Recomposing life from bones

Published 5:00 am Friday, June 24, 2011

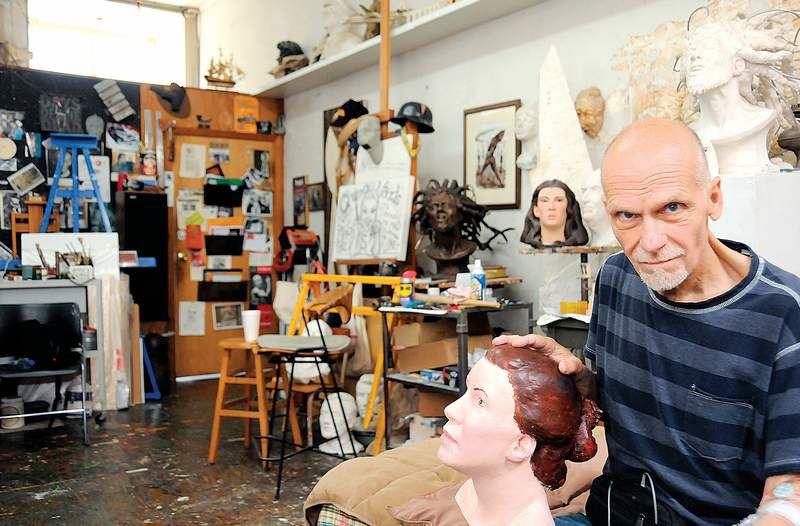

- Frank Bender, a forensic sculptor, with the bust of a homicide victim from a 2001 cold case, hopes to help authorities solve this final case. Bender, 70, has a terminal cancer of the chest cavity.

PHILADELPHIA — For decades, Frank Bender has stared at human skulls, handled them, even boiled scraps of flesh off them. He has done this to shape clay busts in the hope of giving names to rotting corpses and skeletons found in woods or alleys or abandoned houses.

He has also studied old photographs of fugitive killers, then sculptured busts embodying how they might look years later. His work has helped authorities capture several notorious criminals who may have thought they were safe in their new lives.

Trending

Now Bender, one of the most respected of a small breed of forensic sculptors, has completed one more case — trying to help investigators identify a woman whose decomposed remains were found by a deer hunter in the woods of eastern Pennsylvania in December 2001.

“Every time I work on one, it’s my favorite,” Bender said recently in his Philadelphia studio, a converted butcher shop. But this one is special.

It will be his last, and his 70th birthday, last Thursday, was almost surely his last. Bender entered hospice care this month for pleural mesothelioma, a terminal cancer of the chest cavity.

There is no indication of how or when the woman died. Thomas Crist, an anthropologist who examined the badly decomposed remains for the Northampton County coroner’s office in 2001, says she was 25 to 40 years old (most likely 30 to 35) and of European descent, though subtle characteristics of her molars also suggested an African background.

Nationwide computer searches based on dental records and the woman’s DNA failed to turn up a match. A search of missing-reports also went nowhere.

“This case has perplexed me for years,” said the county coroner, Zachary Lysek, who was a local police officer for eight years before becoming coroner in 1992. So this spring Pennsylvania investigators turned to Bender.

Trending

Crist, who teaches at Utica College in New York and has been a consultant for the Philadelphia Medical Examiner’s Office, said he greatly respects Bender’s work and is fascinated by “his insights into the detailed characteristics that make each person’s face unique.”

When Bender measures a forehead and the distance from, say, eye socket to nostril hole, he starts to see a face. From statistics and experience, he surmises how thick the tissue must have been, the shape of the nose, the fullness of the lips.

But there is more to it, as this case demonstrates.

Perhaps, a visitor suggested, the woman was a drug addict or prostitute who had dropped out of conventional society. The fact that she has been unidentified all these years pointed to such a background. Right?

Wrong, Bender said. The extensive dental work, including a root canal and crowns, suggested that she’d had resources, sophistication, self-esteem. Maybe, he said, “she got a divorce, was feeling her oats, wanted to start a new life — and met the wrong guy.”

Bender’s bust has her head tilted slightly upward, as if in aspiration, her eyes seeming to gaze at the horizon. Why, he was asked, did he leave a tiny opening between the lips, as though she was about to say something?

“I don’t know,” Bender said with a shrug. “It just works.”

Bender, who paints and has worked as a photographer, got his start in forensics by accident. In 1977, while taking evening classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, he went to the Medical Examiner’s Office for his anatomy studies.

He saw the decomposed body of a woman who had been found near the Philadelphia airport. After studying her shattered skull, he started to get a sense of what she must have looked like. So he did a bust of her.

After the bust was publicized, the woman was identified as Anna Duvall, 62, of Phoenix. Not long afterward, John Martini, a mob hit man, was convicted of shooting her in the head after she flew to Philadelphia to confront him for defrauding her in a real estate deal. (Martini, who was implicated in three other murders, died in prison in 2009.)

The case that made Bender famous was that of John List, a struggling accountant who shot his mother, wife and three children to death in their Westfield, N.J., home in the fall of 1971, then vanished.

In 1989, Bender was asked by the producers of “America’s Most Wanted” to sculpt an older John List. After studying photographs of the younger man, Bender used the clay to show a face sagging with age.

A woman watching television in Richmond, Va., recognized her churchgoing neighbor, who called himself Robert Clark, wearing just the type of thick-rimmed glasses Bender had put on the bust. The police arrested the man, who proved to be List; he was convicted of the murders in 1990 and died in prison in 2008.

Bender’s bust of the woman found in the woods of eastern Pennsylvania in 2001 was unveiled on April 19 at the fine arts academy in Philadelphia. It has been publicized in the area, so far without results. (A website, www .solvethiscoldcase.com, is dedicated to the case, which is still officially classified as “suspicious.”)

Bender says he has done several dozen sculptures for law-enforcement agencies over the years, and that most led to an identification, an arrest or both. Each bust takes him about a month, and he charges an average of about $1,700 a work.

He does not use a computer, he says emphatically; a computer cannot capture personality.

Bender’s final days are being chronicled in a documentary by Karen Mintz, a filmmaker based in Lambertville, N.J. The title is taken from Bender’s own description of himself: “The Recomposer of the Decomposed.”