Oregon’s data centers want a lot more electricity. Who’s going to pay? It could be you

Published 8:26 am Friday, October 18, 2024

- Power lines obscure an Amazon data center at the Port of Morrow near Boardman.

Big Tech has data centers in every part of Oregon.

Meta has your Facebook and Instagram posts stored in digital warehouses in the High Desert above Prineville, not far from Apple’s center. Oracle, LinkedIn, the social media company X and many others have large data centers in Hillsboro, some right next to farmhouses and suburban cul-de-sacs.

Trending

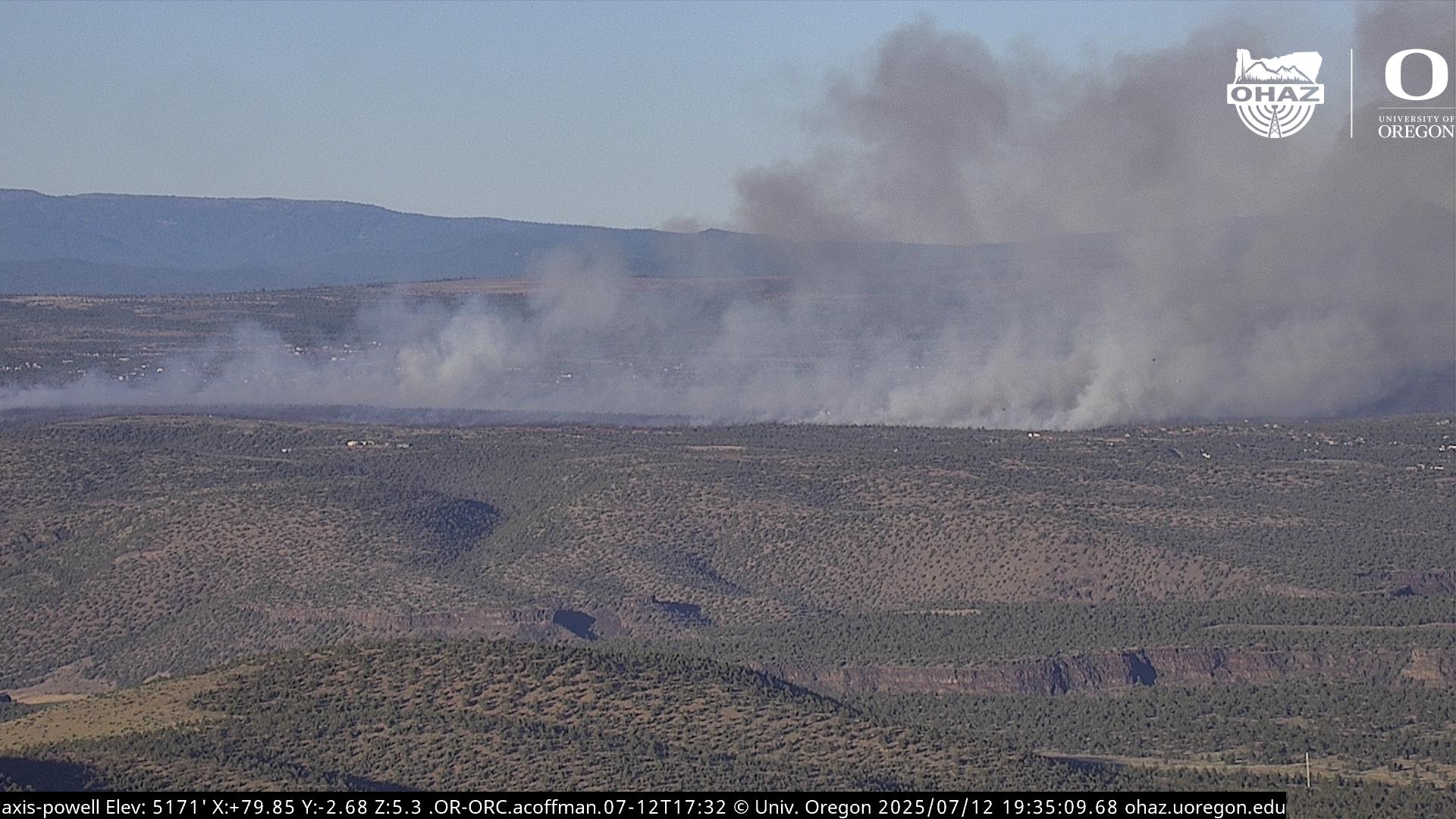

There are Amazon’s hulking concrete structures amid the fields near Boardman. And the vents billowing steam from Google’s operation on the Columbia River waterfront in The Dalles.

One thing they all have in common: Towering power lines and enormous electrical substations, providing the energy to run those high-octane computers and the systems that keep them cool.

Data centers already account for 11% of Oregon’s electricity consumption, according to industry estimates. That’s more than twice as much as all the homes in Portland.

