Doctors explore link between childhood infections, mental illness

Published 12:00 am Sunday, December 16, 2018

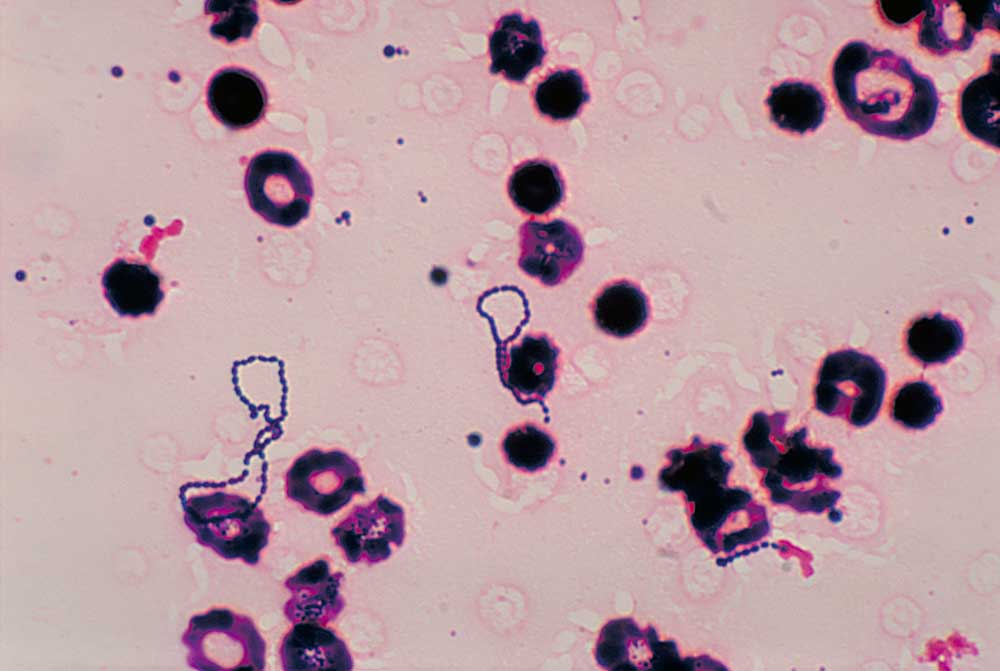

- Photomicrograph of streptococcus bacteria in a blood culture. (Centers for Disease Control/Submitted photo)

Lori Goldsmith used to call her daughter Laid-back Layla. She was so easy going, so friendly and outgoing, nothing seemed to bother her much.

Then one December morning, Layla woke up, and everything was different.

Trending

Without warning, the “kind of messy” kindergartener couldn’t tolerate anything out of order. Her outgoing, friendly personality turned aggressive and she started getting into fights at school. Her mother, a licensed marriage and family therapist in Bend, was stunned by the sudden change in her daughter. Her teacher called home to ask what had happened.

Layla began obsessing about her cubby hole at school, unable to leave it until everything was neatly organized. She got upset if her classmates didn’t tidy up the play kitchen well enough. At home, her clothes had to be in precise order, her shoes perfectly straight. She couldn’t stand it if the door to her room was ajar.

“We couldn’t figure out what was going on,” Goldsmith said. “Typically, you don’t see things happen like that overnight.”

The school counselor suggested Layla be evaluated for autism. The pediatrician referred her to a psychiatrist.

As they tried to get to the bottom of her abrupt symptoms, Layla started stuttering and moving her head in a strange awkward manner.

Then her pediatrician called with an answer they hadn’t expected. It’s possible that all of her behavioral changes — the anxiety, the obsessive compulsiveness — were due to not to a psychiatric problem, but an infection.

Trending

Evidence is mounting to support the idea that common childhood infections such as strep can trigger an immune response attacking the brain, causing the abrupt onset of behavioral changes or mental illness.

Known as pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome, or PANS, it is a scenario that could be affecting as many as one out of every 200 children. Yet, few doctors recognize the condition or know how to treat it. Some deny the condition even exists.

That’s left the parents of the affected children to push for greater recognition, advocate for laws to require insurance coverage and trade information about which doctors will help them diagnose and treat it.

PANS is an umbrella term representing a variety of disease mechanisms that can cause the sudden onset of neurological or psychiatric symptoms. In the mid 1990s, Dr. Sue Swedo, a researcher with the National Institute of Mental Health, described how children with streptococcus infections, the bacteria behind strep throat, could experience a sudden onset of obsessive compulsive disorder or severe eating restrictions, often accompanied with facial tics.

It’s unclear why these infections do not seem to affect adults in the same way.

She called the condition pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections, or PANDAS, describing a process similar to that of rheumatic fever.

Strep throat is generally treated with antibiotics to prevent rheumatic fever, which can damage other organs in the body, notably the heart. The syndrome identified by Swedo could represent rheumatic fever of the brain.

