Investors flip housing markets, leaving homebuyers reeling

Published 12:00 am Friday, June 21, 2019

- (New York Times News Service)

The house at 1375 Boulevard Lorraine always had what real estate people call “good bones.” A Craftsman-style bungalow, the house was modest — just 1,600 square feet on a single story — but it had a spacious front porch, and it sat on a corner lot atop a sloping lawn that meant passersby looked up at it from the street. It was built in 1935, when this southwest Atlanta neighborhood, known as Adams Park, was a prosperous, middle-class area.

By the time an investor bought it in 2018, however, both the house and the neighborhood had fallen on hard times. Southwest Atlanta had been devastated by the foreclosure crisis, which turned whole blocks into rows of boarded-up houses and overgrown lawns. Boulevard Lorraine, with its canopy of arching trees, never fell quite that far, but it struggled. The property listing for the house called it “a great fixer upper” before warning prospective buyers that it was being “sold as is.” Louis Jackson, an investor operating through a limited liability corporation, paid $85,000 for it.

Trending

There were reasons for Jackson to be confident in his gamble. The BeltLine, a project turning an abandoned rail line into a network of parks and trails, had helped transform much of southeastern Atlanta, drawing a new generation of young, affluent (and largely white) residents to the area and driving up property values.

Now, the BeltLine was being extended to southwest Atlanta, and investors were betting on the same transformation. They bought nearly 26,000 homes in the Atlanta area in 2018, largely in the southwestern quadrant of the city — including at least four on Boulevard Lorraine.

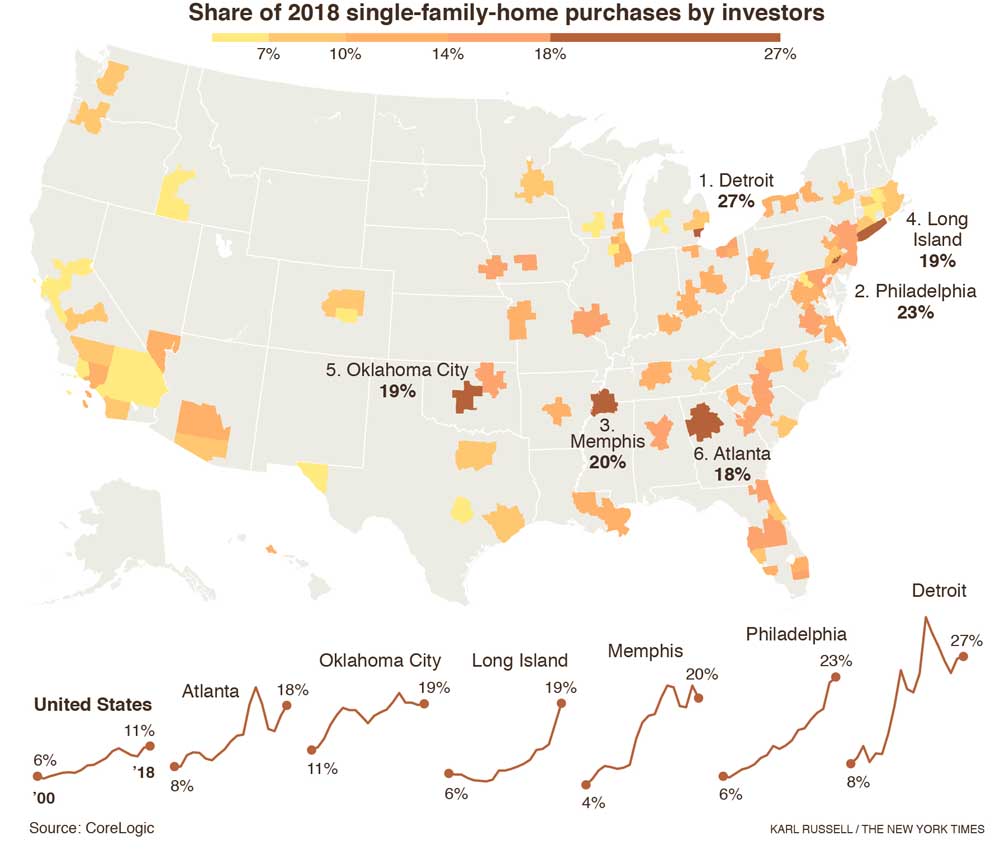

The same story is playing out across the country. A confluence of factors — rising construction costs, restrictive zoning rules and shifting consumer preferences, among others — has already led to a scarcity of affordable housing in many big cities. Investors, fueled by Wall Street capital, are snapping up much of what remains.

