A guide to wildfire preparedness and history

Published 12:00 am Saturday, September 1, 2018

- A guide to wildfire preparedness and history

The smoke may be gone for now, but wildfires — and fires set by humans — will remain a constant threat in Central Oregon. Natural causes, such as a lightning storm, can ignite a wildfire. That’s what caused the 1996 Skeleton Fire that burned a route to houses in eastern Bend.

Alternately, a fire can crop up in town, as it did on July 4 when a blaze — ignited by a man who lit an illegal firework — torched a section of Pilot Butte. A nearby apartment complex was evacuated, causing residents to flee with only the bare essentials.

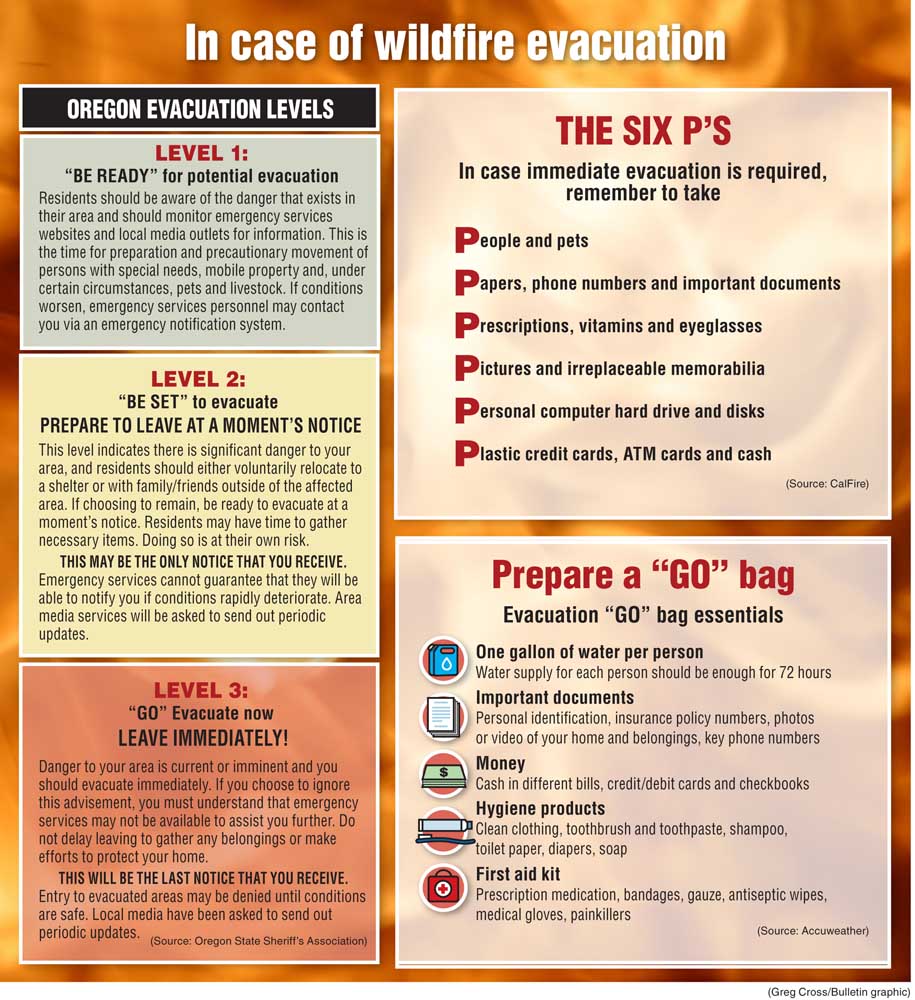

Living in a town surrounded by forestland, it’s vital to be prepared long before a fire threatens your home. Fire authorities suggest having an easy-to-reach “GO” bag packed with bottled water, important documents, money, hygiene products and a first aid kit. Know the Oregon evacuation levels: 1) Be ready. 2) Be set 3) Go. Take as many steps as possible to protect your home from fire.

Creating “defensible space” is a smart safeguard for a house. Defensible space entails clearing a 100-foot radius around your home of easily combustible material, such as dead or dying tree branches or mulch. Removing pine needles and cones from rain gutters is key, too. These measures will prevent a wildfire’s flying embers, which can travel as far as a mile, from igniting this natural fuel, said Dave Howe, Bend Fire Department spokesman. This is useful particularly for people who live in the urban-wildland interface. Because Bend is almost surrounded by public land, many people live on this cusp.

“Studies have shown that most houses do not ignite in a giant wall of flame,” Howe said. “That’s kind of the Hollywood version, and that’s not how it works.”

Evacuation decisions are made jointly by a county emergency service manager and the fire incident commander assigned to a particular fire. The incident commander is typically a ranking firefighter from the jurisdiction where fire is burning.

For example, in Bend it would be the Bend Fire Department’s on-duty battalion chief coordinating with the Deschutes County Sheriff’s Office’s emergency service manager to determine which areas are most critically in danger and issue different levels of evacuation orders. Authorities take into account a lot of variables which include wind speed and direction, fuel type, housing density, whether there is more space for fire equipment and the weather forecast, Howe said.

“They think about a myriad of factors,” Howe said. “It’s not a cookie-cutter kind of thing.”

Sheriff’s deputies and Bend Police officers then go door-to-door advising the public on the level of emergency. Local agencies use social media to spread updates on evacuation levels. They also send news media outlets reports of the latest developments. Citizens can receive emergency text notifications to their smartphones by registering with the Deschutes Alert System.

The Cloverdale Fire, which burned more than 74 acres east of Sisters, is the most recent wildfire to require an evacuation in Central Oregon. Other recent wildfire-related evacuations in Central Oregon include the Graham Fire, which originated near Lake Billy Chinook on June 21. Sparked by lightning, the Graham Fire torched more than 2,000 acres and necessitated evacuations in the nearby Three Rivers subdivision. The 21,312-acre Milli Fire, caused by lightning on Aug. 11, 2017, required hundreds of people to leave their homes in subdivisions near Sisters.

Sometimes, firefighters learn the best methods through trial and error.

In 1990, an arsonist unleashed the Awbrey Hall Fire, which scorched 3,350 acres and destroyed 22 homes on Bend’s west side. The fire’s name is owed to an out-of-town agency conflating Awbrey Butte and Aspen Hall — both near the fire’s origin, said Howe, who responded to the blaze. The Awbrey Hall Fire was a wake-up call to local fire responders, he said, which included the Bend Fire Department, the Oregon Department of Forestry, the U.S. Forest Service and private wildfire crews.

“Before that fire, we just operated on our own … (Afterward) everybody got the idea that what we were doing wasn’t working very well,” Howe said, describing how some of the department’s firefighters were excluded from the fire camp set up at Central Oregon Community College. “After the fire, we all sat down separately and together and realized that we no longer could operate in silos. We had to work together.”

The agencies began operating in a unified command. They began meeting before the fire season, and many times again throughout the hot, dry months. The agencies also synced their codes and terminology, in accordance with the National Incident Management System, Howe said.

The agencies’ ability to cooperate was soon tested.

In 1996, lightning ignited vegetation near Skeleton Cave, which gave the Skeleton Fire its name. The flames traveled from the Deschutes National Forest into the Bend Fire Department’s jurisdiction. Firefighters were ready, Howe said.

“We were collaborating much better,” he said. Nearly 20 homes were still lost. “The silver lining (to these fires) is that we got a lot better at what we do.”

— Reporter: 541-617-7816, pmadsen@bendbulletin.com