Concept artist John Bell lands in Bend

Published 2:00 am Sunday, March 15, 2020

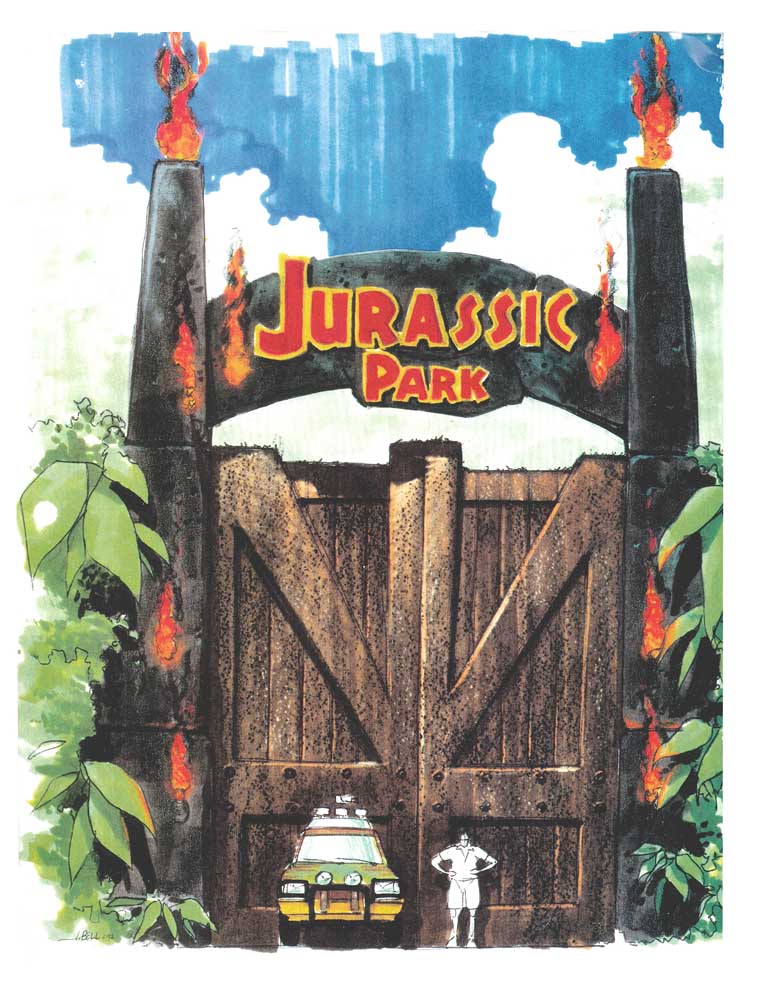

- Bend artist John Bell’s concept art for the main gate in “Jurassic Park.”

Between the mid-1980s and 2018, Bend artist John Bell created concept art and storyboards for some of the era’s most memorable films.

Concept artists serve as a visual bridge between words and ideas in a script, conceiving a film’s visual look long before audiences see them realized on screens. Bell conceptualized scenes and props for films including “Back to the Future 2,” “The Rocketeer,” “Jurassic Park,” “Contact,” “Antz,” “Rango” and many others.

Bell also drew storyboards, which show the sequence of action in a scene. According to longtime film colleague and fellow artist David Nakabayashi, Bell “was always an illustrator that people respected very highly. (Filmmaker Steven) Spielberg really loved his storyboards. He was always, ‘Where’s John Bell? Get John Bell in here.’”

Bell’s work was also popular among other film industry artists, who often imitated his style, Nakabayashi said. “Myself included.”

In January, Bell began work as a video game concept artist at Sony Interactive Entertainment’s Bend Studio, the latest move in a fascinating art career that he started as a teen in Montclair, New Jersey.

The youngest of three boys, Bell and his brothers shared the hobbies of drawing and building models. Their father, Bill Bell, worked in marketing at CBS Records in New York City, but John Bell never got to meet any of the label’s artists before his father quit at age 50 in order to pursue painting full time.

