A drive to Antelope and Shaniko offers a glimpse of history

Published 12:00 am Sunday, November 18, 2018

- A drive to Antelope and Shaniko offers a glimpse of history

“It’s so quiet here. I love it,” my sister, Heather, whispered as we walked through Antelope on a recent cool morning.

Among the rustle of crispy-leaved Cottonwoods and an occasional breeze, there was an empty town with an eerie stillness, much like the rest of southern Wasco County.

Antelope has never been particularly populated — its population has hovered around 45 since the mid-1980s; it and its neighboring city, Shaniko, are vast and beautiful, as well as sites to some of Oregon’s offbeat historical moments.

A trip to southern Wasco County during the offseason may yield desolate results in terms of man-made attractions. But the landscape alone is a feast for the eyes.

Day-tripping is one of my favorite pastimes. As a kid, our family would regularly go on day trips. Mom would fill the cooler with sandwich makings, and Dad would chart out a course in the red Gazetteer. Then, we were off. Mom, Dad, Heather and I would pile into the Bronco (gas was cheaper then) and set off to explore a new pocket of Oregon.

The destination was rarely the focus of these trips. The excursion focused on the landscapes, small towns and waysides along the way. It was about the history found in places where the ravages of time are evident wherever you turn.

Colorful history

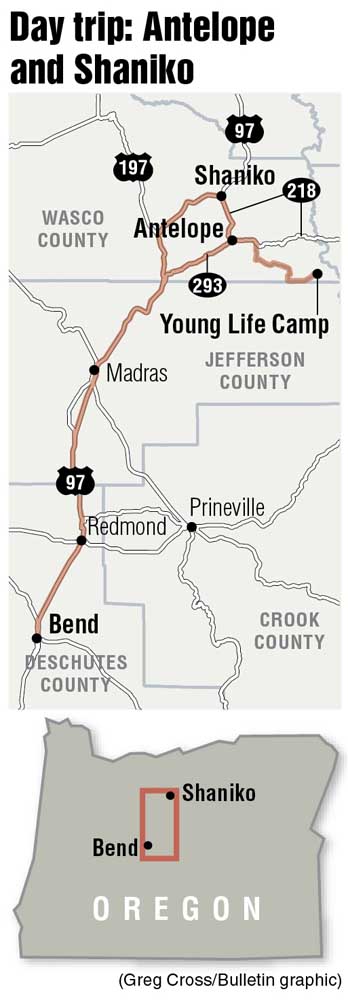

Antelope, a destination our family never fully explored, is about 75 miles northeast of Bend. After heading north on U.S. Highway 97 for about 61 miles, we turned off for Antelope and were immediately plunged into a columnar basalt canyon.

The tall, dark walls absorbed the light as we twisted along Antelope Creek. A short distance later, the landscape returned to farmland. Barns and houses dotted the area and the occasional tractor crossing sign added that extra dash of country life.

Antelope is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it kind of town. Antelope Highway bypasses the city and doesn’t look like much at 55 mph. The town was settled in 1863 by Howard Maupin. Later, it established a stage stop on the road between The Dalles and Canyon City (near John Day).

In 1892, the unincorporated town saw a boom, mostly due to traffic from cattlemen, sheep ranchers and miners. It offered a lively social life complete with boardwalks, three livery stables, gaslights, four hotels, a jail, a community center called Tammany Hall and seven saloons.

Antelope incorporated in 1898 with a population of 170. The same year, a fire destroyed most of the business district. Since, the town never fully recovered. A few buildings remain from the early days: a community church and the Ancient Order of the United Workmen Hall.

The recently painted hall hosts a museum about the area, highlighting in particular the four-year saga (1981-85) of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and his religious followers relocating their world headquarters to Muddy Ranch.

There was a sign taped to a window that caught my eye driving in.

The words typed on computer paper said, “Wild Wild Country.” Upon closer inspection, there were also two color posters with the images showing a crowd of people clad in red: “As seen in, ‘Wild Wild Country’” was written in script at the top. The museum was closed the day I visited. According to the museum’s Facebook page, it’s open occasional weekends during the summer.

If you want a detailed account of what happened in Antelope during that time, watch “Wild Wild Country,” Netflix’s Emmy-award-winning documentary.

