Editorial: The plague in Central Oregon and the value of public health

Published 2:29 pm Wednesday, April 9, 2025

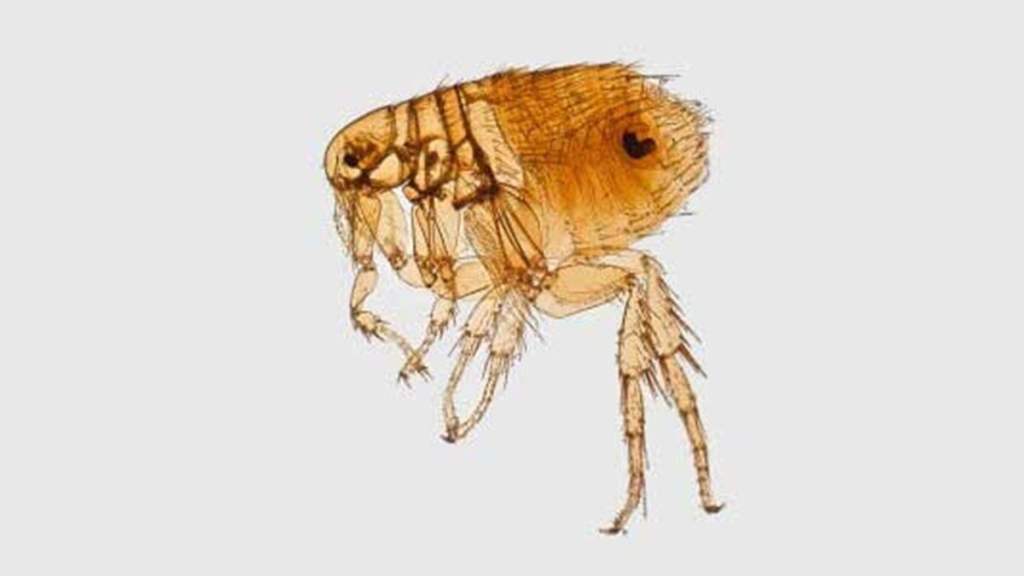

- The bacterium that causes plague can be transmitted by fleas. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

A 73-year-old man showed up in the emergency department in Redmond in January 2024. He had a skin lesion on his forearm, reddening of the skin and swelling.

The cause was not clear. He was a medical mystery.

He had other ongoing conditions, including pulmonary disease and hypertension. More recently, he had accidentally cut his right index finger with a knife.

The man had gone to urgent care for the wound on his finger. It had been sewn up with five sutures, and he got a tetanus booster. That was one day before he went to the hospital. The wound on his finger appeared to be healing well.

His cat had been at the vet about one week before he got the lesion on his arm. The cat was getting antibiotic treatment and drainage of a neck abscess. The man had brought the cat home and was draining the abscess himself – without gloves and with the wound on his finger. The cat’s wound “may have started after an unwitnessed altercation with a porcupine or raccoon,” according to a review by Deschutes County Public Health. It was not clear what happened.

When the patient arrived at the emergency department, he was experiencing chills, sweats, fatigue, nausea and got dizzy when he stood up. Many of his vital signs were normal or high normal. He had slightly elevated numbers of one test looking at his liver and his kidneys tested normal. They X-rayed his chest and did an ultrasound of his arm with the lesion. He had some blood clotting, which did not completely block the flow of blood. He was admitted to the hospital. The staff at the hospital started him on two antibiotics. They took some blood samples.

On his first hospital day, the oxygen in his blood dropped. The blood cultures taken also suggested he had bacteria in his blood, which was resistant to antibiotics. That can be serious. Hospital staff were still trying to figure out the cause.

On his second hospital day, he needed supplemental oxygen. His white blood cell count had increased, indicating his body was at work fighting.

On the third hospital day, he was seen by an infectious disease specialist. Lab testing determined that what he had was consistent with Yersinia pestis. With his other symptoms and the history of the sick cat, there were few other things it could be. Yersinia pestis is the bacteria that was the cause of the plague, the Black Death, a one-horseman apocalypse.

In proportion to population, the plague may have been the most lethal catastrophe in human history. The first strike of the plague, from 1346-1353, is estimated to have killed half the population of Western Europe. Strikes of the plague also hit Scandinavia, north Africa, the Middle East. Many people assume it also hit China in the same time period. Records are incomplete. There were later waves of the plague in the 1700s and 1800s. Those later waves were less lethal and less frequent.

It is believed there were much earlier deaths from the plague. It was found in the DNA of skeletons from around the third millennium, B.C.E.

Where did it come from? There is some research that suggests the plague originated with marmots in what is now Kyrgyzstan. It may have spread through caravans — camels, gerbils, black rats and the fleas along for the ride. Flea bites have been a method of transmission.

Once the cause was identified, the patient was put on different antibiotics. He began to improve gradually and was breathing comfortably by hospital day seven. He was discharged with some medicine to take and recovered. It’s not clear how he contracted it.

There was another problem, though, controlling any spread.

The reason there are only sporadic incidents of plague today – only 18 cases in humans in the Pacific Northwest over the past 90 years – is because of flea control, modern medicine and quarantines. Public health efforts have played a vital role.

St. Charles infection prevention notified Deschutes County Public Health that there was a patient with the plague. St. Charles tracked down members of its staff who had been in contact with the patient and ensured they got preventative treatment. The good thing was the patient was already in the hospital before the patient became especially contagious. County public health began tracking down people in the community and the cat.

The patient’s cat died on his second day in the hospital. When public health inquired about it, the cat was on the way to be cremated. That was stopped with a phone call, because it was wanted for testing. The presence of yersinia pestis was later confirmed in the cat by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Staff at the vet’s office who were exposed to the cat were identified and preventive prescriptions were called into pharmacies.

One of the people at the vet’s office was a 16-year-old girl. By the time, public health staff tracked her down, she was at Disney World on vacation with her family.

What if she had it? What if it spread from there? There was some worry.

She didn’t. Nobody at the hospital or elsewhere became infected. People who were identified as contacts were repeatedly called for a week just to be sure.

Mystery solved. Fast action. And there was no spread.

If it is proposed that we cut back on public health locally or nationally, avoid that — like the plague.