“He never wanted to go back into the city on the weekends,” Bell said. However, his father took him and his brothers one place that proved fruitful for Bell.

“Dad used to take us down to our local drag strip. We kind of fell in love with the color and the noise and the excitement of the cars,” he said.

Bell began to connect with some of the drivers, designing paint schemes for their cars, with pay. “To a 16-year-old, that was pretty exciting,” he said.

Bell credits much of his future career success to good timing. For instance, the time his dad was out West on business and mentioned to someone in a bar that his youngest son liked to draw cars. That person told Bell’s father about the Transportation Design Program at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California, whose alumni designed Corvettes, Camaros, Mustangs and other classic cars.

Bell applied and got into the school, which was very competitive, but also supportive.

“The daily critiques could unravel you if you let them, or you could see them as a learning experience,” Bell said.

After graduation, he worked for General Motors in Detroit, Michigan.

“Detroit in the … early ’80s was kind of a rough spot. They weren’t doing very well because of all the Japanese imports,” he said.

In 1982, about two years after he’d started at GM, “another weird timing thing” occurred, Bell said. An old classmate from the ArtCenter called from San Francisco, where he worked for Atari, then the big player in the new home video game market. The man invited Bell to interview with Atari, where he landed a job helping to design video games for the company that brought the world Space Invaders.

“So now I’m in the Bay Area in the early ’80s,” Bell said. However, Atari started to take a serious dive in ’84, ’85” due to competition from other game systems and other factors.

The future at Atari was not looking too bright, but “the Bay Area was pretty fun,” he said. “I looked around, and I saw that Industrial Light & Magic, Lucasfilm, was in the Bay Area.”

That’s “Lucas” as in George Lucas, the famed creator of “Star Wars” and numerous other films. In the mid-70s, Lucas founded Industrial Light & Magic, or ILM. Along with the “Star Wars” films, the company’s effects can be seen in franchises including “Indiana Jones,” “Jurassic Park,” “Harry Potter” and “The Avengers,” and films such as “E.T.,” “Saving Private Ryan” and “World War Z.”

Bell found ILM’s address and sent a cover letter and work samples. For months, he heard nothing.

“Then one morning, I was getting ready to go into work at Atari, and my wife at the time said, ‘You’ve got a phone call from somebody at ILM,’” Bell said. “I thought she was kidding me. … She goes, ‘No, there’s somebody really on the phone. They really want to talk to you.’”

He went in for an interview and landed a job with ILM. His first project was as assistant visual effects art director on 1986’s “Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home” — still another film franchise for which ILM provided effects. (“The one with the whales.”) He didn’t meet Lucas until he worked on 1988’s “Willow.”

“George would come in, and he wouldn’t say anything,” Bell said. “He’d have all your artwork on the wall. There’s three of us in the art department. He’d come in, grab a red marker and he’d walk over to the wall and just mark the ones that he liked. And then he put the marker down and he goes, ‘Well, I’ll be back next week.’ And that was his input.”

Bell wasn’t intimidated meeting the already very famous Lucas, “because he was so quiet. He just kind of walked in there. He didn’t make a lot of eye contact.”

“Willow” was directed by Ron Howard, better known at that time for his acting work in roles such as Opie on “The Andy Griffith Show” and Richie on “Happy Days.”

“When I saw him sitting in the chair in the room, and I got introduced to him, all I could think was ‘Don’t say Opie,’” Bell said.

More films followed, including Francis Ford Coppola’s “Tucker” (1988), a historical drama starring Jeff Bridges as auto designer Preston Tucker. Given the prominent role of cars in the film, it was very much in car-lover Bell’s wheelhouse. Along with drawing storyboards, he was asked to help Bridges prep for a courtroom scene.

“They were going to have a shot of him doodling up the shot of his next car drawing. I went over to him, and I’m saying, ‘OK, I don’t know if you’ve ever drawn before. These are just some simple things, you know, perspective.’ … Just rudimentary stuff. He was kind of looking at me like, ‘OK, kid, just finish this up so I can go back to the set.’”

