The Newberry National Volcanic Monument offers adventure, lessons and relaxation

Published 12:00 am Sunday, June 23, 2019

- The Newberry National Volcanic Monument offers adventure, lessons and relaxation

The chill at the end of Lava River Cave beckons on Central Oregon’s 90-plus degree days, and the rock-laden adventure through the dark cavern gives you that well-deserved reward.

Lava River Cave is 12 miles south of Bend at the Newberry National Volcanic Monument. It’s one of the more easily accessed caves in the area and a popular site for visitors.

Trending

The national monument, established in 1990, features multiple sites people can traverse through the carnage of the sleeping giant. Visitors can easily spend an entire day exploring the spots where the volcanoes flows and fissures found their way through the landscape, leaving massive pieces of the forest black with volcanic rock.

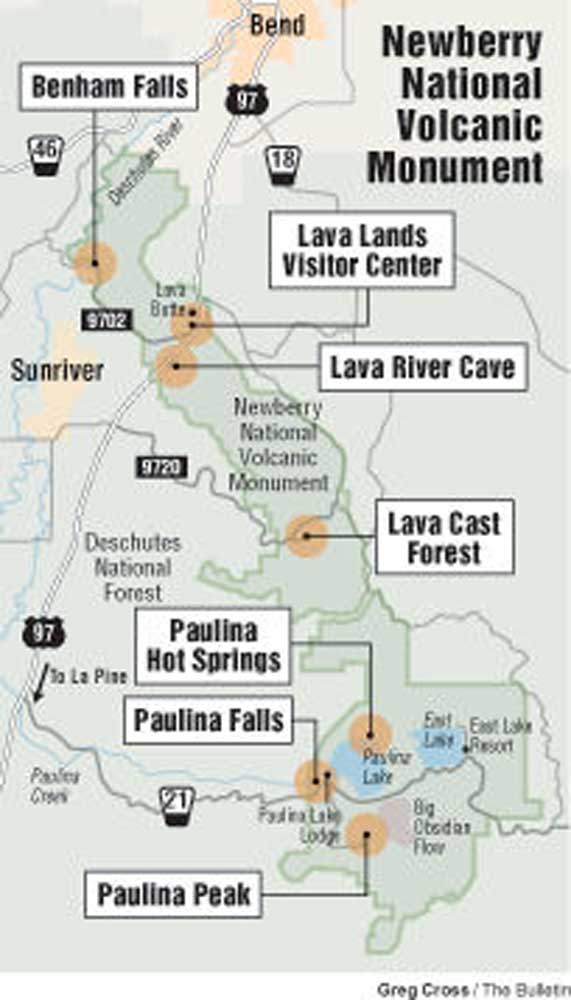

Managed by the U.S. Forest Service, the monument brought together Lava River Cave with Lava Butte to the west and Lava Cast Forest and Newberry Caldera to the south under one umbrella.

The monument is a testament to Newberry’s forces that altered and shifted the landscape to what it is today. Visitors can learn, study and explore it before it wakes again.

Lava River Cave is the longest known continuous lava tube in the state.

As people walk through the cavern, the cool sandy floor quiets each footstep.

Voices and sounds echoing off the smooth rock walls diminish as the cathedral-like chamber narrows and transforms into something the size of a crawl space. Duck down and breathe in the damp, musty cold air.

Trending

You’ll know it’s time to turn around when you see a small sandwich board plastic sign that exclaims, “End of the cave!”

Before you turn around, shut off the flashlight and try to see through the absolute blackness surrounding you until you can’t stand it any longer.

Take a selfie with the sign and start walking.

Newberry Caldera

The view of Newberry Volcano, the mountain that caused the rugged sites now encompassed by the monument, is an unassuming, large ridge to the south of Bend.

Few may realize upon first glance that its a volcano at all, let alone one of the highest-threat volcanoes in the United States.

Not conical in shape like its Cascades neighbors to the west, Newberry is a shield-shaped composite volcano that emerged from the Cascades volcanic chain around 500,000 years ago.

The area it consumes is vast, taking up almost 1,200 square miles of land — roughly the size of Rhode Island.

