Bend physician links legalized marijuana to opioid epidemic

Published 12:00 am Thursday, September 27, 2018

- Bend physician links legalized marijuana to opioid epidemic

Several studies have found states that have legalized marijuana have lower rates of opioid overdoses. That has led many to speculate that broader access to cannabis could be a key to reversing the opioid epidemic.

But a new analysis is calling that correlation into question and suggesting that legalization could be making the overdose crisis worse.

Trending

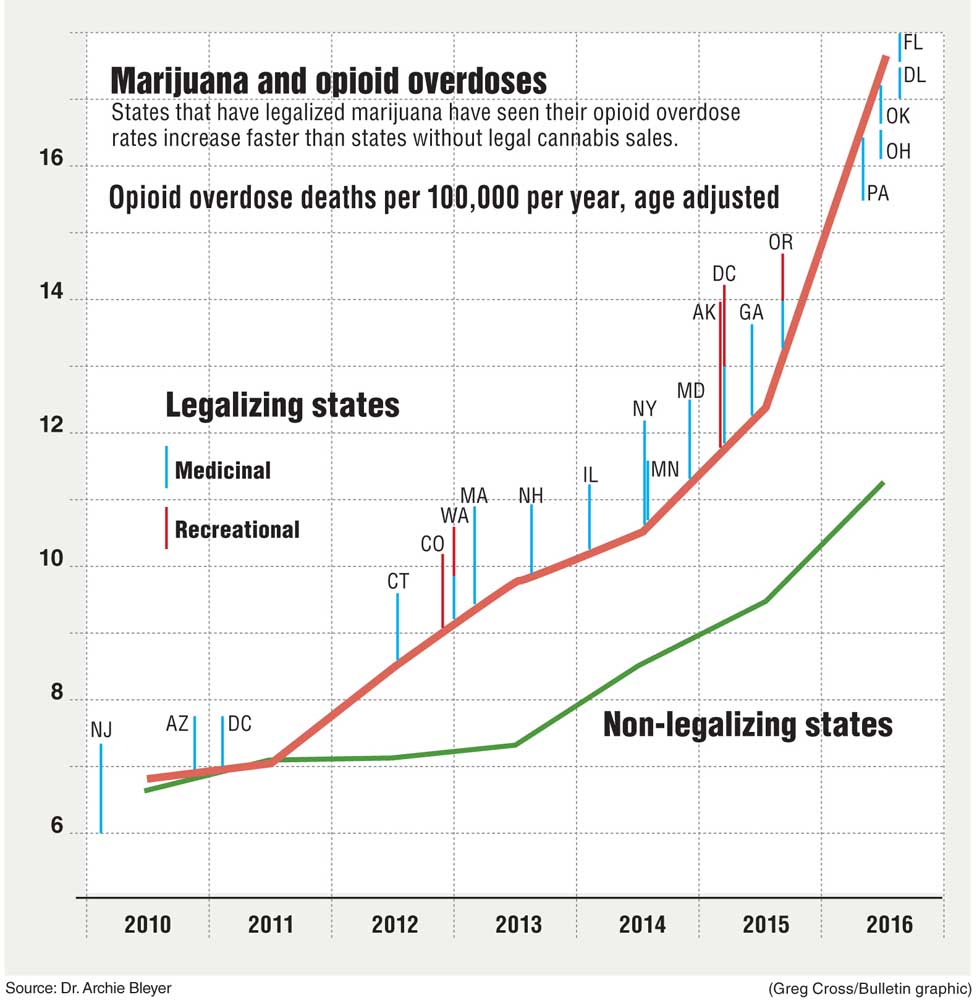

Writing in the medical journal JAMA Internal Medicine, Dr. Archie Bleyer, a retired pediatric oncologist from Bend, and Brian Barnes, a behavioral health and addiction specialist from Portland, compared opioid overdose rates in states that legalized medical or recreational marijuana with those of states that have not. They found that overdose rates were comparable in 2010, but over the ensuing years grew faster in states that had legalized cannabis.

