A neglected Marx Brother and an unsung Stooge finally get their due

Published 11:41 am Friday, October 18, 2024

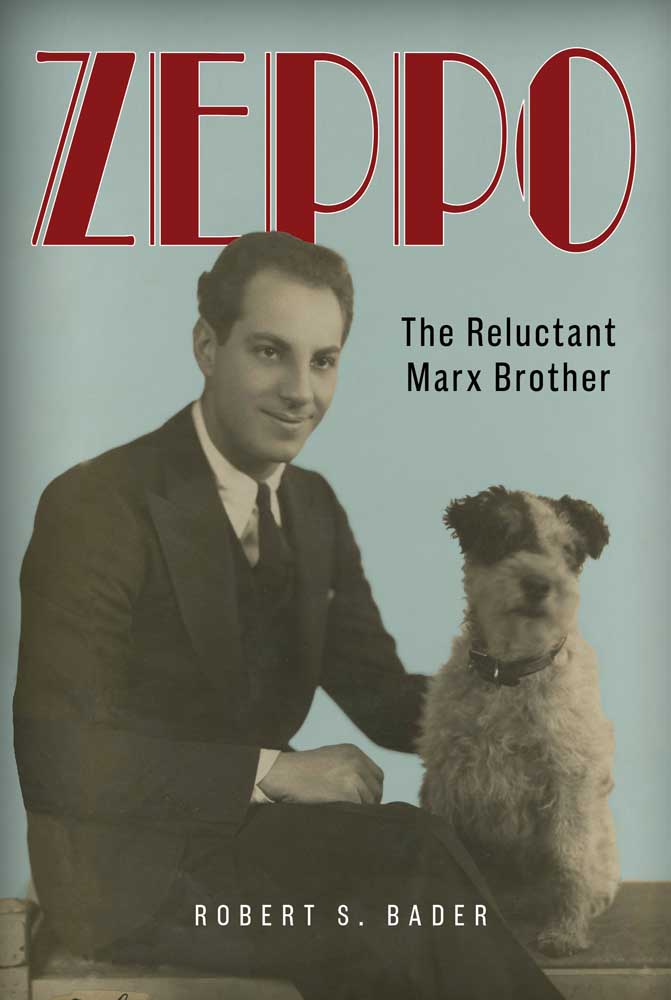

- The cover of "Zeppo: The Reluctant Marx Brother."

This month sees the release of two biographies, one devoted to Shemp Howard of the Three Stooges, and the other to Zeppo Marx of the Marx Brothers.

The casual observer may be forgiven if they are moved to ask if this is some kind of joke.

Absolutely not, says Burt Kearns, author of “Shemp!” “Of all the great comedy performers of the 20th century, few have been as shortchanged by history as Shemp Howard,” he said during a recent interview, “and much of that is due to the deliberate mythologizing of the Three Stooges trinity of Moe, Larry and Curly — at Shemp’s expense.”

Dana Gould gets it. For the comedian and vintage-show-business savant, it was Shemp all along.

“From the jump, I preferred Shemp to Curly,” he said in an interview. “I grew up with four older brothers, and they all loved Curly. Being the little brother, you always gravitate toward the one that doesn’t get the most attention. Shemp’s name was weird, but he didn’t have Curly’s shtick. I liked the fact that he looked normal but was clearly unhinged, which is funnier to me.”

“Shemp!” is not revisionist history that elevates its subject at the expense of his younger brothers, Moe and Curly. Kearns, who has written biographies of Marlon Brando and B-movie tough guy Lawrence Tierney, merely corrects the record, which heretofore was mostly defined by Moe Howard’s admittedly entertaining print-the-legend autobiography.

Born Schmuel Horwitz in 1895 to Jewish Lithuanian immigrants, the man who would be Shemp, courtesy of his thick-accented mother’s mispronunciation of his nickname, Sam, was initially the star, with Moe and Larry Fine, of a vaudeville act born out of their stint with Ted Healy, who originated the slap-happy role Moe would later play. It was Curly who replaced Shemp when he went solo after a salary dispute with Healy.