The notion that strep infections were causing mental health issues was controversial. Strep is so common, it’s difficult to find a child who hasn’t been infected.

“None of these kids were being treated because they were still arguing over the cause,” said Dr. Jennifer Frankovich, a pediatric rheumatologist and director of a clinic at Stanford University that studies the syndrome.

To bypass the debate over strep, researchers developed the PANS diagnosis, allowing for multiple possible sources of infection that cause a sudden mental deterioration.

“The children that come to our clinic are doing fine in school, going to their after-school activities, well-behaved at home. And then all of a sudden overnight there is this very dramatic change in the child, where they develop very extreme OCD that can often be paralyzing,” she said.

Kids suddenly can’t leave their homes, they develop severe anxiety and sensory disturbances. Sounds become louder than they are, lights brighter. Some taste things that aren’t there.

“Some of these sensory disturbances are so extreme, it can look like hallucinations or a psychosis,” Frankovich said.

Some become suicidal or even homicidal. Many develop extreme episodes of rage. They can regress in motor function, their handwriting deteriorates. Some children will start wetting their pants or having frequent urination. Others will lose their ability to feed themselves or brush their teeth. School-age children can start to talk and act like toddlers.

Many develop verbal or facial tics.

‘When is it going to end?’

The change is so abrupt many parents can point to the exact day their child developed symptoms. For Sarah Lemley’s daughter, Dylan, it was just after she completed third grade in 2016 and about two weeks after an illness which they now suspect may have been strep.

“She went to bed one night the same kid we’d known for eight years and she woke up the next morning severely debilitated, the highest level of anxiety I’d ever seen in anyone.”

Dylan couldn’t leave the house, and then developed an obsessive compulsive disorder. She became terrified of choking, and soon could eat only soft foods. She developed a vocal tic, making a certain noise over and over.

“She would make comments to me, ‘Can I make it stop? Can I make it go away, When is it going to end?’” Lemley said. “She recognized that something was very wrong with her body.”

Her handwriting deteriorated from a beautiful cursive script to that of a kindergartener.

Lemley spent the summer trying to coax Dylan out of their home, in hopes of getting her back to school in the fall, taking baby steps until she could enter a grocery store and be among people.

The Lemleys waited months to get an appointment with a child psychiatrist in Bend. After Lemley told Dr. Merritt Schader their story and they got Dylan in to see her for 15 minutes, Schader told them it was a textbook case of PANS.

Schader had studied at Stanford and remembered a presentation from one of the doctors at the PANS clinic.

“She showed us the change over time with these kids, how they were able to draw and they went from these beautiful drawings to those of a 3-year-old, all associated with strep,” Schader said.

While Schader was familiar with PANS, she wasn’t up to speed with treatment protocols. The Stanford clinic couldn’t help either. Because of the high demand, the clinic only sees patients from within a 90-mile radius.

The Lemleys eventually found their way to Amy Smith, a nurse practitioner in Mountain View, California, who started specializing in PANS treatment after her son developed the condition. By that time, Dylan had already been taking anti-inflammatories, and the Lemleys had started to see progress. After Dylan tested positive for strep antibodies, Smith suggested additional treatments. Now, after months of antibiotics and weekly counseling, the anxiety and obsessive compulsiveness have faded. Dylan, now 10, has expanded her diet and her episodes of rage occur less frequently. The Lemleys made the difficult choice to move from Bend to Portland, where care was more easily accessible.

“It’s been a traumatic 16 months for us,” Lemley said. “We literally felt like we went through hell for three or four months, and finally, she’s in a place where she’s thriving.”

Lemley has since co-founded the Northwest PANDAS/PANS Network to help raise awareness and connect parents in Oregon, Washington and Idaho with diagnosis and treatment options. The group is working closely with OCD Oregon, a local affiliate of the International OCD Foundation to combat the notion that PANS is a rare disease.

Swedo estimated that 25 percent of children with OCD could have PANS that hasn’t been diagnosed.

“That’s the big fear,” Lemley said. “Are these kids being diagnosed with ADHD, ADD, autism or some other mental health issue, when they really have an underlying infection that’s causing those mental health symptoms?”

Layla’s pediatrician was willing to help but admitted she knew little about the condition or how to address it. Lemley referred the Goldsmiths to a naturopath in Portland who had more experience with PANS. A battery of blood tests revealed Layla had a mycoplasma infection, the bacteria that causes walking pneumonia. Now six months later, after taking antibiotics continuously, her symptoms have largely faded away.

“Her OCD is gone,” Goldsmith said. “I almost have my Layla back.”

In January, Layla, now 7, will scale back the antibiotics to just two days a week. She is slowly working her way back to resuming the life she had before her symptoms appeared, balancing the benefits of more activities against the risk of being exposed to other infections that could cause her symptoms to flare again.

