Proposal would allow Oregon paralegals to work family law, landlord-tenant cases

Published 4:00 pm Saturday, January 8, 2022

- 220109_bul_news_ak tenant cases

It’s a common story: an unmarried couple moves to Bend, has a child, and eventually, decides to separate amicably.

First, they need a custody agreement. But a retainer for a family law matter in Oregon typically runs between $3,000 and $10,000, more than either parent can afford.

Trending

Enter the paralegal, who can help people representing themselves in court file documents for a cost far less than a lawyer.

“The court documents are all there at the courthouse, but most people don’t know how to navigate them,” said Laurie Kendall, a paralegal in Bend from 2000 to 2021. “For those types of situations, where people can’t afford an attorney but they want to see their kid, a paralegal gives them the opportunity to file something with the court and at least get something started.”

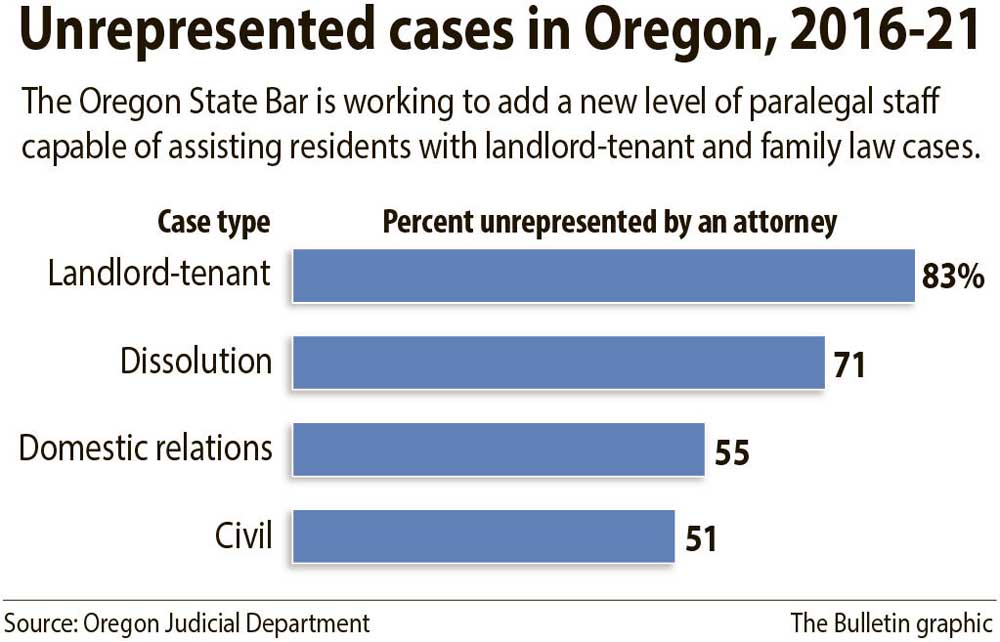

For the tens of thousands of Oregonians who represent themselves in civil matters each year, paralegals can be a guide in an often vexing legal landscape — and their wide use is prompting changes. Oregon is now on track to join other states that have addressed the growing cost of legal services by expanding the role of the paralegal through a licensing program that will expand what they are allowed to do.

A proposal by the state bar would create a new class of legal professional in Oregon — above a paralegal but below a lawyer. Think, nurse practitioner — someone who could assist clients in family law and landlord-tenant cases, two areas where many struggle to afford the cost of legal help.

Around four years ago, the governing board of the Oregon State Bar, driven by its public service mission to “advance a fair, inclusive, and accessible justice system,” launched an effort to develop a licensed paralegal program, according to a 62-page report, released in November.

The report offers a plan for implementing a paralegal licensing program, including qualification requirements and a recommended scope of work. The Oregon Supreme Court, the body that will ultimately decide whether to adopt the plan, is soliciting feedback on the proposal until Feb. 11.

Trending

“Despite the best efforts and generosity of Oregon lawyers over decades, the access-to-justice gap remains vast and largely unmoved,” the report states.

Under the bar proposal, licensed paralegals would fill new duties related to document preparation, depositions and even some courtroom representation.

The proposal contains several pathways for licensure but one constant is a minimum of 1,500 hours of “substantive paralegal experience” under the supervision of a licensed attorney. The committee additionally recommends an associate’s degree or higher in paralegal studies from a certified institution.

There are only two paralegal studies programs now in Oregon: at Umpqua Community College and Portland Community College.

The report assumes licensed paralegals will charge a much lower rate than attorneys typically do for routine family law and landlord-tenant matters: around $60 to $100 per hour compared to $200 to $300 per hour. A licensed paralegal program could also have a greater benefit in rural Oregon, where there are fewer attorneys, and licensed paralegals could potentially provide a middle ground in terms of price and availability.

The bar was motivated by reports like the 2018 Barriers to Justice study, which found a majority of people involved in civil cases (84%) could not retain a lawyer, and that racial minorities in Oregon are involved in a disproportionally high percentage of legal cases. Additionally, more than 70% of divorces involved at least one self-represented party, and only about 17 percent of parties in residential eviction proceedings were represented by lawyers. These factors are said to put strain on the courts, further inequality and erode the public’s trust in the legal system.

According to feedback so far received, the plan is popular with judges and courthouse workers, who would potentially benefit by having trained professionals assisting people who approach the court system with family law and landlord-tenant issues.

But a number of attorneys have opposed the plan, according to Kirsten Thompson, chairwoman of the Paraprofessional Licensure Implementation Committee, which developed the proposal.

“Like most new ideas, this new idea has experienced some friction,” Thompson told The Bulletin. “But we think over time licensed paralegals will become one more way that people are able to obtain legal services and will expand access to justice for some folks who just aren’t being served by the legal community at this time.”

Thompson, a retired Washington County circuit court judge, said attorneys have expressed concern about adequate training and supervision for licensed paralegals, as well as consumer protection, specifically, insurance requirements. Some lawyers have expressed a general concern that licensed paralegals would compete with attorneys.

To address these concerns, the bar would have applicants make a character and fitness application, as attorneys are required to do. Malpractice coverage and continuing legal education would also be required. As to competition, Thompson said, “The folks who are most likely to make a decision to hire a paralegal are those who can’t afford to hire attorneys.”

Laurie Kendall became a paralegal after going through a divorce and seeing that many court documents were manageable for non-attorneys. Law was also a relatively stable industry that offered her plenty of room to grow, she said.

“I never wanted to become an attorney, but the opportunity to have your own business on the side and help people, has been great,” she said.

She supports the bar proposal because she thinks it could give people without access to legal representation more freedom in determining what happens in their lives.

Oregon is not alone in developing a new legal license to address the unaffordability, and the implementation committee took much guidance from other states. Utah and Arizona have limited-scope license programs. California and Minnesota are in roughly the same stage of the development process as Oregon.

Washington began a similar program in 2015, creating a Limited License Legal Technician. The program was successful in expanding access to justice, but vocal opposition from attorneys in the Washington State Bar Association ultimately undid the project, according to a study by Stanford Law School researchers.

In 2020, the Washington Supreme Court recently voted to sunset the program in 2022.

In Oregon, the fact that in less than two years, the committee drafted a proposal that stands a chance to significantly alter the legal system in the state, is notable, said Dan Harris, retired judge and vice-chairman of the implementation committee. But a lot of that is timing, he said.

“I don’t know if it would have succeeded five or 10 years ago,” he said. “Unfortunately, demand continues to grow.”

The Oregon Supreme Court is expected to vote on adopting the plan in April. If approved, Harris said the licensing program could be in place by summer.