OSU climate change report a mixed bag for Central Oregon forests

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, November 28, 2018

- OSU climate change report a mixed bag for Central Oregon forests

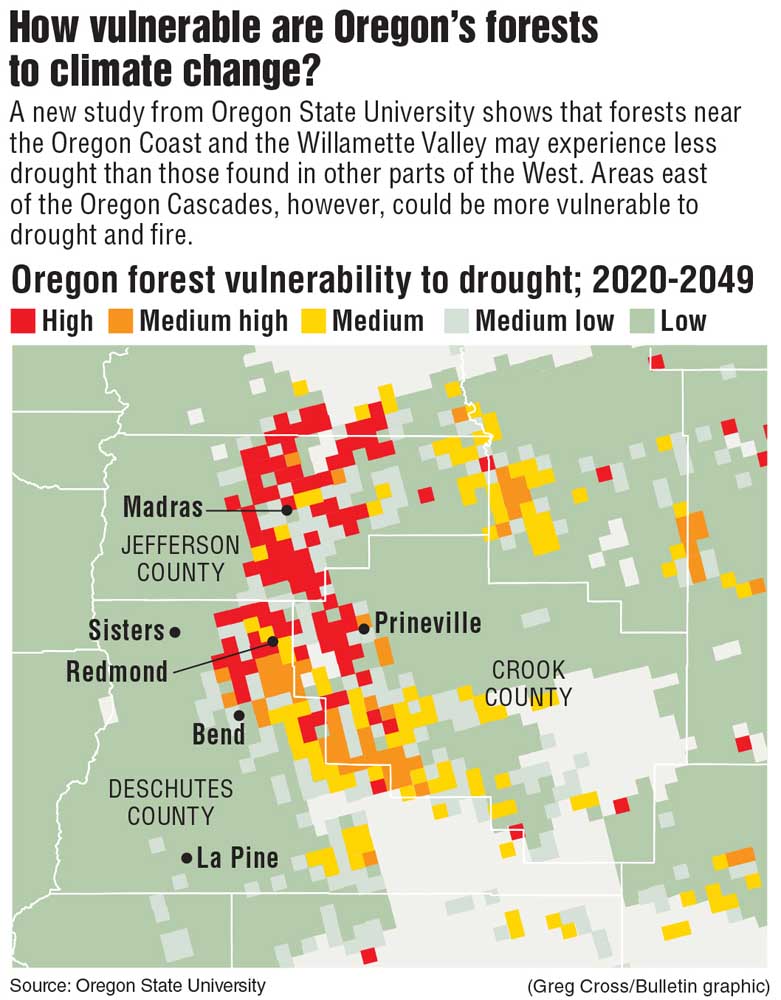

A new report produced by Oregon State University paints a surprisingly rosy picture for many Pacific Northwest forests in the face of climate change, but the impact on forests east of the Cascades is much more of a mixed bag.

The results of the study, published in the industry publication Global Change Biology earlier in November, demonstrate that the effects of drought and larger fires driven by climate change will not be spread equally across forests in the Western United States over the next three decades.

Trending

Instead, the study shows that cooler, damper forests dominated by coastal Douglas fir, hemlock and redwoods may see less drought and fire than other Western forests as the climate warms.

“The 30,000-foot view is that we’re probably in the sweet spot in the Pacific Northwest,” said Bev Law, an OSU professor and one of the authors of the study. “We’re not going to be as bad off as everybody else.”

However, forests dominated by other types of trees, including the inland Douglas firs, lodgepole pines and ponderosa pines found in many Central Oregon forests, may not be spared the effects of climate change, according to the study. Consequently, Law said, the map of fire and drought vulnerability east of the Oregon Cascades is a patchwork of high- and low-susceptibility areas.

“It looks really spotty on the east side,” she said.

In Central Oregon and throughout much of the West, human-caused climate change has been linked to prolonged droughts and hotter, drier and longer fire seasons, raising concerns about the future of forests in a warmer world. Law said trees like ponderosa pines and Douglas firs, staples of the Deschutes and the Ochoco national forests, may get pushed out of their current range if the region endures prolonged droughts.

The report was intended in part to help scientists and land managers better understand those impacts in various regions, according to OSU.

Trending

Law added that work on the study, which was funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Energy, began about five years ago. Researchers used carbon data and other inputs to map forested areas across the Western United States, dividing them into 13 varieties based on the dominant type of tree in each area.

“It’s a big monster of a model,” Law said.

From there, Law said researchers used models to simulate the impacts of climate change through 2049. Law said most climate change simulations run through the end of the 21st century, but added that the report wanted to focus on a shorter time horizon, which would provide more accurate data. Researchers used two main models: one that averaged a mix of different climate models, and one that provided a more extreme version of shifts in climate.

The report showed that forests in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains and areas across the Mountain West, including parts of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, can expect to see significant impacts from climate change in both scenarios.

On the other hand, forests in most of the coastal and western Cascades in Oregon and Washington, as well as portions of northern Idaho and Montana, may be spared the worst of the fire and drought.

In Oregon, the model predicts higher-than-average drought conditions over the next 30 years in forested areas north and east of Bend, as well as parts of Grant, Harney and Umatilla counties. Much of southwest Oregon, along with a narrow band in north-central Oregon and pockets to the east of Bend, may be more vulnerable than average to wildfires in the coming years, according to the study.

Law said much of the regional variance comes down to questions about future rain and snowfall, along with variance within the climate and the tree canopy across the eastern half of the state.

In the Ochoco National Forest, which spans 850,000 acres to the east of Prineville, ponderosa pines dominate, though a number of inland Douglas firs, grand firs, junipers and western larch are mixed in, according to Rob Rawlings, silviculturist for the national forest. Rawlings said the forest tends to be lower in elevation and drier than the Deschutes, typically receiving between 15 and 33 inches of precipitation annually.

Because of that, drought is a significant factor, one that would impact Douglas firs and grand firs first, Rawlings said. Unlike coastal Douglas firs, which have adapted to a wetter, cooler climate, the firs in the Ochoco National Forest are used to seeking out water, developing large root systems to soak up the limited water in the forest. Still, Law said firs are less drought-tolerant than juniper and ponderosa pines, and may suffer if the region dries out in the future.

“On the east side, (the roots) just might not be enough,” Law said.

— Reporter: 541-617-7818, shamway@bendbulletin.com