Health care disconnect

Children with PANS suffer from a longstanding split between physical and mental health. Pediatricians or emergency room doctors see psychiatric symptoms and refer families to a psychiatrist. Psychiatrists may be more open to a physical trigger for mental health issues and generally don’t deal with infectious disease or immune disorders.

“There are a lot of thoughtful clinicians that believe this real and that want to do something to help these kids, but they just simply can’t because there’s no venue for treating them,” Frankovich said. “Even in my own hospital, they can’t admit kids with psychiatric disease because we don’t have nurses trained to manage someone with psychosis, that’s a flight risk or aggressive.”

Even the most ardent supporters of PANS admit they can’t prove that strep or other infections are causing the psychiatric symptoms. The suddenness with which the condition arrives suggests that is the case, Frankovich said, as most immune disorders tend to build up slowly.

Researchers such as Frankovich believe that PANS stems from a combination of genetics and an overactive immune system.

“We think the infection is playing a role in tipping the kid over,” she says.

Doctors lack a go-to laboratory or imaging test to definitively diagnose PANS.

Treatment is similarly challenging. While providers specializing in PANS research have published treatment guidelines, the recommended treatments don’t always work.

A significant portion of the medical establishment, however, doesn’t believe PANS is real. Critics counter that children might have acute flare-ups of underlying psychiatric or neurological conditions, but there’s no proof that infections are the trigger. In 2016, Dr. Stanford Shulman, an infectious disease specialist at Northwestern University in Chicago, wrote in the journal Pediatric Annals that he and many other experts on strep infections believe PANDAS “has not been proven to be a specific entity” and that “the great preponderance of scientific evidence on this topic has been nonsupportive.” Those non-believers argue that patients with sudden onset obsessive compulsive disorder should be treated with standard OCD therapies, rather than with antibiotics, antiinflammatory or immunologic medications.

This month, however, a large Danish epidemiological study published in JAMA Psychiatry threw more support behind the PANS diagnosis.

Researchers analyzed data from Denmark’s extensive health registry, allowing them to compare rates of mental illness in children who had been treated for an infection against those who had not. The study found that the risk of developing a mental illness was 80 percent higher in children who had been hospitalized for a severe infection, while children who had been treated with antibiotics outside the hospital had a 40 percent greater risk. It was unclear whether antibiotics themselves cause the increased risk or just signaled which children had an infection in the first place. For certain mental disorders, especially obsessive compulsive disorder, the study found an eight times higher risk with an infection than without.

In an accompanying editorial, Drs. Viviane Labrie and Lena Brundlin from the Centers for Neurodegenerative Sciences in Grand Rapids, Michigan, said the study “provides strong evidence that severe infections … place children and teenagers at greater risk for developing neuropsychiatric illness.” It was plausible, they wrote, that the increased risk observed in the study represented PANS or PANDAS.

Finding help

Faced with skepticism from hospitals and clinics, many parents now rely on naturopaths or nurse practitioners for treatment, overwhelming those few providers who specialize in PANS.

“I have a waiting list of almost 200 suffering, sick children that don’t know where to go,” Smith, the northern California nurse practitioner, said. “It kills me because I’m at maximum capacity.”

The controversy over PANS also affects insurance coverage. Many parents must appeal over and over again to get coverage for treatment, particularly for expensive infusions of antibodies that has been shown to be effective for the more difficult cases.

Debra Miller of Scappoose and her husband have spent thousands of dollars getting a PANS diagnosis for their 9-year-old son, Kamden. His rage episodes were so bad, their family had a set protocol: his older brother would take his younger brother and lock themselves in a bedroom until it was over.

After lab tests revealed multiple infections, he was treated with antibiotics and steroids. Smith has recommended the family pursue an antibody infusion. The Millers are now appealing their insurance company’s denial for the third time. At a cost of $15,000 to $20,000 per infusion, it’s something the Millers simply can’t afford.

“I want people to know how serious it is, and how dangerous it is if he doesn’t get the help he needs soon,” Miller said. “There is no other step to go to.”

The Northwest PANDAS/PANS Network is working with Rep. Shari Malstrom, D-Beaverton, to introduce legislation in Oregon that would build awareness about PANS and require insurance companies to cover treatment.

Smith and Frankovich said that while much remains to be learned about PANS, treatments are effective and they have seen many children make dramatic recoveries.

“I see kids every day who get better from PANS and PANDAS,” Smith said. “The key is early diagnosis.”

Frankovich agrees.

“When these kids are treated early, they have a very robust response and they turn around very quickly,” she said. “It’s more challenging when the kids have repeated deterioration over time. Then it becomes harder and harder to treat.”

The goal of the Stanford clinic is not only to treat patients but to uncover how to best diagnose the disease and find what interventions will work the best.

“I don’t think anyone in our clinic is comfortable with being on the frontier with this,” Frankovich said. “We all go home and have nightmares. Are we doing the right thing? But if we don’t do this, we are never going to learn.”

— Reporter: 541-633-2162, mhawryluk@bendbulletin.com