St. Charles removes gender from patient ID wristbands

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, November 13, 2018

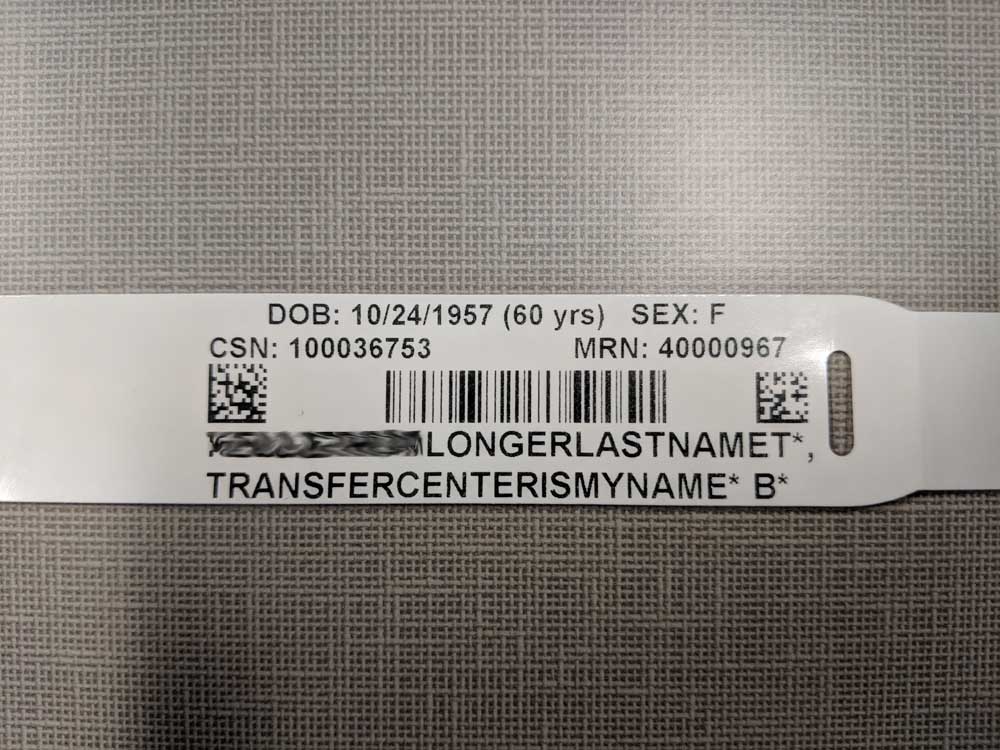

- Old patient ID bracelets at St. Charles hospitals indicated gender. (Submitted photo)

Last month, the St. Charles Health System made a small change that represented a huge difference for its transgender patients: It removed the gender designation from patient identification bracelets.

“It was something that everybody felt had to be on there because it was always on there,” said Rebecca Scrafford, a psychologist at St. Charles who was involved in recommending the change. “It’s providing no benefit, but it’s causing harm.”

The ID bracelet is designed to provide caregivers an easy way to identify patients based on two distinct identifiers. But staff generally check the patient’s name and date of birth, not gender.

Until recently, the hospital’s record system did not distinguish between sex assigned at birth, legal gender and gender identity. The ID bracelet had been showing the patient’s legal name and sex assigned at birth.

“For a lot of those patients, that didn’t match, and that was distressing for our patients,” Scrafford said. “This is one little baby step in providing affirming care that is probably the first visible sign of many efforts that are underway at St. Charles and communitywide.”

Last year the hospital held a transgender health care training event for providers, and this year convened an internal sexual orientation and gender identity work group to guide initiatives around welcoming transgender patients. Meanwhile, the new Central Oregon Transgender Healthcare Coalition held its first meeting last month, establishing a goal of expanding capacity for transgender health in the community.

The hospital has now trained its staff about when and how to ask about gender identity, and how to record that information in the patient’s record.

“You can have the nicest provider in the world, but if the person at the front desk says the wrong name and gender, it’s not going to be the greatest experience,” Scrafford said.

Surveys show many transgender people have had negative experiences interacting with the health care system and nearly half say they avoid medical care because of it.