Newberry Volcano is a broken mountain, collapsing in on itself three times, the most recent being 75,000 years ago. The process formed a caldera, a bowl-like depression in the mountain, the same process that formed Crater Lake.

Like Crater Lake, Newberry’s new caldera soon filled with water, creating a lake of its own. A few more eruptions within the caldera eventually created an isthmus and split the lake into two, Paulina and East lakes.

The shores of these lakes were home to many native peoples throughout history, the earliest evidence of which, a hearth, is said to have been built around 10,000 years ago.

Today, fishermen, campers and hikers enjoy the lakes’ brilliant blue waters.

Both lakes have their own resorts (Paulina Lake Lodge and East Lake Resort) with their own cabins, boat rentals and dining options. There is a $5 day-use fee to park and launch boats from Paulina Lake Lodge and a $5 fee to launch from East Lake Resort. Additionally, visitors must pay a $5 fee to enter the national monument area.

Both lakes also boast their own primitive hot springs, drawing from the incredible geothermal pockets in the caldera. East Lake Hot Springs is a short walk from the boat launch of the same name and is small, shallow and strongly smells of sulfur. Paulina hot springs are about 2.5 miles from the nearest parking area, are bigger, very hot and have no odor. Visitors are asked not to dig out the pools.

Paulina Lake is the only lake with an outlet. The aptly named Paulina Creek pours over the caldera rim creating Paulina Falls west of the lake. The creek then careens down hill eventually becoming a little more than a trickle late in the season before meeting with the Little Deschutes near La Pine.

Standing guard over the lakes is the highest point in the monument, Paulina Peak. Rising 7,984 feet in elevation and about 1,600 feet above the lakes.

A Forest Service road winds up to the craggy point of the peak, but is only open for a short time when the snowpack melts. A 2-mile, out-and-back trail also climbs to the summit.

Piled below the peak is Big Obsidian Flow. As the name suggests, the flow here produced the highly silicate, glassy rock obsidian 1,300 years ago, making it the most recent lava flow in Oregon.

A short 1-mile trail loops through the jagged rock, climbing 500 feet. The trail is narrow in places and requires a little scrambling on occasion. Sturdy shoes and sure footing are key to not scrape against the sharp rock.

Outside the caldera there is even more evidence of volcanism.

As magma searched for other ways to erupt from the volcano, it eventually spewed tentaclelike flows miles underground before emerging and forming cinder cones and vents around Newberry Volcano.

The landscape is dotted with more than 400 of these cones, including Bessie, Mokst, Lava Top, McKay, Weasel and Kelly buttes as well as many others with no formal names.

Lava Butte

Driving south from Bend, it is impossible to miss the tallest cinder cone created by Newberry Volcano — the towering, 500-foot Lava Butte.

Sparsely vegetated on its south side and covered in brown and crimson cinders, Lava Butte stands resolute within the sea of black lava rock that poured out of it 7,000 years ago.

Slow moving lava oozed out of the butte’s southern flank and twisted around to the north and west.

The amount of material ejected from the cinder cone is best appreciated from above.

A narrow and steep road leads to the summit of Lava Butte where a trail circumvents the crater that sent ash and tephra (material expelled from an eruption regardless of size) from the top.

During the summer, a shuttle runs visitors up and down the butte every 20 minutes for a cost of $2 per person. When the shuttle is not in operation, personal vehicles can make the trek, but drivers must get a timed permit from the welcome station outside the Lava Lands Visitor Center.

Not only are visitors greeted with a near perfect view of Newberry Volcano to the southeast and the Cascades to the west, they can see just how far the lava from here traveled, eventually meeting up with the Deschutes River.

The eruption here changed the course of the Deschutes, damming it and creating Lake Benham behind it.

The water eventually worked its way through the rock and cut a new channel, draining the lake and creating Benham Falls.

The Lava Lands Visitor Center sits at the base of the butte and its lava flow. The small center hosts a thorough display on the geologic and anthropological history of Newberry National Volcanic Monument as well as a patio area where rangers and volunteers give regular presentations on the park.

The 1-mile paved and partially wheelchair accessible Trail of Molten Land leads from the visitor center out through the lava field where interpretive signs guide visitors and inform on various volcanic features.

