The long and surprising history of roller derby

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, July 30, 2019

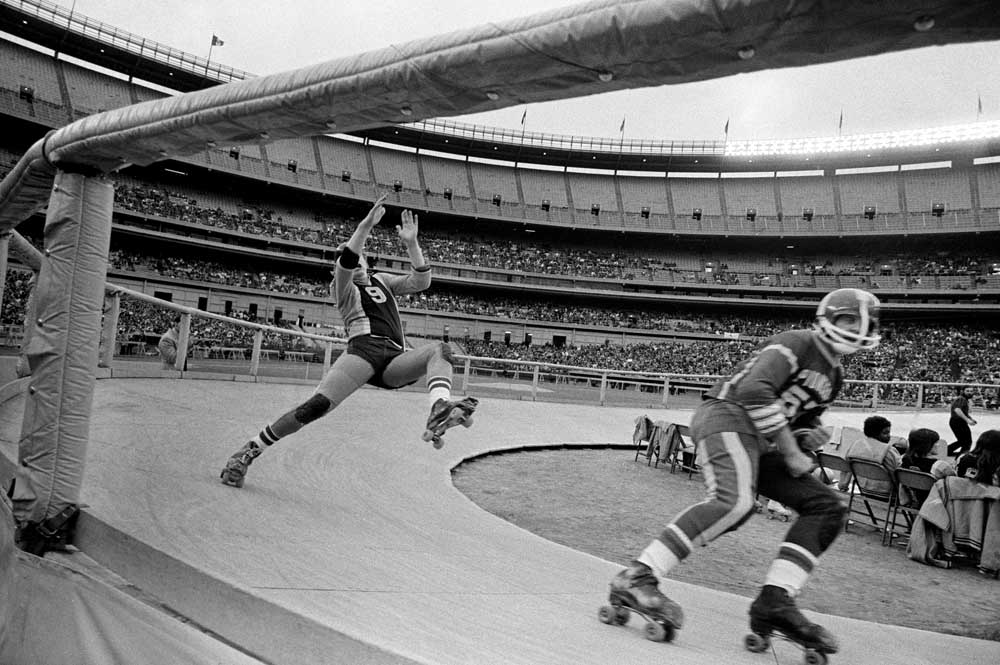

- FILE — The Midwest Pioneers' Bob Hein sends Jerry Cattell of the Cincinnati Jolters flying as he passes him in the first match of the world championships at Shea Stadium in New York, May 26, 1973. From the beginning, roller derby offered an equal playing field for men and women: same rules, same track, same helter-skelter rush. (Michael Evans/The New York Times)

It sounds like a human freight train: wheels clattering around the turns, bodies thumping against each other, toe stops shrieking against the track. A rainbow of hair and wheels goes by in a blur, shouts and grunts punctuating the din. It is part endurance race, part wrestling match, combining strategy, athleticism and camp. And it is all done on roller skates.

At first glance, roller derby seems like a feminist punk fever dream. It is unapologetic and aggressive, a full-contact whirlwind populated by characters with names like Carnage Electra, Miss U.S. Slay and Bleeda Kahlo. But the blood, sweat and mascara that seem so essential to the modern sport have roots stretching back nearly a century.

Trending

“For women to have been playing a contact sport back in the 1930s was unheard-of,” Margot Atwell, the author of “Derby Life: A Crash Course in the Incredible Sport of Roller Derby,” said in a phone interview. “Feminism is in the DNA of the sport. And having a space that centers female and gender-expansive aggression is really important.”

Roller derby was born Aug. 13, 1935, at the Chicago Coliseum. The story goes that Leo Seltzer, an event promoter who had cut his teeth on walkathons, was looking for something a little more exciting to draw Depression-era crowds. After reading in a magazine that more than 90% of Americans had roller-skated at some point in their lives, he decided to put his show on wheels.

Twenty-thousand people came out for the first Transcontinental Derby to watch two-person teams, each consisting of a man and a woman, skate 57,000 laps around a flat track, Keith Coppage writes in “Roller Derby to RollerJam: The Authorized Story of an Unauthorized Sport.” Small lights on a large map tracked the skaters’ progress as they took turns whizzing around the ring, their mileage blinking along the route from New York to San Diego. The first team to complete the roughly 2,700 miles from coast to coast was declared the winner. On average, a single marathon took more than three weeks.

Worried that the endless laps were getting, well, repetitive, in 1937 Seltzer turned to sports writer Damon Runyon. Together, they created what would become the enduring structure of roller derby and introduced the full-contact thrills that define the sport today.

