Dropping In: Jobs can weave themselves into identity

Published 12:30 pm Wednesday, December 11, 2024

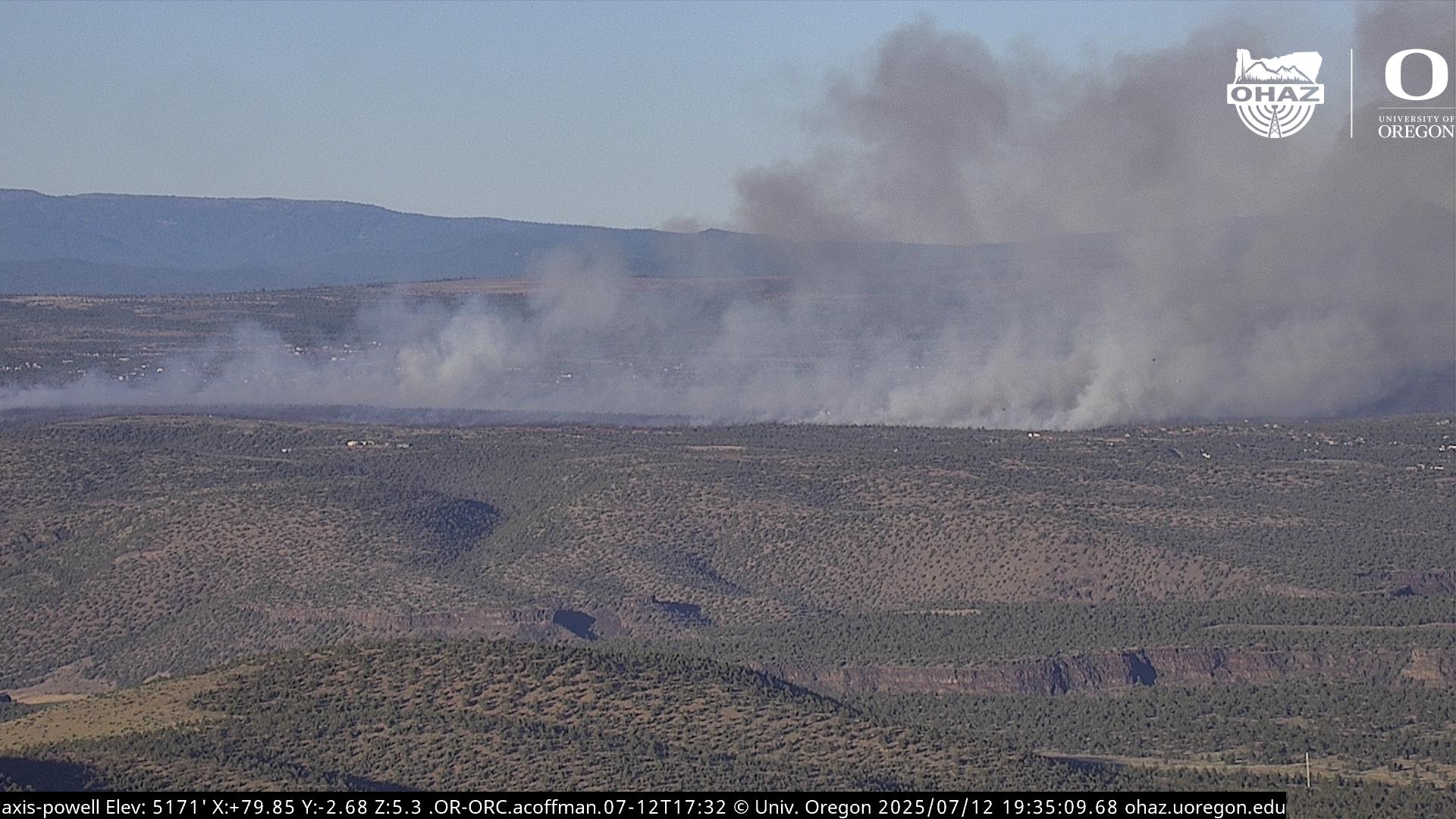

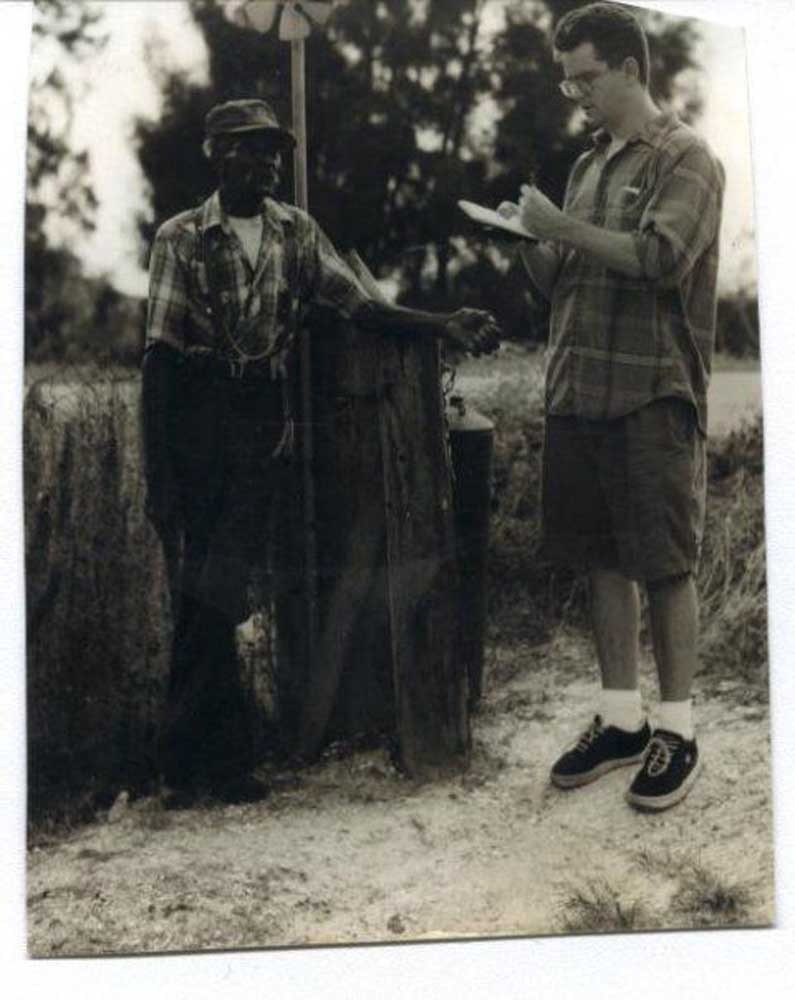

- Columnist David Jasper interviews a farmer living near the banks of Lake Okeechobee, Florida, in 1999, his second year as a features writer for Tampa alternative newspaper the Weekly Planet.

My dad had a strong sense of right and wrong, as well as a penchant for being a do-gooder, which is probably why he became a firefighter. And sometimes those Samaritan leanings kicked in when he wasn’t at work, too.

Once at a minor league baseball game in Miami, he and I were at a concession stand where we witnessed a nearby drunk guy punch a woman. I was only probably 10 or 11, but he told me to find my seat because he was going to follow the guy. I was more worried about how the heck I was going to retrace my steps to the seat than I was about the fact that my dad, a scuba diver, distance runner and weightlifter by avocation, was going to follow a violent drunk guy. I don’t know what I thought he might do, but I found my way back to my mom and sisters. When he returned to our family, he told us he’d trailed the guy to his seat, then fetched police.

Trending

Another time he was in the middle of a haircut at a mall in Philadelphia, he witnessed a purse snatching. He leaped out of his chair still wearing the apron around his neck, gave chase to the purse snatcher, who was just a teenager. He wrote about this and other adventures in his memoir-like, longhand notes shortly before he died, as I’ve mentioned in this space before.

Column: Lessons learned from my late father’s letters

“I tore off the barber’s sheet and went after him. I knew he would be faster than my 30-something legs were, but I thought I had a shot because of the crowds. No luck. He gradually pulled away and disappeared on me. The barber was perplexed because he didn’t know what it was all about.”

Imagine getting involved instantly like that. This was standard procedure for him. He lived for this kind of thing. It was no surprise he took his rescue work home with him.

Trending

In a sense, my dad remained a firefighter even in retirement. He was forced to retire at just 52 even though he was in great shape still, because the rule was age 50 or 25 years in the department. He seemed terribly on edge and probably depressed that year, but it was 1986, and no one self-diagnosed back then the way they do now.

Eventually, he settled into a groove but still seized opportunities for heroism like at the barbershop and ball game. One of those times he was driving his truck when a car ran a yellow light and hit another vehicle at a 45-degree angle. The hit-vehicle came rolling toward my dad’s truck and jammed into the driver’s side. He did construction work after firefighting and had a bunch of gear in the cab with him that blocked his access to the truck’s passenger door.