The analysis has some methodological flaws, as pointed out by researchers who had identified the opposite trend. The authors treated states as having legalized marijuana for the entire 2010 to 2016 study period regardless of when they actually implemented their cannabis laws.

Prompted by that criticism, the authors redid their analysis to fix the statistical flaw.

“It came to an even stronger conclusion,” Bleyer said.

Bleyer and Barnes found that by 2016, legalizing states had 55 percent higher overdose death rates than states that had not legalized.

Their analysis was one of the first to reach that conclusion, as most of the earlier studies have found the opposite. In 2014, researchers led by Dr. Marcus Bachhuber at the University of Pennsylvania found that, between 1999 and 2010, states with medical cannabis laws had 25 percent lower overdose rates. Another study published earlier this year found states that legalized medical marijuana have 5.9 percent lower opioid prescribing rates, and those that allow recreational use, 6.4 percent lower than states that did not.

Trending

Bachhuber’s study in particular had many advocates calling for more states to pass medical marijuana laws. But some addiction experts cautioned that marijuana policy was getting ahead of the science. None of the study designs allowed researchers to draw causal connections between marijuana and overdose rates. And overdose rates continued to climb even in states that legalized marijuana, just not as fast.

When researchers with the Rand Corporation redid the Bachhuber study earlier this year and extended the data for another three years, they found the impact on overdose rates had disappeared. That could be because, in later years, some states legalized medical marijuana but didn’t make it easy for residents to buy it. Lumping all legalization states together without regard for differences in their laws could be skewing the results, said Mireille Jacobson, a health economist at the University of Southern California and co-author of the Rand study.

“California, Oregon, Colorado look very different from other states where there’s not the possibility of actually buying marijuana,” she said. “It’s a very heterogeneous group.”

Jacobson said that, while cannabis may help chronic pain patients reduce the amount of prescription opioids needed to control their pain, increasing access isn’t likely to make a large dent in overdose rates.

“You can’t ignore that, but at the same time I don’t think it’s the solution to the opioid epidemic,” she said. “I really think that’s a very small piece of the puzzle.”

Bachhuber said it’s difficult to parse out the impact legalized cannabis is having on overdose rates from other efforts to address the epidemic. And federal prohibitions on marijuana research have stymied research into how cannabis might affect chronic pain or addiction.

But patient surveys show that cannabis may help reduce the amount of prescription opioids needed to control pain and could help those with heroin addiction moderate withdrawal symptoms or ease the transition to addiction medications such as methadone or buprenorphine.

The conflicting studies may also reflect a shift in the overdose crisis over time.

“The dynamics of the opioid epidemic have changed,” Bachhuber said. “It’s gone from mainly prescription opioids in the era that I looked at, to more heroin and fentanyl, and fentanyl analogs more recently.”

That could explain why earlier studies found a positive impact where later studies did not.

“The most likely explanation is it takes time to play out,” Bleyer said. “These are cultural shifts, and it takes time for a state and its residents to adapt.”

Bleyer and Barnes believe that marijuana can have both benefits and drawbacks for individuals with opioid addictions. It may help with withdrawal symptoms, allowing people to reduce their opioid use.

“It could also be, and these data suggest, that it could be a gateway drug and could get you into the problem of harder drug addiction,” Bleyer said.

They also cautioned about treating an addiction to one psychoactive substance with another.

“It’s not addressing the behaviors that go along with the substance use disorder,” Barnes said. “By using marijuana, they use less opiates, and their tolerance for opiates goes down. Then they have a bad day, relapse to the level that they were using and overdose because they’re not used to using that much.”

In combination with reducing opiate use, he said, people need behavioral supports to build skills for dealing with anxiety and stress of life.

Oregon legalized medical marijuana in 1999, and recreational sales began in 2015. The state was the only state to see a drop in opioid overdose rates from 2010 to 2015. Bleyer now fears that progress will be reversed.

“We need to worry about it becoming more of a problem and losing our advantage of having been able to keep the death rates from climbing,” Bleyer said. “I think we’re still in trouble. We’re at risk.”

— Reporter: 541-633-2162, mhawryluk@bendbulletin.com