In each bout, as a roller derby match is called, 10 skaters at a time take to the track. There are five players from each team: one jammer, whose job is to lap the other team and score points, and four blockers, who try to stop the other team’s jammer and clear a path for their own. At the start of each round, known as a jam, the two jammers race to get out of the pack first. Whoever prevails becomes the lead jammer. The jam then goes for two minutes, with teams earning a point every time their jammer laps a member of the opposing team. The lead jammer can also end a jam early by tapping her hands repeatedly on her hips.

“It’s a very physical and mental game,” says Danielle Sporkin, aka Spork Chop, the league president of New York’s Gotham Girls Roller Derby. “It’s one of the only sports where you’re playing offense and defense at the same time.”

Trending

By 1949, roller derby had become a national sensation, with skaters like Billy Bogash, Gerry Murray and Midge “Toughie” Brasuhn becoming well-known names. ABC broadcast the bouts up to three times a week. Mickey Rooney took the sport to the silver screen in the 1950 film “The Fireball” (which also featured a 24-year-old rising star named Marilyn Monroe). That same year, the short film “Roller Derby Girl” was nominated for an Academy Award.

But just as quickly as it had flamed into the public consciousness, roller derby faded. By 1953, with public interest waning, Seltzer moved his operation to California. He held a final New York training camp to recruit new skaters.

Judi McGuire, already a U.S. flat track speedskating champion, was a senior in high school when some friends invited her to check out the derby training program. On her second day, she said, she was drafted.

“One of the girls on the New York team had to leave because she was pregnant, so I got her spot,” recalled McGuire, who is 79 and lives in Escalon, California. “I was skating Thursday through Sunday and then going to school the rest of the week.” She graduated in June and left the next day for the West Coast.

In 1959, Leo Seltzer handed the reins to his son, Jerry. The younger Seltzer decided to take a new tack: Maintain the athleticism of roller derby while upping the drama. He also started videotaping the games and licensing them to local TV stations.

Roller derby blazed back into the zeitgeist. In 1965, 13,421 fans thronged to watch the championships when the skaters returned to Madison Square Garden after a 13-year absence. By 1971, the crowd had swelled to more than 19,000. And just as in the sport’s earliest days, men and women skated by the same rules, for the same amount of time, on the same track.

The drama of roller derby during Jerry Seltzer’s tenure was cinematic, with festering feuds playing out over weeks and brawls breaking out mid-jam. McGuire insisted that the bouts were never fixed. (Jerry Seltzer waffled on the issue.) But even if the theatrics were, for the most part, organic, the casting of certain teams and players as villains or heroes had striking parallels to the melodrama of professional wrestling.

And whether it was faked may not be the point: As Frank Deford wrote in The New York Times Magazine in 1998, not to go “just because you knew the Bombers would prevail on the last jam was not to go watch Dame Margot Fonteyn dance Aurora because you knew how ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ would turn out.”

In May 1973, 27,135 fans packed into Shea Stadium to watch the triple-header world championships, in which the Chiefs, led by Mike Gammon, defeated the Pioneers 34-31. He and McGuire, married at the time, were featured the following March in People magazine. They had a deal with Doubleday to write a memoir, “Ram, Slam, Jam and a Little Bit of Ham.” But by the end the year, the roller coaster of derby came, again, to a crashing halt.

“We never got a reason,” McGuire said. “It was a cold way of closing our career. And it was confusing, because the crowds were still so big.”

Jerry Seltzer sold the rights to the International Roller Derby League to Roller Games, a rival league based in Los Angeles. They lasted a few years longer than he had, even staging a bout at Madison Square Garden between the Tokyo Bombers, Japan’s first professional roller derby team, and the Chiefs that drew 14,251 fans in February 1974. But by 1975, Roller Games too had gone belly up.

And so it seemed roller derby had gone the way of walkathons and dance marathons. There were a few attempts to bring it back in the 1980s and ’90s — in increasingly exaggerated, WWE-esque forms — none of which went anywhere. But then, in 2001, a group of women in Austin, Texas, resurfaced the sport, combining the traditional structure with a decidedly feminist bent.

“There are very few spaces in the world where women, transgender and gender-nonconforming folks get to use their bodies freely and unapologetically,” Molly Stenzel, the president of the Women’s Flat Track Derby Association, or WFTDA, the sport’s main governing body, said in an email. (Stenzel is better known to her fellow skaters as Master Blaster.)

In addition to full-contact aggression and women’s empowerment, roller derby today is known for the skaters’ creative, often pun-laden names — a tradition started by the founders, who were inspired by Austin’s drag scene.

“People take these names, and they’re kind of goofy, but it also frees you up,” said Margot Atwell, aka Em Dash. “It’s not an alter-ego: It’s a way to be more yourself than you can always be in your normal life.”

Last year’s WFTDA world championships, in New Orleans, drew 2,500 spectators. Someday, Atwell said, she hopes they will return to Madison Square Garden.