Editorial: Oregon legislators may boost benefits for some state employees

Published 5:00 am Wednesday, February 19, 2025

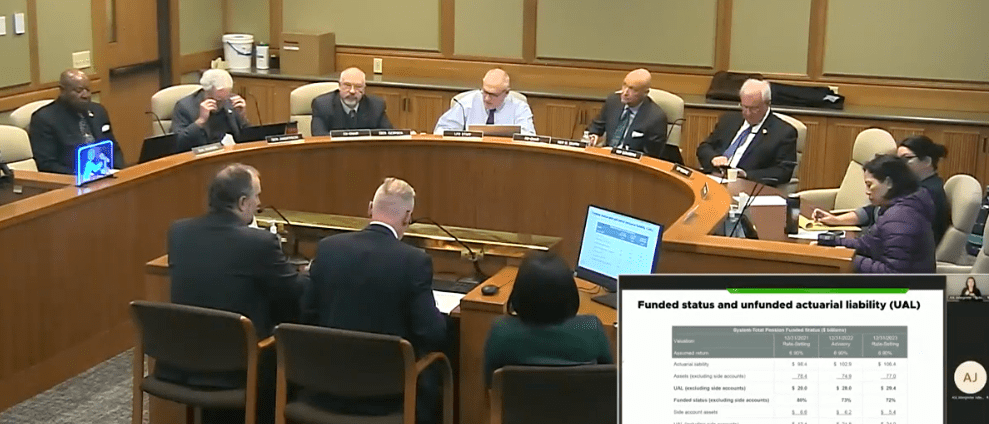

- A joint legislative subcommittee meets Monday to hear a presentation on the state's retirement plan for public employees, PERS.

If you get confused about Oregon’s Public Employees Retirement System — known as PERS — you are not alone. Even people paid to follow it can get lost in the complexity or, at least, joke about it.

“I have not learned a thing, because I am more thoroughly confused than anything else — all these numbers coming out of here,” state Sen. James Manning, D-Eugene, said Monday in the middle of a presentation about PERS to a legislative committee.

PERS is special. It is the deep water. There are billions of state dollars involved. It is the retirement program for some 400,000 people.

Most PERS retirees are not making ridiculous amounts off their pensions. The average annual benefit is $34,762. Only a tiny percentage, less than 2% or about 3,000 beneficiaries, make upward of $100,000 a year or more in benefits.

PERS has conflicting objectives. It exists to provide an important benefit for public employees. At the same time, there is a desire not to saddle future Oregonians with excessive debt or take money that should be going today to pay for roads and teachers.

On top of those things, PERS has what’s called an unfunded actuarial liability of some $24 billion. That’s one of the trickiest parts of PERS. It sounds like a deficit. It’s sometimes referred to as a deficit, but it’s more accurately defined as the difference between what’s estimated to be the future costs of retirement benefits and the assets available to pay them. So while it would be better if that number was smaller, everything could be fine even with an unfunded actual liability in the billions with careful stewardship of the program and if the stock market does well.

Everything also could be not fine. For instance, if the state investments do poorly or if legislators choose to make the benefits to state employees richer, that liability could get worse. And that could mean, in turn, that state government and entities, such as cities and school districts, have to pay more into PERS and have less money for roads or teaching.

Legislators got a review of the PERS basics on Monday. A chart showed a summary of the ebbs and flows of the conflicting objectives over the history of PERS from its beginning in 1946. Legislators enhanced PERS benefits in some years. There were cost of living adjustments, accrued sick leave was added to final benefit calculation and other changes that boosted how benefits were calculated.

There were waves of changes with reductions — in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In 2013 there was another series of reductions by the Legislature. Many of those 2013 changes were found to be unconstitutional in 2015, in a way they were found to have broken a promise. Most recently, there was an enhancement in benefits in 2024 that decreased the retirement age for some police and firefighters from 60 to 55.

Manning has a bill this session, Senate Bill 475, that may become another entry in the ebb and flow of PERS benefits and reductions. The bill changes how overtime is calculated in some PERS benefits to the advantage of employees. “Some employees do 300 hours of overtime and they are not getting credit toward PERS,” he said.

Not much has happened with his bill, yet. It is not scheduled for a committee hearing. No legislative financial analysis was available as of Tuesday morning. Will SB 475 be a change that is deserved for employees, or too much of an added burden on the $24 billion for government and taxpayers? That’s the question legislators must answer.