“Patients will access care first and foremost if they feel safe accessing care,” said Dr. Christina Milano, a professor of family medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, and an expert in transgender health issues. “Unfortunately, transgender and gender diverse individuals have a long history experiencing things like discrimination or inappropriate questions and comments regarding their gender when accessing health care.”

Limitations in electronic health records, she says, often mean printed labels or ID bracelets don’t align with a patient’s gender identity.

“A wristband that a patient is wearing in a hospital during a critical time, a scary hospital admission, that’s something that they’re staring at 24/7 during their waking hours,” Milano said. “So having that being gender affirming by either having the correct gender or having no gender marker — so avoiding the risk of the wrong gender marker — is a big positive.”

But the limitations of the record system often mean transgender patients must sacrifice their privacy to get things corrected.

“I’ve had to publicly out myself many times,” said Rob Landis, a transgender man from Prineville and a board member of the Human Dignity Coalition. “If I was any other transgender person, I could have gotten very offended and hurt by that.”

Landis recounted a visit to one clinic where the woman checking him in for his appointment burst out laughing when she pulled up his records.

“That’s so weird. There’s an F here on the screen where there should be an M,” he recalls her saying. “Yeah, it’s not really funny because I’m transgender.”

Another time he had to explain why he was coming for an appointment with a gynecologist.

“I had to out myself again, to say I had some female parts that needed to be removed,” he said.

Still Landis says he has seen tremendous change in Central Oregon. When he started his transition six year ago, he had to research which providers locally were familiar with transgender health issues and if offices would treat him with respect.

“I thought Central Oregon was like it’s own little island that has been kept from the real world,” Landis said. “But doing some research, there are a lot of providers out there locally. I don’t have to go to Portland.”

The Human Dignity Coalition has served as a clearinghouse for transgender individuals seeking health providers, sharing word-of-mouth reviews of which doctors were knowledgeable and accommodating. It also holds training sessions for providers and staff on transgender issues.

Coalition president Jamie Bowman has two transgender daughters and tries to pre-empt problems by informing the front desk when she checks in that her child’s legal name isn’t the name she now uses.

“I just hope that the waiting room full of parents and other children didn’t hear, and then hope and cross my fingers that when the nurse comes to the door to call my child, she would call the right name,” Bowman said. “And just last week, they didn’t.”

Two years ago, her daughter received an ID bracelet with the wrong gender at the emergency room at St. Charles Redmond.

“I just looked at it and sighed. And then the admit person came back with a different bracelet, took the M off, and put an F on instead,” she said. “Even that little bitty thing, it just made all the difference to my child.”

There are an estimated 1.4 million transgender people in the United States, representing about 0.6 percent of the population, although those numbers may represent an undercount. Scrafford said that’s more than the 1.25 million with Type 1 diabetes. Yet health care organizations are much more attuned to the needs of those with diabetes than of transgender patients.

That’s changing, but slowly. Electronic health records systems are starting to switch from a binary male or female designation for gender to more nuanced options. The Epic electronic health record system, which St. Charles implemented earlier this year, allows organizations to distinguish between sex at birth, legal gender and gender identity. A fourth field allows patients to designate a chosen name.

Epic recently concluded a massive review of its record system to look at every place gender or name were identified, to determine the most appropriate designation to be used there.

“Were we using it to signify biology? Were we using it understand how to address the patient? Were we using it to communicate with an insurance company?” said Janet Campbell, vice president of research and development relations for Epic.

That functionality now exists in the software used by nearly all of its clients, but the expanded gender identity categories can be disabled. Campbell estimates only about a third of their clients use the full functionality.

Bowman said the change in wristbands and other moves by St. Charles to make transgender patients feel welcome could have much broader implications. As the region’s largest employer, the hospital could serve as a catalyst for the rest of the community, particularly in the more rural regions of Central Oregon.

“Places like Madras and Prineville are just decades behind. It seems like traveling back in time the further out of Bend you go,” Bowman said. “Just having those plans, where it’s a consistent health care system, a consistent employer, a consistent voice in all of those communities, it’s going to be so much more important in Madras and Prineville.”

— Reporter: 541-633-2162, mhawryluk@bendbulletin.com