Next came 1989’s “Back to the Future Part 2,” director Robert Zemekis’ sequel to 1985’s “Back to the Future.” After traveling to 1955 in the first film, Michael J. Fox’s Marty McFly travels forward to 2015 in the first of two sequels.

In one famous sequence from the 1985 film, McFly converted a scooter into a makeshift skateboard. Naturally, he needed an upgrade in 2015. As concept artist, Bell envisioned and drew the hoverboard seen in the film.

“It’s amazing how that one prop has resonated so solidly with so many people,” Bell said.

In 1990, “Back to the Future Part 2” was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, and won a British Academy of Film and Television Arts Award.

In 1989, Bell hired fellow ArtCenter graduate David Nakabayashi at ILM. The two have remained friends for three decades.

Bell brings a unique perspective to his work, Nakabayashi said.

“Because he was a car designer before he was working in films, there’s a practicality to his work that people right away connect with. Everything looks like it could work. There are people in our industry that do great artwork, and they’re illustrators. And then there’s designers — people who really come forward with strong ideas, and he happens to be both … because he draws exceptionally well.”

Once he’d completed work on 1991’s “The Rocketeer,” Bell began considering a shift in his art career. He next worked as co-art director on 1993’s “Jurassic Park,” after which he landed a job at Nike and moved to Portland. He loved the town, but shoe design work for the massive company was not a great fit.

“It was a lot like the car industry, where, you know, the human foot’s not changing, so you can only change up the designs so much. At the time, I wanted more variety, and they had promised me more variety when the job offer came up,” Bell said. “When I got up there, it was just, ‘Nah, you’re gonna do footwear.’ So I kind of ran out of steam.”

A couple of years later, Bell returned to the Bay Area and worked on late-90s films including “The Lost World: Jurassic Park,” “Men in Black,” “Starship Troopers,” “Contact” and the computer animated “Antz.”

Around 2000, he returned to video games, freelancing for Electronic Arts, mostly working on intellectual property ideas.

“The couple of games that did come out were a “Simpsons” game and a “James Bond” game and a “Godfather” game,” he said. “Can you believe they made a game out of ‘The Godfather’? We were all scratching our heads. That movie is about food and discussion.”

More than 20 years after being hired at ILM by Bell, Nakabayashi returned the favor, bringing Bell back for the animated 2011 film “Rango,” starring Johnny Depp. Bell remained at ILM through the fourth “Pirates of the Caribbean” movie, before returning to Electronic Arts. Bell also freelanced on storyboards for the 2015 film “The Revenant” and Spielberg’s 2018 film “Ready Player One,” but most of the past decade has been dedicated to video games.

With their kids in their 20s, Bell and his wife, Wendy, began to get serious about moving to Bend, a city they had visited several times.

“It was a place we had been planning on moving to,” he said. “And then another weird thing happened. I was on LinkedIn and I saw this woman’s name that I was familiar with. I saw her title was a recruiter at Bend Studio. I thought, ‘I remember her from DreamWorks, and I’m just going to write her a letter and say, “Hey … if you know of any concept art positions, let me know.”’”

He doesn’t really miss creating concept art, at least not in today’s film industry.

“The way that (film) concept art is now created, you have to render it so much to look like a photograph before it gets shown to a director, or before it gets shown to an effects supervisor. That shouldn’t be the case,” he said. “That’s why it’s called concept art. It’s not a rendering of the frame of the film. … It’s ‘I took your words from the script. I interpreted it into a picture,’ which is fairly loose. I mean, it’s clear enough where you know what’s going on, but it’s not crossing every t and dotting every i. That part I don’t miss, because it’s just gotten so tedious.”

Said Nakabayashi, “He’s certainly more of an idea person. … Directors want to see things that are more photo-realistic. His work is not that. It’s much more conceptual. … The guy draws with a ballpoint pen. That’s his tool of choice. Just with that alone, you can get a lot of life off the page.”

Bell said that his father’s shift to painting full time at 50 has stuck with him.

“I wanted to do the same, but it just didn’t work in my favor,” he said. “Eventually I would like to make a living off of my own work.”