Adult connections, shelter are key Central Oregon houseless youth graduation rates

Published 5:00 am Sunday, October 17, 2021

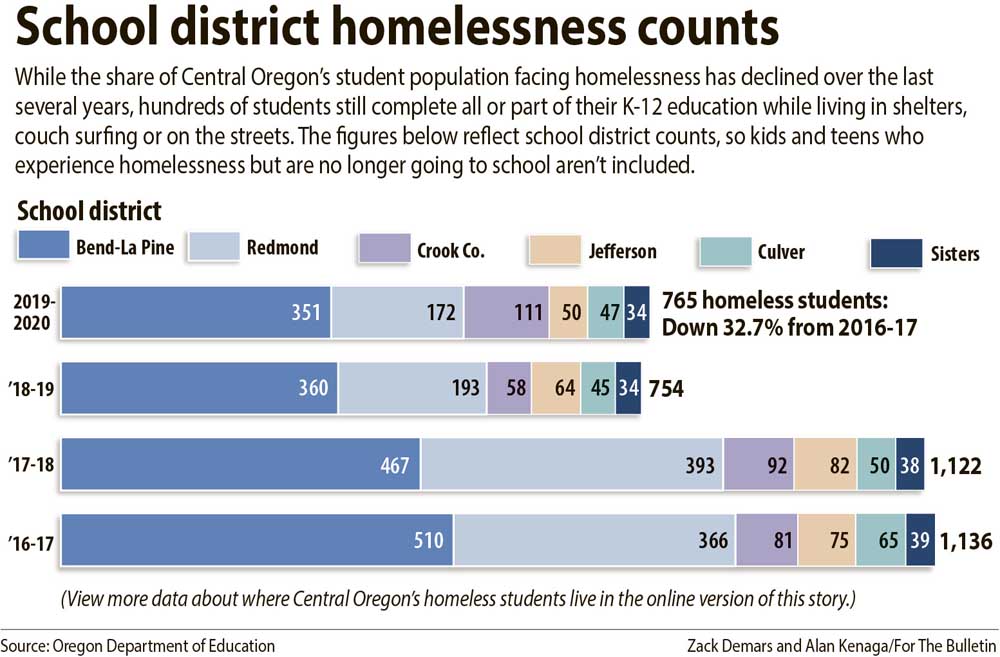

- print only homeless students chart

Uriah Barzola danced along the sidewalk the last time he walked home from Bend High School last spring.

He’d been offered a ride, but he’d walked to school every other day. It felt right to make the walk one last time, listening to The Beatles and “rocking out to some Paul,” just like he had on the first day of school.

Soon, a group of people sitting around a fire started cheering as he passed their backyard. Barzola, 19, wondered why — until he remembered he still had his diploma in hand and cap and gown on.

“It’s because I graduated,” he remembered.

Amid the joyful walk last spring, Barzola realized he’d left campus for the last time — but had he forgotten anything in the building? The popcorn he’d stored there? Any of the clothes he’d washed in the school’s laundry machine, which he used for months while being homeless?

The Bulletin and the City Club of Central Oregon will co-host a forum on the graduation rates of homeless students on Oct. 21. Hear from some of the community members in this story, and ask them your own questions. More information about the forum is available online at cityclubco.org.

A Solutions Workshop hosted by The Bulletin will follow the forum on Nov. 4. Invited change makers and experts will come together to form responses for Central Oregon.

Oregon students who spend any part of their education homeless are far less likely to graduate high school than any group of their peers. Despite gains in recent years, the barriers these students continue to face keeps a diploma out of reach for many and perpetuates a cycle of lifelong homelessness.

The numbers are stark. In the 2019-20 school year, the last for which data is available, 60% of Oregon’s homeless students graduated, compared to 83% of the state’s entire senior class. Rates in Central Oregon’s larger districts ranged between 47% and 73%, all below the rest of their districts’ senior classes.