“If it weren’t bad enough out there for first-time homebuyers, the additional competition from investors is increasingly pushing starter homes out of the reach of many households,” said Ralph McLaughlin, deputy chief economist at CoreLogic, a provider of real estate data.

Jackson did not have to wait long for his investment to pay off. He sold the home to another investor in May 2018 for $134,000, pocketing $49,000 (minus expenses) after owning it for less than two months.

The couple who bought the house from Jackson, Rebekah Ellis and Jason Makarovich, were already homeowners a few miles away. Ellis, 45, has lived in the neighborhood since 1999; Makarovich, 34, arrived in 2016, part of a wave of young professionals moving into one of the last affordable parts of Atlanta.

Trending

All around them, investors were buying up properties, fixing them up and selling them, often for triple what they paid. When Ellis lost her job in 2017, they figured they might as well try real estate for themselves.

For decades, single-family homes were an investment primarily for people who wanted to live in them. Real estate investors were around, but they were mostly individuals or small partnerships. That changed with the Great Recession and its aftermath, when investors bought at least 2 million homes, and almost certainly far more than that, with prices depressed. Large-scale institutional investors bought tens of thousands of homes for less than they cost to build.

At first, the flood of capital seemed like a one-time opportunity arising from the collapse of the residential real estate market. Once the bargains dried up, the investors were expected to stop buying.

Except they didn’t stop. In 2018, investors bought about 1 in 5 starter homes in the United States (defined as priced in the bottom third of the local market), according to CoreLogic. That was even higher than in the early years after the Great Recession and about double the level of two decades ago. In the most frenzied markets, investors bought close to half of the most affordable homes sold last year, and as much as a quarter of all single-family homes.

The investors take many forms. There are fix-and-flippers who buy homes cheaply and resell them for a profit (sometimes to owner-occupants, sometimes to out-of-towners who rent the homes out on Airbnb). There are those who buy and hold, generally larger institutional investors who rent the properties out. There are traders who acquire properties and try to resell them once they appreciate, sometimes in weeks, sometimes in years.

With all the competition, homebuyers like Fatou Ceesay can feel caught in the crossfire.

An accountant, Ceesay, 38, had a budget of about $300,000 — which was, until recently, more than enough to buy a home in the southwest Atlanta neighborhoods where she has been looking. Even after the area’s rapid price appreciation, plenty of listings were within her range.

But Ceesay has spent more than two years trying to buy a home. Time after time, she has put in offers, only to be told she was beaten out by a cash buyer. Some sellers don’t even give her a chance to bid: They specify they want cash right in the listing. Other times, listings disappear in hours, before she has put in an offer — often to reappear on the market weeks or months later, with $100,000 or more added to the price.

What is happening in Atlanta is partly a familiar story of gentrification pushing up prices and driving out longtime residents. But those trends are being spurred by a fast-growing industry that promotes investment in single-family homes: lenders who provide the capital, brokers who handle transactions, wholesalers who buy homes by the dozens and sell them before they even take possession.

Ellis and Makarovich turned to that ecosystem, borrowing $187,500 to buy and renovate the Boulevard Lorraine house from Angel Oak, a hard-money lender. Days after they closed on the home, Angel Oak announced it had completed a $90 million securitization of similar fix-and-flip loans — meaning it had packaged the loans and sold slices of them to other investors. KKR, the investing giant, recently announced it would invest $250 million — on top of an earlier commitment of the same size — in such loans.

To existing residents, the flood of investors can feel like a threat.

“It’s almost like locusts came down and bought everything up,” said Robby Caban, a neighborhood activist in Atlanta.