“I didn’t lose any time climbing out through the window because the car that hit me was pouring smoke from under the hood and the engine was jammed at what seemed full throttle. There was a woman driver slumped over the deflating airbag. I knew I had to get her out of there because she couldn’t move, and it looked like it could really start burning. Even in my haste, I had time to notice that all the traffic kept moving. Outside of a few gawkers, no one wanted to help or get involved.”

The injured driver’s foot was stuck in the floorboard where the engine had pushed through into the passenger compartment. She was not a small woman, and once my dad managed to dislodge her from the wreckage, he carried her to a grassy area.

“When I bent to lay her down, she began to scream in pain. I had to lie down myself with her on top of me. I thought I could then slide out from under her. When I tried to do so, she began screaming and crying again. She had a death grip around my neck and was sobbing in pain. A truck driver finally stopped and threw a blanket over us.”

The woman passed out while he was still trapped beneath her. The accident scene was only a mile from his old firehouse, so naturally, when firefighters arrived, he knew some of them.

“When my old buddy saw me lying there, he said, ‘Jasper, what the hell is going on here?’ They pulled the blankets off and saw the position we were in,” my dad wrote. “One of the group said, ‘It looks more like a party than an accident.’”

I’d never thought of it till now, but in all those stories, even that last one, the commonality was his drive to help and protect others. He later went to court to testify on the injured woman’s behalf.

I like to think that in most people who were raised by decent parents, there lurks an impulse to help others the way he did. Maybe most of us just haven’t lucked into the right situation. The closest I’ve come was maybe two or three times while bike commuting, I happened along when vehicles stalled, and I helped push them out of the way. It felt great! Plus, I helped by contributing labor without the responsibility of figuring out which way to steer. I could help like that all day.

Ok, I realize I have a long way to go to be like my dad. I wish I had that kind of moxie, that ability to quickly ascertain what’s right and get involved. Maybe discretion really is the better part of valor, and I will always lean the wrong way, toward discretion, instead of seizing the opportunity to do something heroic.

I do, however, relate to the blurring of private and professional life after decades in a career. Off the job, when I see something happen, or an idea occurs to me, I often frame things — or rather, things arrange themselves — in terms of a potential column or story.

Often, I reach for my iPhone and begin writing or dictating in the Notes app. I think that even if I were to stop being a professional journalist, part of me would always regard myself as one. Even if I were to, say, start driving a bus, I’d probably go home and write down passenger conversations I overheard.

After a while, if you do a job long enough, it’s just part of who you are.