Sisters passed a wildfire code for new development. Will Bend be next?

Published 8:00 am Saturday, July 5, 2025

- Sisters Mayor, Jennifer Letz shows an example of defensible space at City Hall in Sisters. 06/11/25 (Dean Guernsey/The Bulletin)

Sisters becomes one of Oregon’s first cities to mandate wildfire buffers

Jennifer Letz was a teenager living in Bend when the 1990 Awbrey Hall Fire tore through 22 homes and thousands of acres on the city’s west side. She watched the smoke column rise from the edge of town as friends evacuated. It left a mark on Letz, who worked as a wildland firefighter and wilderness responder.

In recent years, she’s watched as that type of destruction became more frequent across Oregon and the West.

Now, as mayor of Sisters, Letz is trying to make sure her town isn’t next. Her first line of defense: changing rules for the way neighborhoods are built.

“I don’t want us to lose homes,” Letz said. “Watching all of these other communities go through this … people have died.”

As a state effort to boost resiliency on private property across Oregon died, Sisters pushed a new development code across the finish line meant to protect homes from burning down in wildfires. It requires vegetation-free space around the home and placement of fire hydrants and roads for new construction.

Sisters is now one of the only cities in the state with defensible space enshrined in its development code, potentially setting the stage for others to follow suit. It’s the first piece in a slate of new codes the city hopes will shield it from destructive wildfire as planned growth pushes it closer to the forest.

“Like everywhere else, we’re growing,” Letz said. “It would be insane for us to be building new neighborhoods and new structures that were not built up to the code that science and research and experience has shown can be very effective.”

For new construction, no vegetation other than trees of a certain size will be allowed within 5 feet of a building. Only plants not included on the city’s list of flammable vegetation will be allowed to be planted within 30 feet. Tree branches must be at least 10 feet away from any part of a building. Only non-flammable fencing is allowed. To have plans approved by the city, developers must submit a Fire Prevention and Control Plan, which dictates location of fire hydrants and truck access, along with vegetation management plans.

The code covers all new development within the entirety of Sisters.

“We’re a community of 1.9 square miles. Everybody is at risk here,” said Sisters City Manager Jordan Wheeler.

The Awbrey Hall Fire in 1990 destroyed 22 homes on Bend’s west side. (Bulletin file)

Shift to local control

Wildfire has long been a top concern in Sisters. The city began discussions about changing development code several years ago, around the same time state legislation created the map.

That was in response to Oregon’s devastating 2020 wildfire season, including the Labor Day fires that destroyed about 4,000 homes. The state used a sophisticated computer model to assign a hazard level to every property tax lot in Oregon, tying the riskiest areas to codes for wildfire-resistant buildings and vegetation control.

The city waited for the state’s new defensible space code, but when lawmakers began calling for the hazard map on which it was based to be repealed earlier this year, Sisters moved ahead anyway.

“We’re like, tik-tok, we can’t wait for this anymore,” Letz said. “We’re moving ahead, kind of at our own expense.”

Lawmakers passed a bill that killed the map last month, shifting wildfire codes to local control.

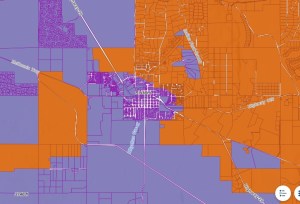

Oregon’s retracted wildfire hazard map shows high hazard areas in orange and moderate hazard areas in purple around Sisters. The state’s defensible space and home hardening codes would have applied only to areas in orange. Sisters’ new defensible space code applies anywhere within the city limits. (Oregon State University)

Chad Hawkins, assistant chief with the Oregon State Fire Marshal’s Office, said the legislation directs the office to follow through with drafting defensible space codes to be available for local adoption.

“That planning stage is a great opportunity to set the framework as those communities start building out and pushing out,” he said.

Though there was debate among the Sisters City Council about how stringent to make the code, any kerfuffle was minor compared to the “chaos” caused in communities by the wildfire map, Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek said in a recent statement. Many rural residents were concerned the map was leading to rising insurance rates. Deschutes County joined others in filing a mass appeal of the wildfire map.

