The truth about fairy tales

Published 3:15 pm Wednesday, August 18, 2021

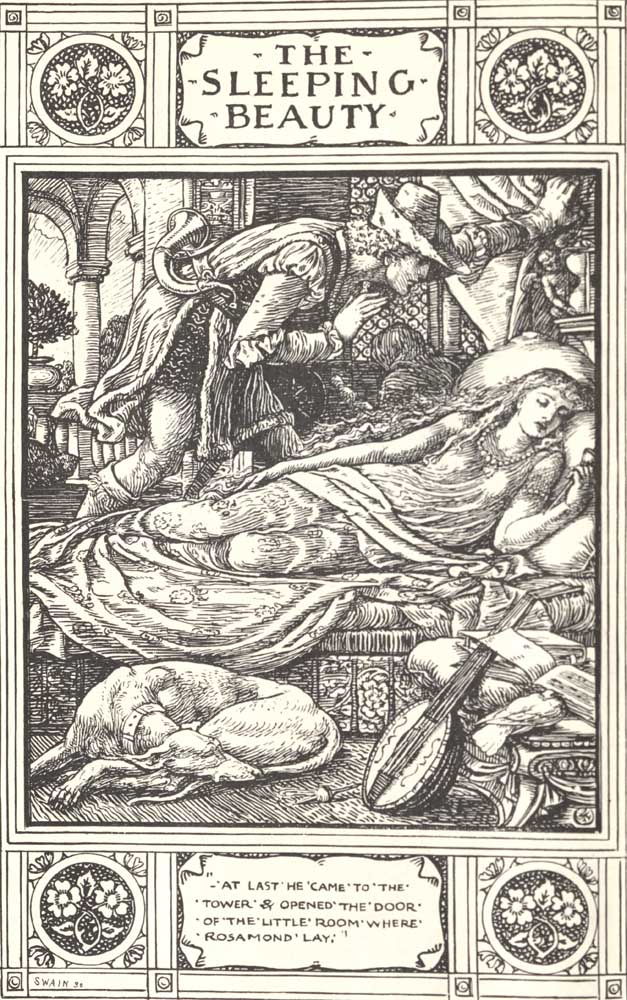

- An illustration by Walter Crane from an 1882 edition of “Household Stories by the Brothers Grimm” depicting their version of “Sleeping Beauty.”

Disney really has done a number on the world of fairy tales. Not only did they give us some unrealistic expectations on what life and love would look like (granted, most of the relationships depicted in the pre-Disney renaissance of the ’90s were a little misogynistic, but I digress), they also skewed the darker origins for a light and bubbly, Technicolor audience and filled it with ditties that still manage to get stuck in your head.

Essentially written as morality and cautionary tales spurred by real-life misfortunes — don’t go into the woods or else a wolf will eat you (“Little Red Riding Hood”), don’t judge a book by its cover (“Beauty and the Beast”), beauty conquers intelligence (“Snow White,” remember when it was written) — these original stories from centuries ago painted much darker pictures than what Hollywood has churned out. Here are just a few of the origin stories behind those cheery toons.

Trending

Cinderella

The threads of this story can be traced back to ancient Greece with the Strabo story of an Egyptian king who marries an enslaved Greek girl sometime in the first century. The movie version more closely resembles the Charles Perrault story of 1697, which is pretty much the happily-ever-after story you expect. However other versions, like “Aschenputtel,” penned by the Brothers Grimm in 1812, is far more gruesome.

In it, the prince goes door to door with the lost slipper to try and find the mystery lady whom he danced with at the ball, and he winds up at Aschenputtel’s home. There, the stepsisters attempt to finagle their way to the crown with one cutting off her toes and the other cutting off her heel in order to fit in the shoe. When the prince asks about another woman in the house, Aschenputtel’s father tells him that there is one that is unseemly dirty, but she comes out anyway, all cleaned up, and when she tries on the shoe the prince recognizes her immediately.

It gets worse. In an addition made in 1819, at the wedding of Aschenputtel and the prince, she gives her family a chance to make amends, but they don’t, so she sics the magical birds (who take the place of a fairy godmother in this story) on them and they pluck out their eyes. Aschenputtel leaves them all behind and lives her happily ever after, despite the bloodbath behind her.

The Little Mermaid

The original story by Hans Christian Andersen is super sad. In it, mermaids have no soul and can live for 300 years and then turn to sea foam.

Trending

One day, the eponymous mermaid sees a handsome prince and saves him from drowning, leaving him on the shore to be discovered by a pretty princess and her ladies in waiting. The Little Mermaid then decides to get him to fall in love with her in order for them both to go to heaven and have their souls intertwined for eternity.

She visits the Sea Witch and trades her voice in for a pair of legs, which the Witch warns her will feel like she’s walking constantly on knives. But she can only gain a soul if the prince falls in love with her and marries her. Otherwise, she’ll dissolve into seafoam.

The prince finds her on the shore after she’s got legs and is struck by her beauty. Despite her not being able to talk, he likes her — especially when she dances, which she does in spite of the sharp pain.

They do fall in love, but the prince’s parents have already arranged his marriage to a neighboring princess. It turns out that that princess is the one who found him on the beach, and since the prince believes that she is his rescuer, he leaves the Little Mermaid.

She’s then given a choice: Kill the prince and become a mermaid again, or die of a broken heart. She chooses the latter.

Sleeping Beauty

This one, we can be glad Disney cleaned up a little, as it is a doozy that involves rape and attempted murder.

The earliest written version seems to come from between 1330 and 1344, by Giambattista Basile. In it, a woman named Talia is thrown into a deep, death-like sleep after being splintered by a piece of flax.

When her father abandons her and their home, she is eventually discovered by a passing king who finds her while he’s out hunting. When he sees her, alive but unconscious, he finds her beauty captivating, so he rapes her and leaves. (The story has better language for the act, “gather the first fruits of love,” but it’s still sexual assault.)

She’s woken up nine months later when she gives birth to twins who suck out the flax splinter. Eventually, the king returns and sees that she’s awake, so he explains who he is and they bond over their new family. He then leaves to go back to his kingdom, vowing to return and take her with him.

Turns out the king is already married, and when the queen finds out about this other family, she forges a letter in the king’s name to Talia urging her to send the twins to the castle. She does, and the queen instructs the cook to kill the children and cook them.

The cook (the only one with a conscience in this story besides Talia) decides not to cook them and serves lamb instead, with the queen still believing it’s the twins.

So she now sends for Talia, whom she intends to burn at the stake. Eventually, the king finds out and orders the queen and those who helped her to be burned. He thanks the cook and marries Talia. Big “yikes” all around.