The history of the Skyliners

Published 12:00 am Saturday, January 19, 2019

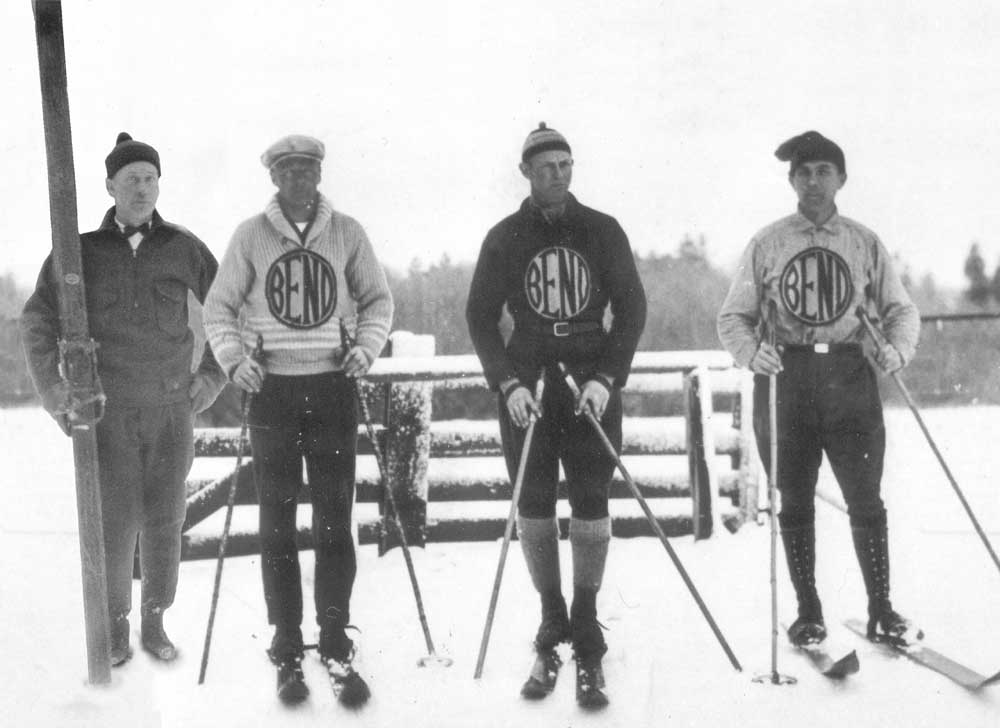

- Left to right: Chris Kostol, Nels Skjersaa, Nils Wulfsberg, Emil Nordeen. Photo courtesy of the Deschutes Historical Society.

Two Boys Are Reported Lost in High Cascades Near Bend; Snow Storm Hampers Rescue,” read the front-page news item in The Bend Bulletin on September 7, 1927. Amateur alpinists Henry Cramer and Guy Ferry of The Dalles had decided to climb the peaks of the Three Sisters range, embarking upon the North Sister on September 4. They made a successful climb and descent before setting out the following day for a second climb. As they ascended the mountain, a powerful winter storm moved into the area. After leaving camp to head up the slopes, Cramer and Ferry were never seen alive again.

“It is the opinion of local people who are acquainted with the rugged Three Sisters country that this area is even more dangerous in a storm than is the Mount Hood country, which claimed two lives last winter,” noted the Bend Bulletin reporter.

As news of the disappearance of Cramer and Ferry broke, several Pacific Northwest ski and mountaineering clubs arrived at Frog Camp, north of Sims Butte, to help look for the lost alpinists. In the evenings, members of the various organizations gathered around the campfires to trade gossip. Sometime during the two-week search, four Scandinavians— Chris Kostol, Nels Skjersaa, Nils Wulfsberg, and Emil Nordeen (pictured above)—decided Bend needed an outdoor club to train people how to be outdoor savvy. From this sad incident, Skyliners, Bend’s original ski club, was born.

Kostol, Skjersaa, and Nordeen had come to Bend in the late 1910s and early ’20s. After leaving Norway (Kostol and Skjersaa) and Sweden (Nordeen), they made their roundabout ways to Bend and started working for the Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Company and Shevlin-Hixon Company, which ran the two largest pine mills in the United States.

Toiling at the Bend mills, the men became fast friends. Their common Scandinavian heritage made them inseparable. Skiing and mountain climbing became important weekend activities for the three bachelors. When Wulfsberg arrived in Bend in 1927, he quickly joined the crew.

The three Norwegians and a Swede championed the Scandinavian traditions of friluftsliv, or outdoor living. Each of them had been active mountaineers and skiers long before they arrived in Central Oregon. Their friends called them the four musketeers of the mountains.

The musketeers founded Skyliners in December 1927, with the memorable name suggested by Paul Hosmer, Brooks-Scanlon’s newsletter editor. The Bend Bulletin congratulated the newly formed organization in an editorial on December 28, 1927: “Skyliners, Bend greets you. Go your varied ways realizing you are significantly named.”

As set forth in the newly adopted constitution, the club’s mission was “to promote all forms of outdoor recreation, especially hiking, camping, mountain climbing, skiing, snowshoeing, skating, and to assist in the acquisition of geological information concerning the Central Oregon country.”

The membership dues started off at a reasonable one dollar a year. In the first few months, the club membership reached 300 people.

Skyliners acted as a social leveler in the community. Members of the outdoor club came from all rungs of Bend society—millworkers, businessmen, and upper mill management. Compared to the many other fraternal and sororal organizations in Bend, Skyliners was an anomaly. The club was not gender specific. Men and women joined on an equal basis.

The founders understood the interplay between the fledgling outdoor organization and the business community. To the increasingly mobile tourist, Bend already had a well-established reputation for being a summer and fall destination. Skyliners would bring tourists to the area during the important winter season.

