Oregon hits roughest stretch of omicron wave as virus recedes in much of the nation

Published 6:00 pm Sunday, January 23, 2022

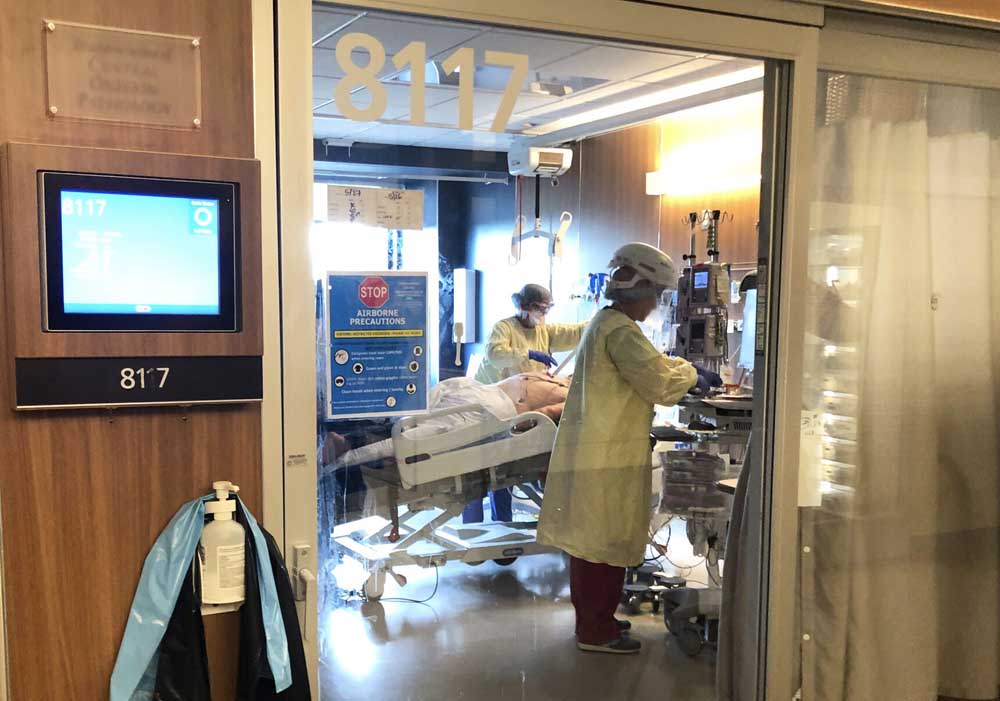

- St. Charles Bend nurses have voted to ratify a new contract with the health system. In this May 2021 file photo, nurses in the St. Charles Bend intensive care unit treat a COVID-19 patient.

The hypercontagious omicron variant of COVID-19 continues to sweep across Oregon even as it sharply declines in parts of the nation hit earlier in the wave of infections.

Oregon is coming into the two-week peak of hospitalizations and absenteeism that will hobble medical staff, police, fire departments, schools, businesses and transport. Hospitals will face a major influx of new patients before the wave’s number of severe cases peaks early next month.

“If people can stick with it for another couple of weeks, it will help to ensure timely care for everyone who needs a hospital bed,” Peter Graven, director of the Oregon Health & Science University Office of Advanced Analytics, said Friday.

The Oregon Health Authority issued its weekend report on Monday, which covers COVID-19 reports Friday through Sunday. It showed 19,400 new cases and 17 deaths statewide over the three days.

As of Sunday night, there were 1,045 COVID-19 positive patients in the state’s hospitals, down from the 1,091 reported on Thursday. COVID-19 cases accounted for 161 patients in intensive care unit beds on Sunday, up 17 from Thursday. The positive test rate remained at a highly elevated 22.9% The positive test rate needs to be under 5% to control spread, OHA has said.

Daily numbers fluctuate, but are forecast to rise this week to a peak level of 1,533 people hospitalized with COVID-19 on Feb. 1, according to Graven.

The ray of hope is that Oregon is at the end of the nationwide wave, and evidence from around the country indicates omicron levels drop rapidly after cresting. While by far the most contagious version of COVID-19 seen since the virus was first reported in China on Dec. 31, 2019, it was less virulent in individual cases of those who had been vaccinated and received a booster shot recommended late last year.

The World Health Organization said Monday that it had enough solid data to believe there was “plausible hope for stabilization” of the omicron variant.

An east-to-west spread across the United States showed a wave-like rise and fall. Omicron-driven infections and hospitalizations were reported Monday as rapidly dropping in areas of the nation where the variant first hit.

An ongoing New York Times survey of state and local health agencies showed the rate of infection had dropped 66% in New York compared to two weeks ago. Florida has seen cases decline 36%.

Hospitalizations over the same period have slowed as well. The number of COVID-19 patients in hospitals nationwide was 157,429 on Jan. 22, according to the New York Times survey. That was up a relatively slow 18% from two weeks earlier. Like infections, there were wide regional differences, with Maryland reporting a drop of 17%, while New York was down 3%.

Omicron was rising fastest in states in the West and Midwest that had seen relatively slower rates of growth. Idaho, which had been at or near the bottom of new infection reports, was up 174% the past two weeks. Oregon was up 71%.

Montana had the highest rate of new hospitalizations, up 93% over the past two weeks. Idaho was up 67%, just ahead of Oregon at 65%.

The New York Times survey showed the five Oregon counties with the highest rate of infections per 100,000 people were Jefferson, Deschutes, Umatilla, Crook and Morrow counties. The five counties with the highest per-capita hospitalizations were Jackson, Josephine, Lake, Jefferson and Baker counties.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported earlier this month that initial studies showed omicron was 90% less likely to cause death in all those infected than the delta variant. Unvaccinated people were four times more likely to become infected with the omicron variant than vaccinated people. The infection rate for vaccinated people has risen with omicron compared to earlier waves, but the outcomes of infections have been starkly different. Unvaccinated people who were infected were 10 times more likely to die than vaccinated people.