Those rates have increased in recent years, and education leaders are focusing on the population. There’s no one thing that gets any student to graduation, but many grads who experienced homelessness point to the relationships they’ve built with school staff, academic support programs, local shelters and resource navigators.

Those graduation rates are about more than individual success, according to Barbara Duffield. She leads SchoolHouse Connection, a nationwide nonprofit which advocates for “overcoming homelessness through education.”

While most Bend residents might imagine the “average” homeless person as a 52-year-old man living in a tent on Emerson Avenue, Duffield says that failure to see the child that man used to be just perpetuates a cycle of homelessness.

“It actually contributes to having more 52-year-olds on the street. Because as long as the problem is invisible and not understood, it’s not addressed, it’s deprioritized,” Duffield said. “There’s not enough shelter space for them. They can’t sign a lease, so they’re going to be in these hidden situations where they’re moving from place to place, and that is actually, in some cases, more vulnerable than being outside, because they’re at risk of predation and trafficking. They’re eating less in order to be staying where they’re staying, they’re always worried about where they’re going to be.”

A 2019 study from the University of Chicago showed the two-way relationship between housing and education: Young adults without a high school diploma or GED were 4.5 times more likely to be homeless, and those who were homeless were one-third as likely to go to college.

It’s not just Oregon. About 68% of homeless students nationwide graduated in 2019, the lowest rate of any subgroup, according to federal statistics.

Barzola still remembers the day late in his sophomore year when he got the text from his mom saying he needed to find somewhere else to live.

“Panic. Total and utter panic. It’s, ‘where am I going to live?’” he said. “It was a total week and a half of just panic — where am I going to live tomorrow?”

For that week and a half, Barzola worked with teachers and school staff to try and find him a place to live.

Steve Wetherald, a Bend High special education teacher who’d watched Barzola blossom from a student who struggled with some basic school skills into someone who wanted to learn, was one of those teachers. He helped Barzola move into The LOFT, Central Oregon’s only homeless shelter for youth, quelling some of the teen’s panic.

During the weeks of anxiety leading up to the move out of his mom’s house, school fell onto Barzola’s backburner.

“The struggles that he was facing, it’s really hard to think about English class. It’s really hard to think about applying to colleges or your job after high school,” Wetherald said. “If you don’t have a roof over your head, it’s pretty hard to worry about much of anything else.”

Barzola was grateful The LOFT provided a place to live, but the nature of the shelter made school challenging to focus on. Residents would come and go every day, teenagers from all walks of life lived in close quarters and police would sometimes be called to the facility.

“That really disrupted my ability to stay focused on my life. I’d just go home — go to The LOFT — and sit in the living room, and it was just pure chaos for so long,” he remembered. “When I was there it was really disruptive and hard to do school work and stay alive.”

Meet more students:

The federal McKinney-Vento Act sets the primary guidelines for how school districts must care for students experiencing homelessness. The law requires districts to have a point person for coordinating education for homeless students and to protect a student’s educational rights, like the right to enroll in school even if some paperwork is missing, and the right to stay in one school if a student moves around.

It also sets the definition for which students are considered homeless. Students who live in shelters, on the streets or in tents outside of town are included. So are the more invisible students: The majority of Central Oregon’s homeless students are doubled up, meaning they live informally and temporarily with other families, couch-surfing with friends or extended relatives.

All of those conditions create barriers. For some students, living with their family in tents or campers on public lands far outside of town makes getting to school a struggle. For others, living in a shelter with new residents every day makes for an environment too chaotic to do homework in.

“That’s resilience. To be homeless and to still be in school is one of the hardest things,” said Eliza Wilson, director of Grandma’s House, a branch of J Bar J Youth Services that shelters pregnant and parenting teens. “And to think that they actually follow through with it — because when you’re homeless, a lot of your time is spent trying to think about where you’re going to eat that day, where you’re going to get water, where you’re going to shower if you’re going to shower.”

Being doubled up can be a challenge, too. Living without a formal lease agreement means couch surfers aren’t protected by landlord-tenant laws and can be kicked out at a moment’s notice.

