Harney County judge rejects state push to strike parts of his ruling that found gun control Measure 114 violates Oregon Constitution

Published 5:03 pm Wednesday, January 3, 2024

- A Harney County judge on Tuesday denied the state's objections in his ruling that found the voter-approved gun-control measure 114 from becoming law. The state said it will appeal Judge Robert S. Raschio's decision to the Oregon Court of Appeals.

A Harney County judge Tuesday denied each of the state’s objections to his findings that helped form his opinion that Oregon’s voter-approved gun control Measure 114 violates the state constitution’s right to bear arms.

Circuit Judge Robert S. Raschio held a hearing by video to allow the state’s lawyers to make their arguments, but then systematically rejected their challenges.

Trending

Raschio will now sign a final order striking down Measure 114. The state plans to appeal to the Oregon Court of Appeals.

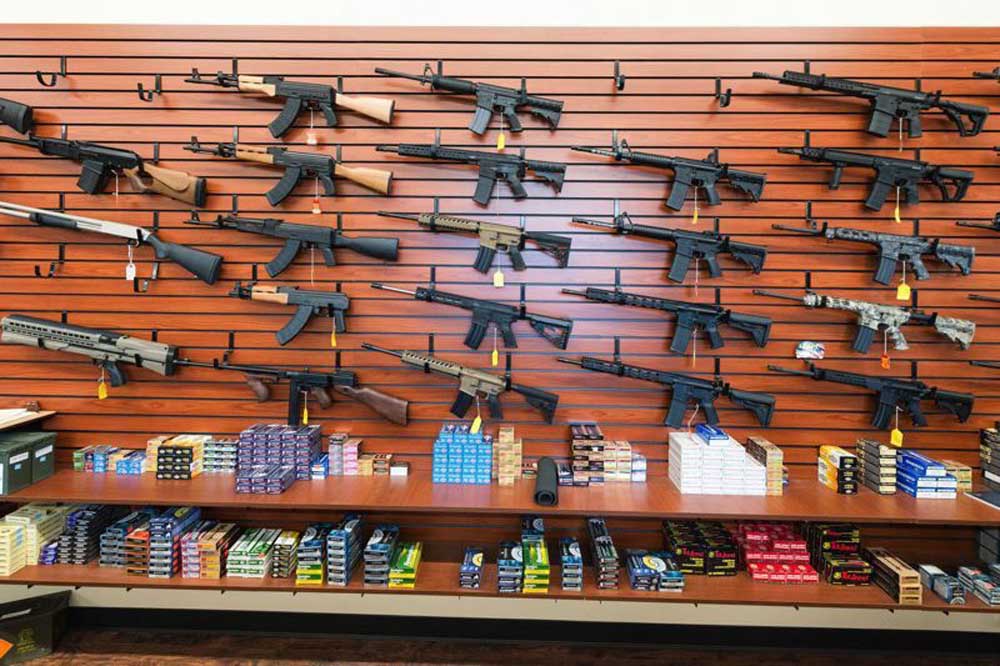

The measure, which voters passed with 50.7% of the vote in November 2022, requires a permit to buy a gun and bars the sale, transfer and manufacture of magazines holding more than 10 rounds of ammunition.

Oregon Special Assistant Attorney General Harry B. Wilson told Raschio that the state is going ahead with plans to budget money and buy fingerprint scanners should the Appeals Court overturn his ruling and allow the regulations to take effect.

Wilson said while Raschio’s ruling bars the state from enforcing Measure 114, it shouldn’t prohibit the state from “engaging in ordinary work” in the meantime to support the regulations.

Attorney Tony Aiello Jr., representing two Harney County gun owners who successfully fought the measure in court, said the state’s actions would amount to “a waste of taxpayer money.”

The judge said he wasn’t going to rule beyond finding that the measure and “all its applications” are unconstitutional under the Oregon Constitution.

Trending

“I’m not going to try to project into the future what that looks like,” Raschio said.

Despite multiple objections by the state to the judge’s findings in his November opinion, the judge stood by his ruling that the FBI won’t conduct fingerprint-based criminal background checks required for permits to buy a gun under the measure, even though the FBI’s stance had changed before the judge issued the ruling.

He also didn’t alter his ruling that the permitting process could delay a gun purchase for a minimum of 30 days, even though the measure says a permit “shall be” issued within 30 days should no problems arise during a background check.

Raschio further stood by his finding that the state had failed to present evidence that the measure would improve public safety, reiterating that the number of mass shootings in the country is “statistically insignificant” and that the evidence the state was barred from offering at trial was “not directed at the question of public safety but rather to inflame.”

Raschio wouldn’t let the state’s lawyers present the testimony of people whose family members had been killed by mass shooters in Oregon. Wilson argued to the court: “The Court excluded the very evidence it now faults defendants for failing to present.”

The judge also rebuffed the state’s objections to his conclusions that the media sensationalizes mass shootings and that gun magazines are a “necessary component of a firearm.”

Lawyers for the state had argued that there was no evidence submitted during the trial about media coverage of mass shootings and no basis for such a finding.

Raschio said he came to his conclusion “based on the record in front” of him.

He said he’ll consider whether to order the state to pay Aiello’s fees for the time he took to prepare responses to the state’s objections.

Wilson said the state’s objections to Raschio’s findings were “brought in good faith” in an attempt to have the judge reconsider them.

“We understand the court disagreed with that,” but there’s no basis for attorney fees under any law or rule in Oregon, Wilson argued.

Aiello countered that the state’s additional filing detailing the FBI’s updated stance on its handling of fingerprint-based background checks after the judge had ordered the case record closed violated the court’s order.

In a civil case, the court can award reasonable attorney fees to a prevailing party if the court finds that the other party to the case “willfully disobeyed a court order or that there was no objectively reasonable basis for asserting the claim, defense or ground for appeal.”

According to Wilson, the state had an obligation to inform the plaintiffs of the change in the FBI’s position before the close of the case.

At the time of trial, the FBI refused to allow state police access to its fingerprint-based criminal history data. Before Raschio issued his ruling on the measure, the state Attorney General’s Office worked out a temporary fix with the FBI, according to court records.

The FBI offered a “grace period” that would grant Oregon State Police access to the FBI’s national fingerprint database to complete the background checks, as long as state police agree not to let anyone other than a local police chief, a county sheriff or one of their subordinate officers access the information.

Under the measure’s language, a local police chief, sheriff or “their designee” may serve as the “permitting agent” to obtain an applicant’s fingerprints.

Raschio asked the state’s lawyers why they didn’t try to reopen or clarify the court record when it filed the additional information on the FBI’s stance.

“We didn’t think it was a live issue for trial, at all,” said Anit Jindal, another lawyer representing the state.

Whether the FBI would allow the fingerprint checks to proceed shouldn’t have impacted the judge’s ruling to determine if the text of the measure was constitutional, the state’s lawyers argued.

Raschio responded, “Then, why file anything at all?”

“We thought we had some sort of obligation to update plaintiff’s counsel about that issue,” Jindal said.