Seeing the ghostly beauty of U.S. Highway 97 north of Bend

Published 6:30 am Friday, February 23, 2024

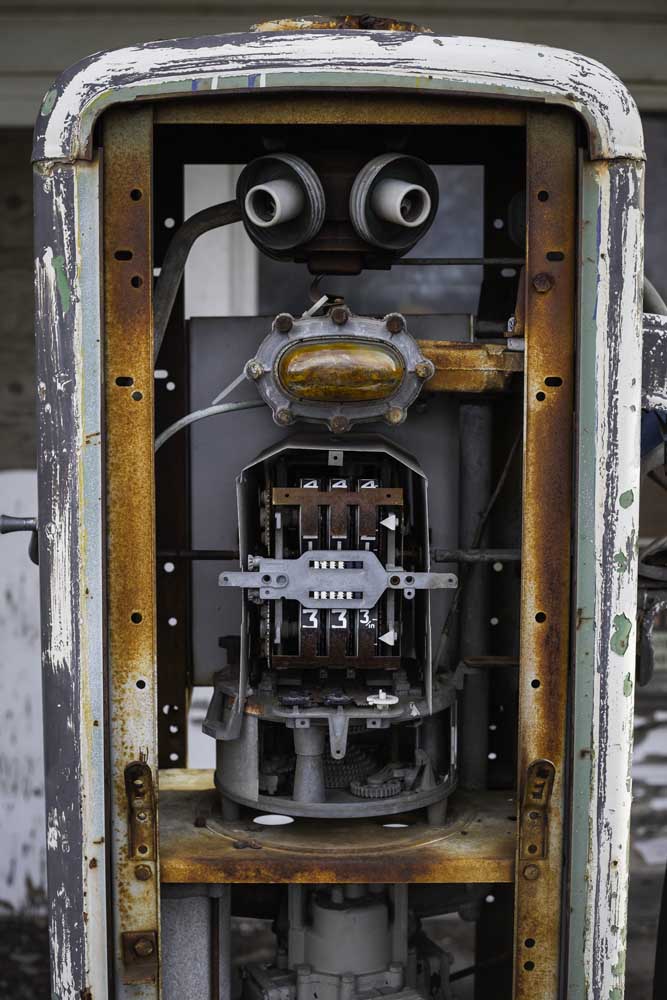

- One of two gas pumps outside the old Kent service station. Both are now missing their front and back panels offering a chance to look at the inner workings of vintage pumps.

I rarely find myself traveling up U.S. Highway 97 to Biggs. When I do, I don’t have much time to stop and take in the area that surrounds this long stretch of highway that splits the state down the middle. At first glance, driving north from Central Oregon, the route seems to offer few points of interest besides a few quaint, small towns and miles of stark, treeless rolling fields of sage, grass and windmills along the way.

But looking a little further beyond your dashboard, you will find a quiet, wondrous beauty among the seas of brush and wheat, relics of the past that still stand, sometimes rusting, deteriorating, or fading into our state’s history.

The 136-mile ribbon of asphalt from Bend to the Columbia River offers a chance to see ghost towns and abandoned buildings juxtaposed against the modernity that brings brilliant backdrops to both budding and professional photographers whether you sport the latest mirrorless camera or just click with your iPhone.

For me, having recently upgraded my camera, I had been looking forward to playing around with it on this route for a while, snapping one of my favorite “ghost” towns of Shaniko and finally getting a shot of the infamous (in Oregon scenic photography circles anyway) Orange Crush Gas Station in Kent.

Shaniko and the sheep

This part of the state is home to an abundance of abandoned buildings and formerly booming communities quieted in the early 20th century. Europeans settled in the area in the mid-19th century, and thanks to the arid climate, a handful of homesteads and buildings endure.

Shaniko is one of two towns along this highway given the “ghost” moniker by various publications and the Secretary of State Office website, which has a great rundown of Oregon’s entries with that distinction. Many of these places still have people living there, albeit small populations, making the spooky qualifier seem premature.

Shaniko is possibly the most famous of these ghost towns. It lies about an hour north of Terrebonne in northern Wasco County. The town is more of a pit stop for tourists these days than the bustling center of the sheep industry at the turn of the 20th century. Now a few shops open seasonally for travelers to grab a bite at the cafe, peruse the small museum or just walk the wooden boardwalks of the community.

Once named the “wool capital of the world,” Shaniko was also the southern terminus of the Columbia Southern Railway. Shepherds could easily transport their wool up to the Columbia, from where it could be shipped anywhere in the world.

But it was a short-lived boom. In 1911, the Central Oregon Trunk Railroad opened to the west traveling from the Columbia down to a fledgling Bend, taking businesses with it. This, coupled with an overall shift away from wool, began to shrink Shaniko.

Today, the sleepy town along the side of the highway is ripe with rustic charm and a brilliant backdrop for photographs, from the red-bricked hotel that reopened last year and also hosts the aforementioned cafe, to the long barn emblazoned with the town name wide enough to see at a wide distance.

Kent’s crush and Wasco’s windmills

The highway leads out of Wasco County and right into Sherman, the second least-populated county in the state. It is vast, trading Wasco County’s seas of sage for miles and miles of grasses covering low hills that stretch far beyond the pavement.

Kent, the second “ghost” town on this road, rises far in the distance, a spot of trees and gray grain elevators breaking the plains-like terrain. There is no limited speed in this area, and if you blink, you’ll miss what’s left of Kent, whose population has dwindled from a peak of 250 in 1905 to 67 in 2018.

Along the road is the famous former gas station, one of the more photographed abandoned buildings in the state thanks to its location along a main highway. You can park along a side street and walk right up to its rusty, open-front pumps and the flaking facade that boasts the iconic Orange Crush sign up top.

Reclaim the Sunday drive on Paulina Highway

But the famous soda pop-topped station is not the only thing to snap a photo of here. The towering grain elevators stand out starkly against the relatively flat, grassy landscape surrounding it as well as a handful more abandoned buildings. They are still in use today and there are many homes around them so be considerate if you stop.

Further up the highway, you’ll pass through the communities of Grass Valley and Moro, the county seat. They are both quiet but very much still alive, avoiding the “ghost town” tags of the previous towns. Moro is also home to the Sherman County Historical Museum, worth a stop when it’s open.

Here, the landscape adds something far more modern: windmills.

The small town of Wasco lies about a mile to the east on the highway and is the quiet county’s second-largest town. The community breaks up the amber-colored fields with tree-lined streets and ruddy brick buildings, some with their original painted signage fading from 150 years of sun beating down.

The town was built on agriculture, and now alongside wheat and grasses, they’re also harvesting wind. Just beyond the town boundaries are miles and miles of wind farms turning gusts into power. The sight of these 400-foot-high turbines is impressive enough, but coupled with the sheer number of them stretching through the fields here, they’re awe-inspiring.

Biggs and back again

Highway 97 continues from here through a creek-cut canyon that rises suddenly from the rolling hills before abruptly ending at Biggs Junction on the Columbia River. Here, travelers can refill their tanks if needed or grab a bite before venturing back down the highway and experiencing these rusty and weather-worn buildings and places again — this time in a whole new light.