OSU researcher makes breakthrough toward finding osteoarthritis therapies

Published 10:00 am Monday, December 2, 2019

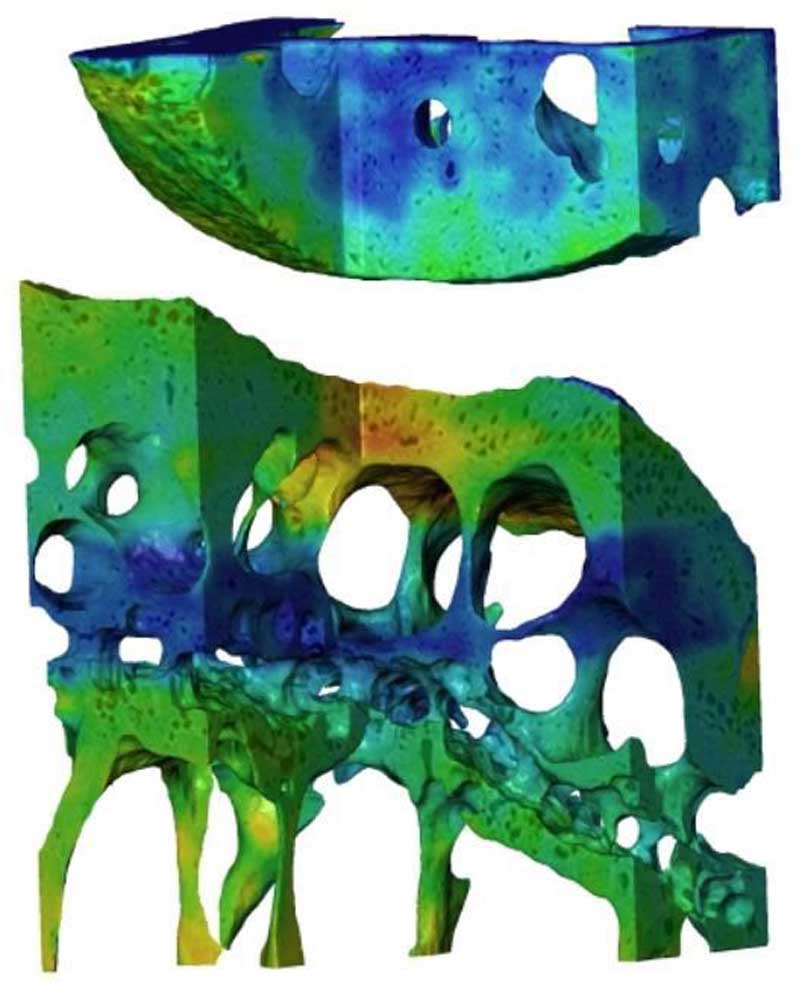

- Nanoscale image of mouse joint. [Oregon State University]

Researchers at Oregon State University are one step closer to curbing osteoarthritis after making a breakthrough by providing the first ever complete look at what’s happening to joints with the condition at the cellular level.

Brian Bay, a researcher in OSU’s College of Engineering, published a study this week in the Nature of Biomedical Engineering alongside scientists from the Royal Veterinary College in London, according to an announcement on the college’s website.

Trending

Together they developed a “sophisticated scanning technique” that allows them to see the “loaded” or strained joints of arthritic mice versus healthy mice and understand factors that affect them.

Osteoarthritis is a condition where the joints deteriorate. It affects more than 50 million American adults, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and that number is expected to climb to 78 million by 2040.

Up until now, the imaging for arthritic joints and the ability to quantify any change was restricted because of factors such as damage to samples being scanned with methods that relied on high levels of radiation.

“Nanoscale resolution of intact, loaded joints had been considered unattainable,” said Bay, who is an associate professor of mechanical engineering.

But now, with their new imaging method, the researchers can see complete, deep tissue layers. By using a low-dose pink beam radiation X-ray, and “mechanical loading with nanometric precision” the scientists can look at joints from the tissue layers down to the cellular level, without compromising samples and keeping a high resolution, according to the OSU website.

The group has been studying the changes in mice, but they hope the new ability to see osteoarthritis at the cellular level will lead to potential therapies for osteoarthritis to help people avoid joint replacement.

Trending

“Using intact bones and joints means all of the functional aspects of the complex tissue layering are preserved,” Bay said. “And the small size of the mouse bones leads to imaging that is on the scale of the cells that develop, maintain and repair the tissues.

“It’s a breakthrough in linking the clinical problem of joint failure with the most basic biological mechanisms involved in maintaining joint health,” Bay said.