The lure and fanaticism of steelhead fishing

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, November 14, 2018

- The lure and fanaticism of steelhead fishing

TELKWA, British Columbia — Steelhead are a form of oceangoing rainbow trout endemic to some rivers draining to the Pacific Ocean from North America and Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. They are also a metaphor for wonder and optimism.

The wonder speaks to the fish’s epic life cycle — a journey of hundreds of miles to the sea from its natal river, thousands of miles in the North Pacific feeding and growing, and hundreds of miles back home to spawn. Some fish return to the sea to complete the cycle again.

Trending

The optimism concerns their elusive nature, at least as far as anglers are concerned. Many steelhead anglers will log days and days — thousands of casts — with nary a nibble. The fish’s seeming lack of interest only heightens its appeal, since steelhead do not feed in most river systems and are believed to strike a fly from a territorial instinct. That, and the raw power of their take, which is positively addictive.

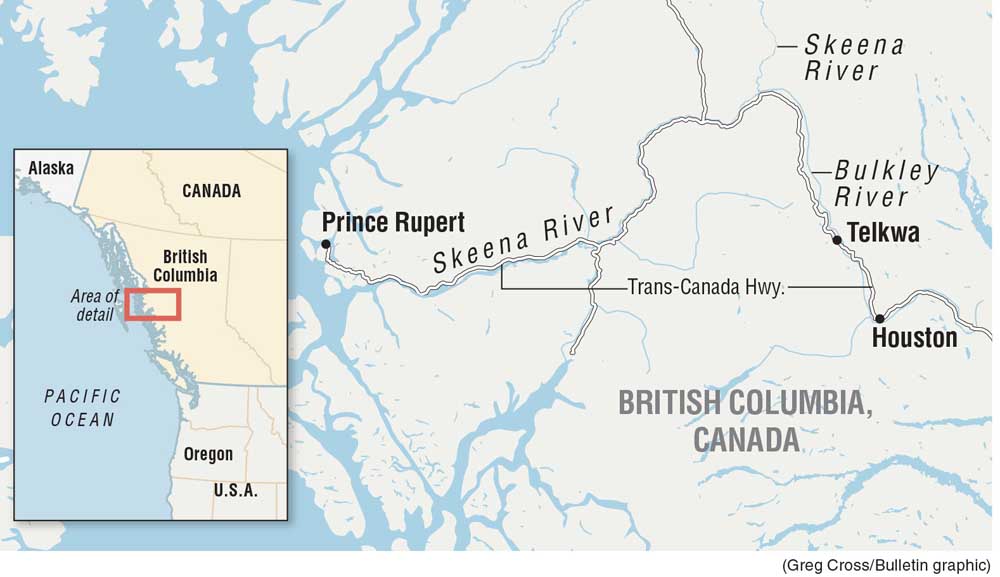

The Skeena River flows some 350 miles in a southwesterly direction from its headwaters in northwestern British Columbia to the Pacific near Prince Rupert. Along the way, it picks up tributaries that represent a “who’s who” of the world’s most celebrated steelhead fisheries — the Babine, the Bulkley/Morice, the Copper, the Kispiox, the Sustut.

The region’s identity is closely tied to its angling treasures; in the gateway town of Houston, a 60-foot fly rod graces Steelhead Park. Motels and campgrounds advertise, “Steelhead Fishermen Welcome.”

For any serious steelheader, the rivers of the Skeena drainage are Valhalla.

Fly fishers are a hopeful lot by nature; how else can you believe that pitching a bit of fur and feather into a vast river will yield a fish? Steelhead aficionados ratchet that optimism up to a near fanatical — if not masochistic — level.

While returns in much of the steelhead’s historic range are disturbingly low (with many populations at risk of extinction), the rivers of the Skeena drainage remain relatively healthy. Hence an angler’s odds for success increase.

Trending

“There are no hatcheries on the Skeena system, no dams, and abundant healthy spawning habitat,” noted Pete Soverel, founder and president of the Conservation Angler, which advocates wild anadromous fish populations. “This makes the rivers of the Skeena ideal for sustaining healthy wild steelhead populations.”

At a bend in the Morice River near the village of Houston, my fishing partner Mike Marcus suggested we anchor our raft. The crystalline water immediately before us flowed fast — too fast for fish to hold. But about 80 feet out was a jumble of rocks where the water briefly slowed.

“I bet there’s a fish there,” Marcus said, before inviting me to try my luck first.

I waded out and began casting slightly downstream, letting the fly swing toward shore with the current. Looking back upriver, I was struck by the setting — thick pine forests on both banks, and rugged snow-fringed mountains beyond, bifurcated by a thin line of morning mist. A few more casts and the fly — a purple Hobo Spey — swung just beyond the rocks. Almost on cue, my spey rod jolted as line screamed off the reel. A steelhead soon launched from the river, a silver missile that was speeding downstream.

Some anglers will spend more than $7,000 a week to visit fishing lodges on the Skeena’s rivers. That was not in our budget; but the Bulkley and Morice (which is essentially the upper portion of the Bulkley) have enough public access points to make a do-it-yourself trip possible. After much planning — a rented house in Telkwa, Google Earth maps of the river and hours of tying flies — our group of five loaded two trucks with rafts and supplies and headed the nearly 1,000 miles north from Portland.

My one previous trip to the Bulkley, in 2001, had been a disaster. Heavy rain had transformed the river’s generally clear waters into chocolate milk, rendering it almost unfishable. Rivers going out of shape is a constant threat in this wet part of the world. My companion and I hooked two steelhead that week.

There was little rain in the forecast for 2018’s mid-September week — prime time for fish returns — and we were heartened to arrive at the Walcott bridge boat launch on day one to find clear water.

Over the next five days, we floated four different sections of the Bulkley/Morice, rising before dawn and returning to our domicile after dark. We ran our own shuttles, leaving one vehicle at the takeout point so we could return to retrieve the second truck from the put-in. Then we returned to the takeout to retrieve our rafts.

One starting point on the Morice lacked a formal boat launch, requiring us to carry our rafts down a steep bank to the river — no small feat for our aging crew. This was a buddy’s 60th birthday celebration. Fishing was difficult, thanks to colder than usual water temperatures. We slowly cracked the code. On the last two days, Marcus and I each hooked nine fish, a season’s worth of fish on our home rivers.

On the long ride home, we contacted the owner of the Telkwa house about its availability in 2019. The Bulkley excursion may become an annual pilgrimage.