Teachers find complex solutions for students with hearing, sight impairments

Published 5:00 am Thursday, November 19, 2020

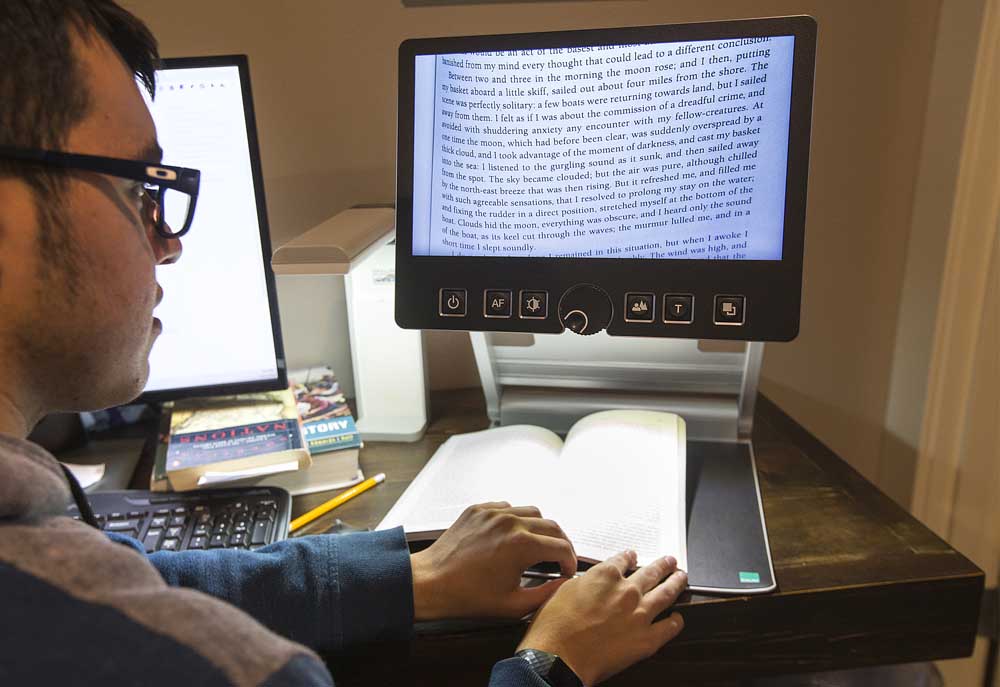

- Michael Sawyer uses a portable magnifier to read the pages of a book while doing schoolwork.

Michael Sawyer’s desk has so many computer monitors that it looks like a scene from the TV police drama “CSI.”

The Ridgeview High School junior from Redmond is vision-impaired, so his school-issued laptop is hooked up to a larger monitor that enlarges the text of online assignments. Michael also has an electronic magnifier, which he puts textbooks underneath to make them readable.

Michael acknowledged that using all these gadgets just to keep up is challenging. But the 16-year-old student said he completes assignments successfully despite this extra hurdle.

“It’s a little bit more difficult than normal school, but it works for the time being,” Michael said.

Michael is one of many students in Central Oregon with either vision or hearing impairments who require unique, complicated workarounds to learn remotely while schools are closed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A team of teachers from the High Desert Education Service District helps these students in Deschutes, Jefferson, Crook and Harney counties. And although it can be difficult, the teachers say they relish assisting students with physical impairments.

“We enjoy, so much, helping students approach these hurdles and figure out how to still have access,” said Nancy Abbott, who teaches blind and vision-impaired students. “We want to help them jump over the hurdles with excitement.”

The move to distance learning has created new challenges for blind and vision-impaired students, Abbott said.

In particular, the increased dependence on online classroom management systems like Canvas, on which voice control features don’t always work, is tricky, she said.

For one blind La Pine High School junior, three devices are required just so the 16-year-old girl can learn from a video. There’s one device with video chat connecting Abbott and the student, one device in the student’s room for completing the assignment, and a third device in Abbott’s room where the video plays, so Abbott can describe the images on screen.

“It’s very hard for a blind student to have the same access to things,” Abbott said.

Furthermore, written online worksheets and reading materials must be translated into Braille, delivered to blind students, then the student and the teacher must read the material together over Zoom, Abbott said. For students who are still learning how to read and write in Braille, this is a major downgrade from teaching in-person, she said.

“Instead of being able to do it in-person, with me next to them helping their hands guide, I’m doing it over a Zoom call,” Abbott said. “I’m like, ‘Can you move your camera so I can see where you are?’”

Some blind or vision-impaired students Abbott normally works with have given up and severed contact, due to how difficult distance learning is for them, she said.

“We keep trying (to call), but sometimes their parents won’t answer back, or they’ll say, ‘Nope, we’re homeschooling for now, we’re just done,’” she said.

Extra distance-learning assistance is also needed for deaf and hard-of-hearing students.

Students that rely on a sign-language interpreter must use two devices: one with the same video chat that all students see, and another with the interpreter. Going back and forth between the two screens can be fatiguing for these students, said Tamara Zawacki, who teaches deaf and hard-of-hearing students with the High Desert ESD.

And if that student’s home has a lot of background noise, it can make learning even trickier, added Susan Newman, a fellow teacher of local deaf and hard-of-hearing students.

“Families with more than one school-aged child on computers, accessing different instructors and different programs, there’s a lot of background noise,” Newman said. “That makes it more difficult to focus, of course.”

Some deaf and hard-of-hearing students attend limited in-person instruction, where they’ll work in a small group inside a school building for just an hour or two. But face covering requirements make lip-reading a challenge, Zawacki said.

Still, some deaf and hard-of-hearing students are excelling in distance-learning, Zawacki and Newman said. Extra support from parents can help, and some students prefer more individualized learning, they said.

“Some students thrive in this setting, because they thrive in a one-on-one situation,” Zawacki said. “Maybe there are too many distractions in a classroom setting.”