Lava River Cave

Formed around 80,000 years ago, Lava River Cave has been used by humans since they first found it. For settlers, that was in 1889 when Leander Dillman stumbled across it while hunting. He then utilized the cave’s average temperature of 42 degrees for keeping his game cold.

The lava tube was called Dillman’s Cave up until 1921 when Dillman was convicted of a crime and the name switched to its current iteration.

The tube runs about 5,200 feet before sand blocks the passage and lies around 200 feet below ground.

Upon arriving at the cave, all visitors are required to attend a short orientation on white-nose syndrome, a disease that has killed millions of bats across the East Coast and has recently made its way to Washington.

In an attempt to quarantine the cave, the Forest Service requires that no clothing or gear worn or used in any other cave is permitted within Lava River Cave.

They also require everyone to check in at the small booth at the top of the cave entrance. If needed, flashlight rentals are available. Visitors can also bring their own flashlights and headlamps.

The cave is split into two sections, one is too rocky and dangerous for the public and is blocked by a metal gate, the other opens wide with fallen rocks lining the entrance. A set of stairs welcomes spelunkers downward 55 steps and over metal boardwalks until arriving at the cave floor.

The ceiling of the cave is massive, reaching 58 feet high and 50 feet wide.

Voices of excitement reverberate off the smooth walls made of pahoehoe basalt as the cave continues on.

A little less than halfway through, an old melamine sign states that U.S. Highway 97 lies 80 feet above.

The cave constricts and opens up twice before the end, showing off the small stalactites that cling to the ceiling in the low parts, opening up into a double tube until the ceiling begins to get lower and lower until the sign telling travelers to turn back appears.

The section beyond the sign was dug out by two men in the 1930s and is so narrow it requires crawling, which is why the Forest Service closed it off to visitors.

It is not known how much further the tube extends beyond the plug.

Lava Cast Forest

South of the cave lies another lava field in the middle of the woods down a 9-mile dirt and gravel road.

Lava Cast Forest is a smaller field than the one at Lava Butte, but it is no less extraordinary. Here the lava is filled with tree casts from the forest that grew here.

These casts were created when the slow-moving lava began to cool around the trunks of trees before they burned to ash.

Both vertically and horizontally oriented casts are seen from the 1-mile-long, paved and partially accessible loop.

Despite the apocalyptic-looking field, life found a way. Countless numbers of golden mantle ground squirrels scatter as nearby eagles chirp; pikas are heard in the distance and nibble on the flora that grows among the rocks.

Lava Cast Forest is one of the quieter areas of the monument due to its location and smaller scale. The area also has an off-the-beaten-path trail to a kipuka, an island of trees surrounded by lava, known as Hoffman Island.

The trail to the island is 1 mile out and back and traverses through the sea of lava to the wooded area beyond. The temperature can climb on the lava, making this island of pines a cooling retreat for sun-baked skin.

The massive lava fields throughout the monument hold an otherworldly quality about them; it’s no wonder NASA came calling.

At the start of the Apollo program, NASA began sending their astronauts to geologically important areas in the U.S., Mexico and Iceland to explore, learn about and do field tests on the terrain similar to what they may encounter when landing on the moon.

In October of 1964, several astronauts came to the Newberry Volcanic area to do just that, including Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong.

Another group would visit the Central Oregon area in July of 1966.

One astronaut from this group was sent a small piece of lava rock from Devils Lake off the Cascade Lakes Highway and left it on the moon in 1971.

Take a moment

Newberry National Volcanic Monument is open seasonally.

Lava River Cave shutters in October to protect hibernating bats and the roads to the caldera; Lava Cast Forest and Lava Lands all close with the arrival of snow.

Even with the shortened time to visit, and the amount of people that do so, it is still possible to steal away those quiet moments. To turn off the flashlight and feel the total darkness settle around you, to eat a Popsicle and watch the shadows grow longer on the shores of a lake, to wander through the forest and then through an ancient lava field. And be sure to breathe in the sweet smell of pine and watch the sun dance off the side of Paulina Peak as it looms over the monument.

—Makenzie Whittle is a Bend native. She and her family have taken day trips since she was an infant, exploring the far-reaching corners of Oregon. She continues the tradition today, and can be reached at 541-383-0304 or mwhittle@bendbulletin.com