Stats: Early deliveries up in 2017

Published 12:00 am Friday, August 17, 2018

- (Greg Cross / The Bulletin)

Doctors once thought there was little difference if babies were delivered at 37 or 38 weeks of gestation, or carried for a full 39 weeks. That led to a host of women being induced early without a medical reason. But once research showed that babies born even a week or two early are at higher risk for complications, hospitals put in place safeguards to ensure no one was delivering early without a good reason.

That risk is one of the reasons the Oregon Health Authority has tracked how many births covered by the Oregon Health Plan are elective early inductions. Regional coordinated care organizations, which provide care to OHP members, must submit data showing what percentage of their births were induced early without justification.

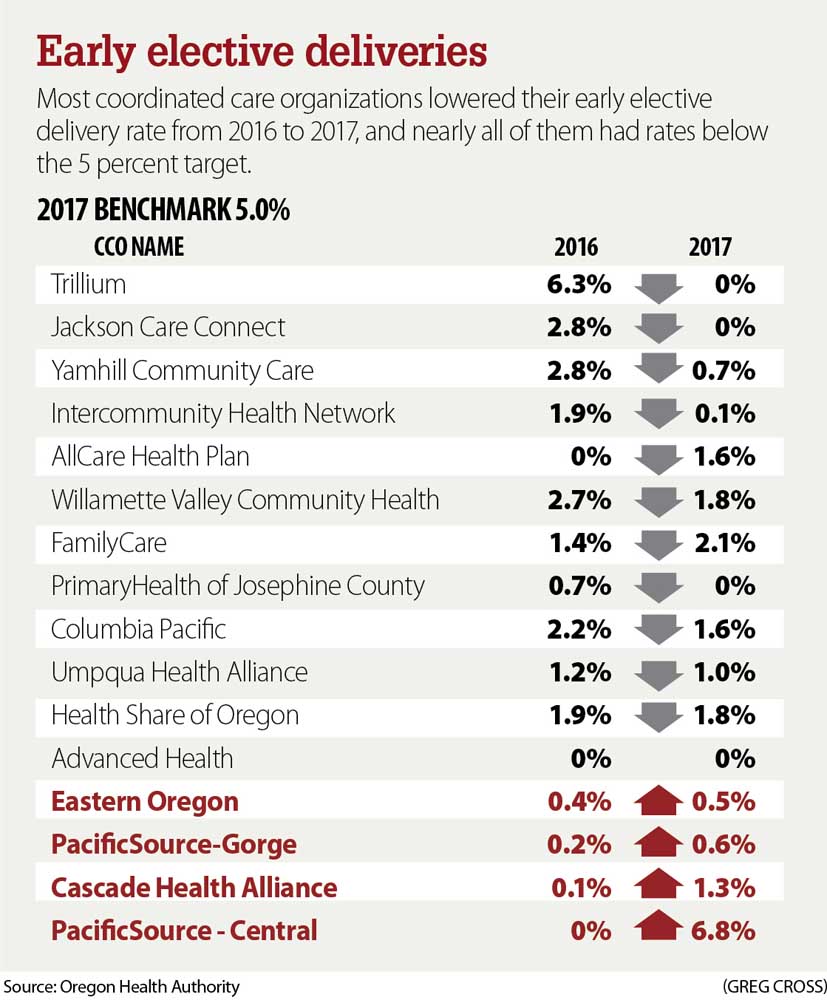

In 2017, the Central Oregon CCO, operated by PacificSource Health Plans in conjunction with the Central Oregon Health Council, saw its rate jump to 6.8 percent, after having zero the previous year.

What was behind the jump? Well, that’s a complicated question to answer.

The Central Oregon CCO has only two hospitals at which babies are routinely delivered: St. Charles Bend and Redmond. St. Charles initiated a policy in 2016 to prevent unwarranted early deliveries, including a checklist of appropriate reasons for inducing from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. They also put in protocols for a “hard stop” that required doctors to get approval for any early induction that wasn’t on the list.

Dr. Barbara Newman, medical director for the St. Charles Center for Women’s Health, says some of the early inductions in 2017 might have had legitimate medical reasons but were coded incorrectly in the health records system.

When Newman examined 2018 data at St. Charles Redmond, she found five cases that were flagged as early elective inductions. That included three cases of oligohydramnios, a condition characterized by low amniotic fluid, which protects the baby and assists its development.

“Which is one of our indications for early delivery,” Newman said. “It’s not elective.”

The doctors had used the code for low amniotic fluid, and the record system flagged those as elective early deliveries. The other cases had legitimate reasons for inducing as well, one an irregular heartbeat and the other due to preeclampsia.

Newman predicted that with increased focus on proper coding, the 2018 rate would drop significantly.

Studies show babies born the 37th week of pregnancy have double the risk of ending up in the neonatal intensive care unit. Babies born just a week early have a 50 percent higher risk.

“I’m an older OB,” Newman said. “We used to induce people at 38 weeks because that was the definition of term. Now I shudder because of those numbers. What was I doing?”

Deliveries at 34 to 36 weeks were considered near term in the 1990s. Doctors were taught that the mortality rate at 35 weeks was the same as at 39 weeks. As a result, they readily induced at the first hint of any concern.

“That led to the practice in the late ’90s, early 2000s, where we started inducing electively not just early term, at 37, 38 weeks, but the late preterm period, 36 or 35 weeks,” said Dr. Aaron Caughey, chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University.

But those tenets were based on relatively small studies. Since infant deaths are rare, those differences didn’t show up.

About 10 years ago, doctors began looking at outcomes in much larger populations and found significant differences. Outcomes improved for every additional week of gestation. Fewer babies died and fewer had health complications.

That led to an effort to create the list of appropriate reasons for inductions, and both national and state efforts to rein in elective deliveries.

In 2010, Caughey and the directors of obstetrics for Providence and Legacy hospital systems got together and agreed to stop early inductions at their hospitals. They started at their hospitals in Portland. Working with the March of Dimes, they expanded that effort across the state, getting almost every hospital in Oregon to agree to the same standard.

The only hospitals that couldn’t agree were a couple of small hospitals in eastern Oregon who only had anesthesiologists on site once a week.

They decided it would be safer to deliver at 38 weeks, than to risk a complication at a time when they weren’t staffed to handle it.

The rate of early inductions dropped from 4 percent in the three years prior to the policy change, to 2.5 percent in the first two years under the new approach.

While hospitals strive to lower their early elective inductions, experts say they shouldn’t be expected to have none. There are just too many exceptions that won’t get picked up by a checklist of appropriate reasons.

“But what about someone with some weird medical disease? It’s not going to be on the list,” Caughey said. “That’s the fudge area that gets tricky.”

There’s also the challenge of accurately dating the pregnancy.

That’s not always easy, particularly when women miss their early prenatal visits, which is more of an issue with the low-income women served by the Oregon Health Plan.

“They may not have access to care. They may not believe they’re covered for care,” Newman said. “There are language barriers, transportation barriers.”

Setting a low threshold allows for those exceptions that could otherwise put the mother and baby at risk for the sake of meeting a metric.

The elective induction rate is no longer one of the metrics used to evaluate coordinated care organization quality for payment purposes. It was retired in 2015. All but two CCOs in the state had rates below the 5 percent target.

It’s been seven years since hospitals in Oregon first agreed to the hard stop, and while rates remain low, advocates want to make sure they don’t creep higher as attention begins to wane.

“It’s something that was important and we accomplished on a statewide basis. And we’re still monitoring it,” said Joanne Rogovoy, state director of programs services for Oregon chapter of the March of Dimes. “It’s gotten pretty low, but maybe we need to revisit it.” •