Patti Adair, a Deschutes County Commissioner who lives near Sisters, was a fierce opponent.

But she said the city’s code is a smart idea.

“People have got to get really serious about making sure their house is in the best shape it can be,” she said.

Effects on housing costs

For Letz, the next goal is to pass rules for fire-resistant building materials on new development so homes, not just the space around them, will be protected from fire. Oregon already has a statewide building code for wildfire available for adoption by cities, although few have done so.

Sisters hopes to strike a balance: put enough regulations in place to meet standards that science has shown will prevent homes from burning, but not make them so strict as to hamper the production of affordable housing — a dire need in Sisters.

The state forecasts that Sisters will need to build nearly 1,800 housing units in the next 20 years. About 650 of those will need to be affordable to people earning less than 80% of the area median income. To do that, the city plans to add between 200 to 250 acres through an urban growth boundary expansion that would add about one-fifth more land to the city.

A map shows where Sisters could grow during its urban growth boundary expansion. The highest priority areas are shaded green. Those overlap with areas identified as high wildfire hazard by the state’s map. (City of Sisters)

As with any new regulation, unintended consequences are a concern for some builders, like how the new defensible space codes will interact with codes for tree preservation, said Morgan Greenwood.

And home hardening standards, should they be adopted, could make development — and the cost of housing — more expensive. Oregon’s building code division estimates meeting the state’s wildfire building code costs between $2,500 and $3,000 more for a typical 1,200-square-foot home. That’s a relatively low margin when compared to the cost of a home, but can start to add up with mortgage rates factored in, Greenwood said.

There is another potential hiccup for home builders. Large developers — those capable of delivering a high number of affordable units — buy materials en masse to keep costs down. But with wildfire development standards left up to local jurisdictions, building materials in one place may not be allowed in another.

Will Bend follow suit?

Some studies have shown that using fire-resistant materials to build homes in fact does not add cost, and can even be less expensive. The research is led by Headwaters Economics, a nonprofit research group specializing in community development and land use topics.

“If we’re going to be building homes, let’s require them to be built in a way that keeps them from burning down,” said Doug Green, a former Bend firefighter and land use planner who now runs wildfire programs for the nonprofit.

That’s already happening with new neighborhoods on the west side of Bend, in the potential path of destruction for a fire burning in the Deschutes National Forest — including where the Awbrey Hall fire burned three decades ago. In 2019, Deschutes County created the Westside Transect zone, which limits density to reduce wildfire risk in one of the city’s most vulnerable areas.

The Awbrey Hall fire roared past Skyliners Road shortly before sunset on Aug. 4, 1990. (Bulletin file)

Bend also has a code requiring property owners to manage vegetation on their properties. But developers aren’t required to take wildfire into account.

In recent months, the Bend City Council has been met with a growing concern that large, dense developments at the south edge of town would be sitting ducks during a large fire. The city addressed those concerns on a case-by-case basis, requiring developers to submit wildfire mitigation plans or add emergency evacuation exits.

City officials have also met with several neighborhood groups to address concerns. James Dorofi, board chair of the Old Farm Neighborhood District in southeast Bend, said removing the state’s wildfire map doesn’t change the city’s risk factors. He encouraged more collaboration and education between neighbors to increase resilience.

At the same time, “When it comes to new development, our code needs to be changed,” he said.

The city council has supported a two-pronged process to address wildfire: strengthen codes and ramp up education. But whether that process results in home hardening and defensible space for new development remains to be seen.

“I’m sure staff will be taking a look at what Sisters has now implemented,” Bend Mayor Melanie Kebler said in an email.

City Councilor Mike Riley said people want to see the city move forward assertively with defensible space codes.

“We perceive it as urgent at the city,” he said. “We also want to be thoughtful, ensure that what we’re doing is thought through on the code side, and has as few unintended consequences as possible. There’s always going to be some.”