failing to report violations of the university’s sexual misconduct policy to the Title IX office.

Such language is now common in contracts, Lattinville said.

In the 1970s and ’80s, Barry Switzer, Oklahoma’s football coach, and Bob Knight, the men’s basketball coach at Indiana, won three national titles each, as well as boatloads of games even as they ensnared themselves in the kinds of scandals that might not have been tolerated from other university employees.

Switzer was charged with insider trading (the case was dismissed). Knight minimized rape in a television interview and hurled a chair across the court during a game.

Switzer lost his job only when the Sooners were hit with severe NCAA penalties. Knight held on until 2000, and he was ousted only after he grabbed a student’s arm soon after a player accused Knight of choking him. One year later, Knight was hired by Texas Tech.

In 2002, Iowa’s basketball coach Steve Alford stood by a player accused of raping another athlete. Alford apologized in 2013.

“What happens off the field or the court,” Lattinville said, “is more likely to spell your doom than losing ballgames.”