Skyliners’ first president, Carl Johnson, a respected member of Bend’s business community, lobbied the Bend Chamber of Commerce in April 1928. According to an article in The Bend Bulletin, he told the members, “Tourists can be kept in Bend at least three times as long if they are encouraged and are given accurate, definite information about side trips. . . . Keeping tourists in Bend longer means more money for the merchants.”

Skyliners’ first winter playground was established at McKenzie Pass, eight miles from Sisters, just east of the current snow gate. The two mills supplied all the lumber for the ski jump and warming hut. Even railroad executive Louis W. Hill of the Great Northern Railroad chipped in, saying by telegram, “I am pleased to advise you and members of Bend Skyliners club that use of my property for the club’s outdoor sports is entirely agreeable to me.”

Skiing and ski jumping were increasingly becoming winter sports to reckon with in the Pacific Northwest. Following the same path as Skyliners, Scandinavian millworkers all over the lumber- and snow-rich areas of California, Oregon, Idaho, and Washington founded ski clubs throughout the late 1920s and early ’30s.

At the end of January 1930, Skyliners announced plans to hold a ski tournament at their McKenzie Pass headquarters, the first such event in Central Oregon. Ski clubs in Oregon and Washington were invited to the mid-February tournament.

The day of the carnival, 2,000 spectators crowded the playground. Skyliners’ house committee had prepared coffee and food for the visitors. The lines around the mess tent were long throughout the day, and one unhappy individual, tired of waiting, reportedly started singing, “We’re in the army now.” Several visitors waiting in the same line promptly booed him out.

Skyliners’ first annual snow carnival was a certified success. The 25-mile cross-country ski race attracted six highly qualified competitors. Racing for Skyliners were Nordeen, Skjersaa, and Ole Amoth. Manfred Jacobson of McCloud, California, the two-time winner of the Fort Klamath race, Swedish Army ski champion “Walle” Nordquist, and Oliver Puckett of Fort Klamath also entered the race. Nordeen clinched first place, with Jacobson and Skjersaa taking second and third.

The sticky snow proved a challenge for the ski jumpers, throwing the contestants off balance. Skyliner John Ring squeezed out a 69-foot jump and won the competition, with Wesley Wygant of Hood River in second place and Skyliner Olaf Skjersaa (Nels’s brother) in third.

In 1931, Skyliners became one of the founding members of the Pacific Northwest Ski Association, and members of the Bend ski club quickly established themselves as major contenders in events throughout the Pacific Northwest. Nels Skjersaa was named to the all-American cross-country ski team by the National Ski Association. Emil Nordeen took home the Klamath trophy after winning the 42-mile Fort Klamath cross-country race twice, beating his countryman Manfred Jacobson in a thrilling duel. Chris Kostol became a respected official at many of the large ski meets around the Pacific Northwest.

Over the following years, Skyliners athletes competed against skiing greats such as Ole Tverdahl, Henry Sotvedt, and Leif Flak of the Seattle Ski Club; Hjalmar Hvam and John Elvrum of Cascade Ski Club in Portland; and Nordahl Kaldahl, Tom Mobraaten, and Hermod Bakke of Leavenworth Ski Club.

A diminishing snow pack and a wish to build a larger ski jump prompted Skyliners to relocate their home base in the mid-1930s. The Great Depression had also deepened, and as people cut back on expenses, travel to McKenzie Pass became a luxury few could afford.

Skyliners moved their winter playground to an area adjacent to the upper Tumalo Creek in 1936. The location was closer to town and provided a longer and steeper slope for ski jumping and skiing. The Forest Service and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) were heavily involved in the process of turning the area into a functional winter wonderland. Money came from the federal government in the form of work relief, allowing the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to build Skyliners Lodge, which has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1978 and used for a quarter of a century for conservation and outdoor education.

Ahead of the 10-year anniversary and the first competition at Skyliners’ new playground, Nordeen wrote a letter to the editor of The Bend Bulletin, published in December 1937.

“Ten years have now elapsed since the cornerstones were laid. The club often seemed on a none too solid foundation. It teetered and swayed dangerously, an impending crash often loomed in the background. But now the Skyliners playground is about to be completed.”

Skyliners inaugurated their Tumalo Creek headquarters in early 1938. It offered all the amenities needed for large competitions and featured classic Nordic skiing facilities: two ski jumps, one for adults and one for younger ski jumpers, as well as expansive cross-country trails.

European skiing, or alpine skiing, was an up-and-coming winter sport on the West Coast at that time. Adapting to changing trends, Skyliners included areas for both downhill and slalom skiing. By then, a new generation of ski jumpers and skiers had replaced the old guard. Olaf Skjersaa, Bert Hagen, Sam and Phil Peoples, Tom Larson, Cliff Blann, and Gene Gillis carried on the tradition of the ski club.

On February 27, 1938, Skyliners held its first tournament at their newly finished winter headquarters. The meet attracted athletes from clubs all over the Pacific Northwest. An estimated 1,500 spectators gathered to see Olaf Skjersaa make the first official jump at Skyliner Hill.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the male population in Bend dwindled, heeding the call to join the Armed Forces. Skyliners, along with ski clubs around the Pacific Northwest, went into hiatus.

Returning from World War II, soldiers found solace in family life and it wasn’t until the early 1950s that the Skyliners reorganized. When Bill Healy decided to build a new ski resort in 1958, the members of Skyliners knew the best place around—Bachelor Butte, which we now know as Mount Bachelor.

As a postscript to the tragedy that started it all, the bodies of Cramer and Ferry were finally found two years later, in the summer of 1929. They had perished about 100 yards from each other on the slopes of the Middle Sister. In the raging blizzard, they had become disoriented and climbed the wrong mountain.