Here’s a synopsis: An Indian man who went by Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh founded a religious group who then moved their world headquarters to the Muddy Ranch outside of Antelope in 1981.

Their intent was to be a self-sustaining community and be able to practice their religion freely. Tensions between the Synassans (as the followers were called) and the locals began early and progressively worsened as the group’s numbers soared.

Bhagwan’s chief secretary, Ma Anand Sheela, gained control over the affairs of Rancho Rajneesh (as the Muddy Ranch was called) and began setting in motion a series of events that ended with Antelope being renamed Rajneeshpuram, the poisoning of county officials in The Dalles, the extradition of the Bhagwan, Sheela fleeing to Europe and the Synassan numbers dissipating.

There is a small plaque commemorating the locals in their efforts to resist the “invasion and occupation” at the bottom of the flagpole at the post office.

Other than that marker, there is no remnant of the ordeal in town.

Back at the Ranch

If you want to see where it all happened, you can still drive out to the Ranch, which is now private property owned by the Washington Family Ranch — A Young Life Camp. The Washington family bought it in the 1990s. After trying to turn the land into a resort, the family let Young Life run its youth ministry camp out of it.

The land that once housed thousands of Synassans has been renovated and repurposed for Young Life. The road to the ranch is a county road that eventually leads to the Painted Hills.

Driving between working cattle ranches and juniper forests, we spotted a lone coyote, a small herd of deer and about a million Robins.

When we reached the top of a hill, the landscape below opened up to ancient rolling hills and moody clouds above them.

I let out a few “wows.” I now realize why people want to live here. It’s remoteness is invigorating, and there is an energy to the hills.

We had to turn around when we got to the Ranch. We stopped to regroup and check the map (no cell service). We hadn’t been stopped more than 5 minutes when a pleasant woman from Young Life drove up to see if we needed help.

She told us the best way was back the way we came. We listened.

Not dead yet

Shaniko has been called “Oregon’s Best Ghost Town,” but it is not as lifeless as one might think.

The town, once the largest inland producer of wool in the world, has been somewhat restored to appear as it may have during its heyday.

If you visit in the off season, the town is mostly shut down and desolate. Many of the shops are open seasonally, gas stations are closed, buildings are plastered with “no gas” signs, museums are shuttered and you won’t find many humans walking the streets (though there was a friendly cat who followed us around).

Information signs scattered around the old city hall building inform visitors of Shaniko’s past and the people that brought it into existence. You can walk into the old, one-room jail for a peak. Signs indicate people are working to restore it.

One constant, Sage Museum, is open year-round and open daily. It holds a plethora of in-depth historical information such as the “first intercity bus in the United States,” which ran from Shaniko to Bend in 1905. There’s history about the founding of the town by German settler August Scherneckau and today’s restoration efforts.

We were reminded of the seasonality of the town with a glance at the visitors book, which offered an apology of all the other businesses in town: “Sorry everything is closed! Come back May-October.”

The General Store was open and is the only place during the winter to get any food in the area — mostly snacks — and antiques. The narrow few aisles that extend to a lean-to on the side of the building were filled with trinkets.

There was a strange looking green building across the highway from the store, the Shaniko School.

Now used for events and a town library, one room of the two-room school houses a toy and game museum.

When we walked over to it, we expected the same shuttered doors as the rest of the town, but to our surprise the door was slightly ajar and a sandwich board outside stated its winter hours. “First weekend Oct., Nov., Dec., (etc.).”

A woman welcomed us at the entrance and quickly ran through the history of the building as well as some of the museum’s collection: Monopoly games from around the world, a 1940 “Dick and Jane” book, a few original desks from the school and part of a wooden 1918 pipe that provided water to the students.

The room still features its original wood and coal burning stove that was the only source of heat.

“Works about as well as what I have right now,” the woman said with a laugh.

A mountain identifier wayside on the way out of town indicated that, presumably, on a clear day you can see Mt. Rainer along with several other peaks in the Cascades.

Like I said at the start, these day-trips are rarely about the destination. They’re about the road along the way, history, landscapes and the chance to discover something new.

— Reporter: 541-383-0304, mwhittle@bendbulletin.com