Unlike the other Stooges, Shemp had a prolific career as a journeyman actor, starring in his own shorts (available on YouTube) as well as playing supporting roles opposite Abbott and Costello, W.C. Fields, and even John Wayne. “Shemp was talented in a way that was different from the other Stooges. It’s hard to imagine Larry or Curly being anything other than Stooges,” Kearns writes.

One of many moves that made Shemp a real “mensch,” according to Kearns, is that he returned to the fold after Curly suffered a debilitating stroke.

Shemp sacrificed “his future for the thankless job of replacing his ailing brother,” Kearns said, “agreeing to keep the brand alive so his ungrateful brother Moe wouldn’t be thrown out of work.”

In the book, Kearns quotes GQ writer Mike Flaherty, who once wrote: “In the world of professional wrestling, agreeing to lose a match for the greater dramatic good is called ‘doing the job’ and considered the most honorable of gestures. … Shemp is the original jobber.”

Shemp died in 1955, but he lives on not just in his solo and Stooges work, but also in the term “Fake Shemp,” industry slang for the practice of using a stand-in for a deceased or otherwise unavailable actor. (See the Stooges short “Scheming Schemers,” which was completed after Shemp’s death and features “fake Shemp” Joe Palma.)

As for Zeppo, it must be acknowledged that the five films he made with his older brothers for Paramount are among the team’s best and the funniest ever made (“Duck Soup” was inducted into the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry).

But his legacy is problematic. His name, Robert S. Bader writes in “Zeppo: The Reluctant Marx Brother,” is comic shorthand for being “useless, unfunny or expendable.”

As recently as last month, Stephen Colbert joked in his “Late Night” monologue, in reference to Donald Trump calling Kamala Harris a Marxist during their debate: “It’s her, Groucho, Harpo, Chico and Zeppo, the most terrible Marxist of all.”

Bader, author of the definitive “Four of the Three Musketeers: The Marx Brothers on Stage” and editor of Susan Fleming Marx’s posthumously released memoir, “Speaking of Harpo,” does not make the case that Zeppo is underappreciated. “I’d say he was underutilized,” he said in a recent interview. “The least successful of his many careers was as the fourth Marx Brother. He was anxious to leave the act for years before he finally did. Zeppo was a very funny guy, but he never had a chance to be a comedian while working with his brothers. So, he just left and made more money than all of them.”

Zeppo’s resignation letter to Groucho (“I’m sick and tired of being a stooge”) comes at about the halfway point of Bader’s revelatory biography, which tells you something about the full life that followed.

Zeppo’s story comprises vaudeville, the golden age of Hollywood (as a talent agent, he represented Barbara Stanwyck, Fred MacMurray and others), organized crime (like brother Chico, he was an inveterate gambler) and even the tabloids (his second wife, Barbara, would later marry Frank Sinatra).

“I’m pretty sure he had the most unusual and interesting life of any of the Marx Brothers,” Bader writes. “Zeppo’s life played out like an adventure story featuring a very restless hero — or antihero, depending on your sensibilities. Being pushed into show business probably saved Zeppo’s life. His best friends from his teen years in Chicago spent much of their adult lives in prison, and one of them was killed in a police raid. He was on that path when vaudeville interrupted his burgeoning life of crime on the streets of Chicago.”

Marx Brothers lore has it that Zeppo was actually the funniest of the bunch. There is at least anecdotal evidence here that the zaniness gene was strong in him. Bader writes of a gin rummy game at a club during which Zeppo drew gin, but rather than call it, he excused himself to make a phone call. At that point, he rang the club, paged his opponent and called “Gin” over the phone.

Though Shemp and Zeppo were not the frontmen, Gould sees how important they were to their respective groups.

“Their roles were difficult,” he said. “Shemp, in my world, is like [punk rock group] the Cramps; everybody who knows what is good knows that this is good. And Zeppo is crucial to the Marx Brothers. Zeppo brought something to the group that was missing when he left. That was never more evident than the [tamer] MGM films his brothers made without him. You can quote me: Even the Corleones weren’t the same without Fredo.”

“Shemp! The Biography of the Three Stooges’ Shemp Howard, the Face of Film Comedy”

By Burt Kearns

Applause. 280 pp. $32.95

• • •

“Zeppo: The Reluctant Marx Brother”

Robert S. Bader

Applause. 368 pp. $34.95