Criminal cases among those ‘mentally unfit’ have doubled in Deschutes County, straining limited resources

Published 5:45 am Tuesday, February 28, 2023

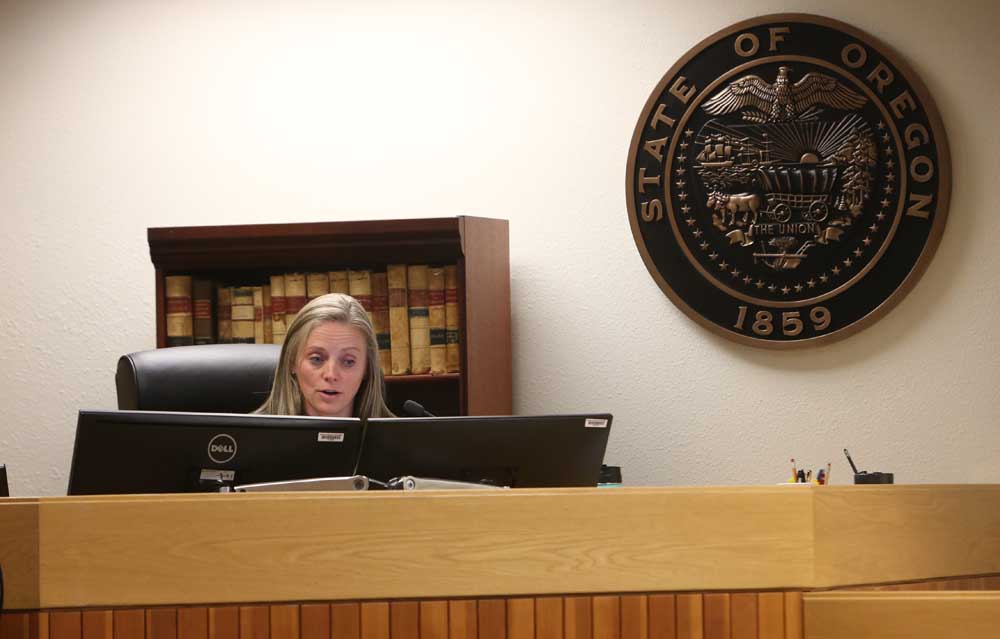

- Deschutes County Circuit Court Judge Alison M. Emerson presides over a hearing Wednesday in Deschutes County Circuit Court in Bend.

The number of criminal defendants in Deschutes County deemed mentally unfit to aid in their own defense has more than doubled since 2021, heightening concerns among local officials as Oregon faces a spike in mental illness in the pandemic’s wake.

The surge echoes statewide trends as the Oregon State Hospital, struggling with meager resources, releases a larger number of people under an August federal court order from U.S. District Judge Michael Mosman.

Trending

The order came as a result of a lawsuit against the state aimed at helping people languishing in Oregon’s jails.

By cycling people out of the hospital more quickly, the order intends to get people who are unable to aid and assist in their defense out of the jail and into treatment sooner.

But now, defendants are being released to Central Oregon communities that largely lack the means — housing and other support services — to help a defendant’s mental health improve enough for the case to move forward, experts say.

With nowhere to go, they are sometimes released out to the street, only to commit a crime and end up back in the criminal justice system.

“For some of them, it feels like you’re just waiting for them to pick up a charge to start the process over again,” said Deschutes County Circuit Court Judge Alison Emerson, who presides over a docket that includes aid-and-assist cases, “which is really counterintuitive for what we’d want to do. It’s really sad to me. I feel like these are humanitarian issues, and we’re not giving people the ability to live their best life.”

When people are considered unable to aid and assist in their criminal case, they cannot move toward a trial or settlement until their mental health issues improve enough for them to work with a defense attorney.

Trending

Currently, more than 60% of these cases in Deschutes County involve people charged with felonies; 42% are person crimes; 28% are property crimes; and 19% are motor vehicle crimes like driving drunk.

Officials say many of the people caught in this system struggle with substance abuse or experience homelessness. “A lot of them have more than one case pending,” Emerson said.

As the court waits for the person’s health to improve, the defendant is sent to different facilities. In Deschutes County, roughly half go to the Oregon State Hospital. Just over a third get local services.

About 11% go to the jail, forcing corrections staff to take on the duties of mental health treatment workers.

“Our jail is unbelievably compassionate, and they have managed a couple cases where it’s shocking to me that the jail was able to provide the level of service they were able to provide, like changing diapers,” Emerson said.

However, officials say that people with mental illness struggle to make progress in jail, prompting county officials to implement a rapid evaluation process to move people out of the jail sooner.

“The jail is the worst place for these people to be,” said Evan Namkung, the Intensive Forensic Services Supervisor for Deschutes County Behavioral Health.

Namkung said it’s difficult for people struggling with mental illness to make plans and find any sense of stability if their lives are wrapped up in the criminal justice system.

The process is difficult for crime victims, who must wait an unknown amount of time to see justice for the crimes committed against them, officials say. And it’s costly for taxpayers, involving many different entities spending large amounts of time getting a person healthy in order for the case to continue.

Joel Wirtz, the executive director of the public defense nonprofit Deschutes Defenders, said a day at the Oregon State Hospital can cost upwards of $1,200. “The way we’re doing it right now is not cost-effective,” he said.

In some cases, the defendant is well-known to mental health professionals. But because of Oregon’s limited statute for civil commitment — the process by which people are forced to receive mental health treatment because they are dangerous — they often are not required to receive treatment in a facility, officials say.

Therefore, officials say they are left waiting until a person commits a crime for them to be required to receive treatment. Some officials argue that the inability to commit people to the treatment they need is driving up the number of aid-and-assist cases.

“This is a system we’ve created,” said Wirtz. “We’ve reduced civil commitments; we’re victimizing our entire community, and we’re not helping the mentally ill. That’s why we have a bunch of aid-and-assist cases.”

One step Oregon could take is allocating funds toward building local mental health treatment facilities, so people aren’t shipped in and out of a state hospital or jail.

“We don’t have the resources in terms of residential treatment facilities,” Namkung said, noting that the county previously put people in motels when they were released from the state hospital.

Now, the Oregon Health Authority is allocating funds under Measure 110, Oregon’s drug decriminalization law, to address this issue, Namkung said. “But facilities like that aren’t just built overnight.”