And it’s only the beginning.

Regional energy forecasters expect data power consumption in the Northwest will certainly double by the end of the decade. Or maybe triple. Possibly, they say, it will quadruple.

With artificial intelligence requiring exponentially more energy to perform increasingly sophisticated tasks, everyone agrees Oregon is going to need a lot more electricity.

Trending

That means more power plants all over the region – solar farms, wind turbines and natural gas plants, converted from coal. Maybe, eventually, new nuclear plants, too. And it means new power lines running across the plains of eastern Oregon, over the Cascade Mountains, up through Forest Park. All told, this will cost many billions in the years to come.

Someone has to pay for it. And that’s where you come in.

Already reeling from two years of soaring household energy bills, and another big increase on tap for 2025, Oregon residents could be hit by another wave of rate hikes in the years ahead to help cover the costs of more power plants and transmission lines.

There is broad agreement — among regulators, certain lawmakers and even electric utilities —that Oregon should insulate residential electricity customers from the costs of supplying the state’s proliferating data centers with energy. But it’s not clear how to ensure the tech industry covers its own costs.

“Our regulatory structures weren’t designed for this scale of large customer growth,” said Nolan Moser, acting director of the Oregon Public Utility Commission, the state agency that regulates electric and other utilities.

In theory, he said, state regulations can assign the costs of new electrical loads to data centers and other huge industrial customers. But he said those rules haven’t faced a test like the coming wave of data center demand.

“This is not something we’ve seen over the last decades, and it does necessitate that we re-examine our approaches,” Moser said. “The world is changing and we’re going to have to deal with it.”

Adding to the complexity, forecasters say there is some chance that the rapid growth in data center power consumption could exceed — for brief periods — what the region can provide.

That could require expensive power purchases on the open market, raising rates even further — an ugly echo of the Western power crisis at the beginning of the century.

Going electric

Oregon is a relatively small state with an immense data center industry.

A report last year by the California-based Electric Power Research Institute ranked Oregon fifth nationally in terms of how much energy its data centers use. The report forecast that data centers will use more than twice as much in 2030, consuming nearly a quarter of all Oregon’s electricity by then. Some forecasters at other organizations think server farms may need even more.

The institute cited the region’s relatively low power costs, moderate climate and hydropower as reasons why Oregon is so popular with tech companies.

Oregon’s biggest draw, however, is its tax breaks, rated among the most valuable in the world for data center operators. That’s brought many of the world’s wealthiest tech companies to cash in by placing data centers in some of Oregon’s smallest communities.

The industry enjoyed property tax exemptions worth $227 million last year alone. Data centers’ savings will run in the billions of dollars in the years to come, capitalizing on a state enterprise zone incentive program designed for small manufacturers in the 1980s.

Power companies are the other big winners. Investor-owned utilities earn a fixed rate of return on new investments that expand their capacity to generate or deliver electricity. A growing market means more revenue, and more profit.

In its most recent financial report, Portland General Electric cited Hillsboro’s rapidly expanding data center industry as one of the top factors in its growth. In its latest update to state regulators, PGE said demand from industrial customers grew by nearly 11% in 2022 and another 8% in the first three months of 2023.

“The primary driver of PGE’s increased load forecast is to reflect rapid industrial growth and growing demand of data centers in PGE’s service territory,” the utility said.

In a filing this past week with state utility regulators, PGE reported that it expects Hillsboro’s data centers will use 2.2 million megawatt-hours of electricity next year. That’s nearly as much power as all the 237,000 homes in Washington County, combined.

Electricity use will grow rapidly across the Northwest, forecasters say, as artificial intelligence becomes more entrenched in work and personal applications and data centers take on new power-hungry workloads.

It’s a dramatic shift from the prior two decades, when efficiency programs and products helped keep regional electricity loads relatively stable despite sustained economic and population growth.

Consumer advocates worry the data centers’ thirst for energy will hit the pocketbooks of ordinary Oregonians, who are already facing the prospect of rates climbing as much as 50% in a two-year period.

“We’re increasingly having an affordability problem with electricity in the state already, before these data centers,” said Bob Jenks, director of the Oregon Citizens Utility Board, which advocates for utility customers.

There’s no way to know now how much of data centers’ power costs might trickle down to residential ratepayers. Forecasters are still guessing about how much power data centers will need and it’s unclear how regulators will safeguard residential customers.

Jenks said Oregon lacks strong mechanisms to protect ratepayers from picking up costs for data centers run by the world’s richest people, or to protect the profits of PacifiCorp, a utility owned by billionaire Warren Buffett’s investment firm.

“Customers are being asked to absorb the costs associated with that, residential customers, people living paycheck to paycheck,” Jenks said. “That doesn’t make rational sense.”