The instability is too much for many students. About 7.5% of the state’s homeless students drop out of school, more than twice the rate of most other student groups.

McKinney-Vento rules only provide students with academic rights — not safe housing, internet for online homework, food or any of the hundreds of other things that students don’t have to worry about if they have a stable place to live.

That’s where Central Oregon’s network of social service agencies, nonprofits and charities come into play. For many students, their connection to resources comes from the Family Access Network, a nonprofit with advocates based in schools across the region.

Those advocates pick up where teachers leave off, said Julie Lyche, the nonprofit’s executive director.

“Our teachers don’t have the capacity to have all of these community relationships and do all the education in the classroom,” Lyche said. “That’s where we walk: The FAN advocates do the basic needs part, the teachers do the education part, but they walk together with it in support of the child.”

About 13% of the youth receiving assistance are homeless, Lyche said. The nonprofit works with students and families across the spectrum of needs and strategies for helping them are as unique as the people they serve.

It might just be access to the right school supplies that makes the difference for some students. Other needs might be more complicated — FAN might assist a student in paying a friend’s parents to let them couch surf for the school year so they don’t have to live in a tent while going to school, Lyche said.

Safe and affordable housing for kids in need and access to mental health services are the two most prominent barriers for supporting houseless youth in Central Oregon, Lyche said.

The LOFT, with capacity for 12 youth and typically a waitlist of one to two months, will soon be the only shelter for young people in the region, according to program manager Maggie Wells.

FAN advocates focus on eliminating non-school barriers and clearing a path to a high school diploma. But less tangibly, FAN advocates can also be just that — advocates.

A relationship between a student and a caring adult — a teacher, an advocate, a coach, an educational assistant — is what experts across the spectrum say is critical to a student’s academic success.

“The connection to at least one caring adult is absolutely essential to help the kids feel cared for, like they belong, that they matter, that they have equal value, that they’re not less than, and that they’re loved and cared for is by far our best and most important strategy,” said David Burke, director of secondary programs in the Redmond School District.

Burke’s district had one of the highest graduation rates for homeless students in 2019-2020, though rates still vary between district schools. Burke doesn’t point to a specific program, policy or resource that’s most important for increasing that rate.

He says an explicit focus on students who aren’t on track is part of the district’s culture, and he credits FAN advocates and other district staff who consistently point out places to serve them.

“It’s not like we’ve got anything magic going on, but I do think that we’ve baked it into part of our systems,” Burke said. “Principals know every single one of those kids by name, what their strengths are and what their needs are.”

Schools don’t have much choice other than to do the best they can for students’ educational and personal needs, said Bend-La Pine Superintendent Steve Cook — especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has forced families into more challenging circumstances, widened student success gaps in schools and added mask enforcement to teachers’ already long list of tasks.

“You are prepared for anything as an educator,” Cook said. “There’s not a luxury, if you will, of saying ‘this is our line, that’s on you guys, we’re just not going to deal with that.’”

Read about responses:

Barzola, now a freshman studying theater arts at Southern Oregon University, often recounts the time he spent homeless by remembering the people he says got him through. He lists off countless names: Friends, LOFT staff, Wetherald, a biology teacher who was willing to listen, a vice principal who went with to check him in at the shelter.

“I had a lot of people who helped keep me on track and would sit down with me every day and say like, ‘let’s do your work,’ because I just couldn’t at home,” Barzola said. “I really appreciated the support of the school. Because they were the family I needed when I didn’t have a family.”

Those connections are what made the difference for Barzola to get to graduation, to get into SOU and to get scholarships enough to pay for his first year of college.

They also made a difference for his family. He didn’t know it until his mom texted him partway through the graduation ceremony, but he was the first generation in his family to graduate high school.

“I had no idea, and that was really exciting,” Barzola said. “It had hit me. My time at Bend High is over. I’m a part of the long blue line, and I’m a part of its proud history.”