Data centers aren’t the only reason for the coming power surge. “Electrification” is booming as people and businesses shift away from cars, appliances, furnaces, generators and industrial equipment powered by fossil fuels. Electricity is often cheaper, and usually cleaner.

Data centers aren’t necessarily cleaner, though. They’re buying energy from wherever they can get it, and that is giving the region a bigger carbon footprint because much of that energy is still generated by fossil fuels.

The Umatilla Electric Cooperative, a tiny utility serving parts of eastern Oregon, is now among the state’s biggest carbon emitters — largely because it’s buying power generated by fossil fuels to energize Amazon’s local data centers.

Lights out?

Forecasters are growing increasingly alarmed that the Northwest may not have enough electricity of any kind to meet all the new demand.

“Over the next five years across the Pacific Northwest, significant load growth and changing system dynamics are creating risks for maintaining power system adequacy,” the Northwest Power and Conservation Council wrote in an August report.

The regional energy planning organization says the Northwest needs a lot more electricity. But its experts are flummoxed when they try to forecast just how much.

The council’s forecasters came up with four growth scenarios through 2029. Even in a “low” growth scenario, they envision Northwest data centers’ power needs will increase by 1,500 average megawatts within five years.

That’s as much power as a million homes use today.

And Northwest data centers’ growth might be much, much larger — perhaps on the order of 5,000 megawatts eventually. That’s equivalent to 4 million homes’ power use.

Which estimate is right? The council’s forecasters say they can’t tell and aren’t rating any scenario more likely than another.

“We don’t want the load forecast to have a narrow band because there is a lot of uncertainty there, so we are going to plan for a wide range of trajectories,” said Jennifer Light, the council’s director of power planning.

It all depends on how many data centers get built, whether artificial intelligence computing gets more efficient and whether the region can generate the power big computers want and then deliver it over transmission lines.

“Those data center loads are not going to show up,” Light said, “if the resources are not there.”

There’s another possibility, though. Data center loads and utilities’ capacity to serve them may both increase substantially — but perhaps not always perfectly in sync. That could lead to periods when the power companies can’t quite keep up.

The power council warns that during brief periods of especially high demand, like hot summer days and frosty winter nights, there might not be enough power to go around. The situation is complex because many new renewable power plants generate power intermittently, when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing.

The council ran simulations covering 180 hypothetical years of hot or cold temperatures, trying to forecast the impact of variations in wind and solar power. If data center electricity use hits the forecast’s upper range, the region would experience power shortages every year beginning in 2029 – most often during the winter months.

Even a brief power shortage could trigger emergency measures, forcing utilities to buy electricity on the spot market, potentially at very unappealing prices. That could send everyone’s rates soaring.

If things get really bad, the next step would be “extraordinary measures.” Public officials would call for industries and residents to voluntarily curtail their electricity consumption. Cities might turn off streetlights. Government offices might go dark. Hydropower dams would run full-tilt, abandoning protections for fish.

If those things don’t work? Then it’s lights out.

In that extreme scenario, utilities would shut off electricity to some customers for brief periods, perhaps lasting several hours. The power council didn’t forecast the chances of such an extraordinary situation, and utility regulators say they’re committed to preventing blackouts.

“For us, blackouts are not acceptable in a planning environment,” said Moser, the utility commission’s director.

“If utilities are doing their part and planning, we don’t get there,” he said. If the utilities fail, he said they could face financial penalties or other sanctions.

Who pays?

The solution is a lot more electricity, and a lot more power lines to carry it from wind farms, solar arrays or natural gas plants across the Northwest to the data center clusters around Oregon.

U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Oregon, said state and federal agencies need to work together to expedite planning for new energy infrastructure.

Transmission lines carry electricity for miles — or hundreds of miles — sometimes across or around sensitive environmental areas, difficult terrain or through urban areas. Wyden said regulators should be able to move rapidly to consider transmission routes while preserving the land the power lines run through.

“I’m of the view that it’s possible to expedite permitting without throwing the environmental laws in the trash,” Wyden said in a recent interview. “And this will be a big battle.”

The Hillsboro market is a particular focus because of Intel’s expansion plans and a growing cluster of data centers underwritten with tax breaks. Utilities are looking closely at ways to route new power lines into Washington County, focused on another major power line through Forest Park.

Power plants and major transmission conduits typically take years to plan, permit and build, but the region may not have much time. Forecasts suggest a power crunch could come within the next five years.

“This is why PGE is working so hard to get that new (transmission) line in across Forest Park, because they can see that load growth coming and they absolutely know they do not have the capacity to serve it right now,” said state Rep. Mark Gamba, D-Milwaukie. He leads a workgroup of lawmakers studying the region’s power needs on the heels of the big spike in utility rates.

Regulators and watchdogs say data centers didn’t have much role in recent price hikes. They attribute the recent increases to wildfire mitigation, inflation that affects utilities’ expenses, volatile markets for fossil fuels and the cost of Oregon’s state-mandated shift to renewable power.

As data center loads grow, even the utilities want clearer rules on who pays for the spiraling electricity demand.

“There’s no doubt that load growth from data centers and digital information technology sectors is growing. It’s growing in exceptional ways that the utility industry has not experienced before,” said Kristen Sheeran, PGE’s director of sustainability strategy and resource planning. She said more action is needed to shield consumers from the risk and costs associated with data center demand.

“It will require different regulatory mechanisms to address the cost of this load growth,” Sheeran said.

What does it all mean for your monthly power bill? It’s hard to know.

Test case

An early test case provides some reason for hope, and some for concern.

A year ago, PacifiCorp asked state regulators for permission to assign future costs associated with some new line extensions to large customers, in that case effectively increasing rates for customers using more than 25 megawatts. Existing regulations “were not designed to address the size of customer PacifiCorp is anticipating,” regulators wrote, a nod to the growing data center market.

Amazon and an organization of other large industrial customers fought PacifiCorp’s request, arguing that the plan could force them to pay more than their fair share of new costs.

Regulators ultimately ruled against Amazon and the other big electricity users. But the issue highlighted how difficult it may be to structure rates to separate residential customers and the data centers.

Even if regulators, data centers and utilities can agree that consumers shouldn’t bear the costs of these new power loads, they may not agree on how to accomplish that.

Ironically, residential customers could end up with higher bills even if data centers’ power needs are smaller than anticipated.

If utilities add capacity for anticipated data centers but those facilities aren’t built, or are more efficient than forecast, their electric bills won’t cover the cost of the construction. That could leave consumers open to footing part of the bill

PacifiCorp is currently before the utility commission in a dispute with Amazon and Meta, Facebook’s parent company, over that scenario.

Oregon could be facing years of regulatory fights with no certainty that consumers will be fully insulated from the impacts of data centers’ power demand.

“The scale, pace and uncertainty surrounding this potential load growth will require additional regulatory updates to protect all customers while creating a path for large customers to expand their businesses,” PacifiCorp spokesperson Pampi Chowdhury wrote in an email.

Google declined comment and Meta didn’t respond to inquiries. Amazon said regulators’ job is to ensure all utility customers should “pay their fair share.”

“Where we require specific infrastructure to meet our needs (such as new substations), we work to make sure that we’re covering those costs and that they aren’t being passed on to other ratepayers,” Amazon said in a written statement. “We’re also working with utilities on innovative new agreements to keep rates comparably low and bring net-new carbon-free energy projects to the grid.”

Cooperation, maybe

Tech companies’ power needs may not always conflict with consumers. Since everyone will need more electricity as data centers expand and the region moves away from fossil fuels, tech companies could help finance new energy sources and transmission lines so residential customers aren’t carrying the whole burden.

“These large customers can bring new things to the table. They can bring new generation, potentially,” said Moser, from the utility commission. And he said it’s possible that data centers — which typically operate around the clock — could shift their computer work to other regions when power is tight in the Pacific Northwest.

To date, Moser said he believes tech companies have worked with regulators in good faith — even when they disagree about how to allocate costs. And he said he hopes they can be part of the solution.

“Asking them to do more, to contribute to solving the problem, is a logical endpoint when you’re thinking about where we have to go,” Moser said.

In other ways, though, data centers are more challenging than other utility customers.

It’s a highly secretive industry. Tech companies never want competitors to know about construction or power usage plans. And in Oregon, they pit small communities against one another in pursuit of the biggest tax breaks and so they don’t want to tip their hand about what locations they are considering.

Gamba, the state representative, said power companies contribute to the uncertainty by hiding the nature of their power demand from regulators and lawmakers.

“The utilities are very careful not to allow any of us to see the data as to what percentage of the load growth is data centers, what percent of it is advanced manufacturing, what percentage of it is (electric vehicle) charge,” Gamba said. “That’s unacceptable. We need that data because we need to be able to parse who is going to pay for this load growth.”

That might require crafting new utility laws, he said, perhaps as soon as next year’s legislative session.

Gamba said the big companies need to know that Oregon ratepayers “can’t take another hit so you can have cheaper electricity. You all are going to have to pay your fair share.”

Oregon should do some soul-searching of its own, too, Gamba said. He said the state needs to review whether its enterprise zone tax breaks are accomplishing their original goals given the rise of data centers and changing makeup of the state’s industrial sector.

And Gamba said Oregon needs to figure out why it is being caught off guard by the surge of data center demand, putting ordinary ratepayers at risk, given the industry’s prominence and rapid growth over the past decade.

“So what? Everyone went to sleep and just woke up yesterday?” Gamba asked. “It’s a little frustrating that the people who are supposed to be the smartest people in the room didn’t see this coming.”