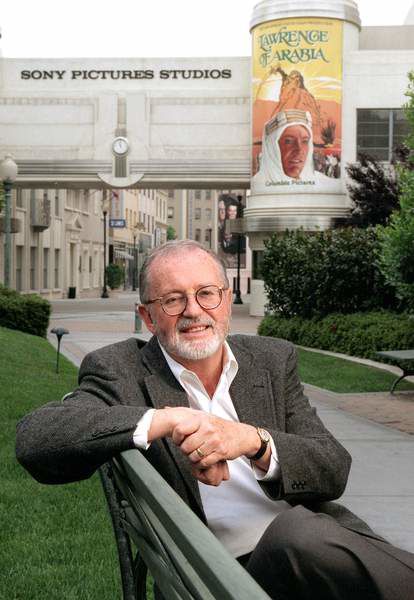

John Calley, studio chief and movie producer, dies

Published 5:00 am Friday, September 16, 2011

- John Calley, a former top executive at Warner Bros., United Artists and Sony Pictures Entertainment and a producer whose credits include “The Remains of the Day” and “The Da Vinci Code” has died. He was 81.

LOS ANGELES — John Calley, a former top executive at Warner Bros., United Artists and Sony Pictures Entertainment and a producer whose credits include “The Remains of the Day” and “The Da Vinci Code,” has died. He was 81.

Calley died Tuesday at his home in Los Angeles after a long illness, according to Steve Elzer, a spokesman for Sony Pictures.

Highly regarded by Hollywood’s creative community, Calley in 2009 was named the recipient of the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He was unable to attend the non-televised dinner ceremony that year because of his health.

The award, given to “a creative producer whose body of work reflects a consistently high quality of motion picture production,” was a prestigious cap to his long career in films.

After becoming an executive vice president at Filmways Inc. in 1960, Calley was associate producer on films such as “The Americanization of Emily,” “The Sandpiper” and “The Cincinnati Kid” and a producer of “The Loved One,” “Castle Keep,” “Catch-22” and other films.

In 1969, he became executive vice president in charge of production at Warner Bros.; he became president in 1975.

“Under Calley, Warners became the class act in town,” Peter Biskind wrote in his 1998 book “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-And-Rock ‘N’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood.”

“Urbane and witty, he gave the impression that he was somehow above it all, slumming in the Hollywood cesspool,” Biskind wrote. “As one wag put it, he was the blue in the toilet bowl.”

At Warner Bros., Calley created what Biskind called “an atmosphere congenial to ‘60s-going-on-’70s filmmakers” and was known for relying heavily on his own taste in picking films.

Among Warner’s Calley-era bill of fare: “Woodstock,” “A Clockwork Orange,” “Mean Streets,” “The Towering Inferno,” “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” “The Exorcist,” “Dog Day Afternoon,” “Deliverance,” “Dirty Harry,” “All the President’s Men,” “Blazing Saddles,” “Superman” and “Chariots of Fire.”

In 1980, the 50-year-old Calley had just signed a new seven-year deal with Warner Bros. reportedly valued at $21 million when he decided to do the unimaginable: quit.

“I wasn’t enjoying it,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1994. “I felt in some wacky way that I had lost myself, that I had no sense of myself and that I was being described by myself by my phone list and the invitations which I never responded to.”

Moving to Fishers Island in Long Island Sound, he became what a New York Times writer described as a “virtual hermit.” He later moved to rural Connecticut.

He spent his mornings playing the commodities market and then spent the rest of the day obsessively reading novels. Summers, he’d sail his boat in the Mediterranean. He rarely watched TV or movies.

“I pretty much stopped living a contemporary life,” he later told Newsweek magazine.

He resurfaced in 1989 as executive producer of the film “Fat Man and Little Boy” and then as a producer on “Postcards from the Edge” (1990) and “The Remains of the Day” (1993), which received an Oscar nomination for best picture.

But for the most part, Calley told Newsweek in 1996, “I was just sleeping more and more. Not a classic depression sleeping, but I enjoyed dreaming more than going to cocktail parties.”

He said he was sleeping 16 to 18 hours a day when talent agent Michael Ovitz called and urged him to come out of retirement to accept an offer to become president of the faltering United Artists in 1993.

At United Artists, Calley quickly discovered it wasn’t the same Hollywood he had left.

“The first month or two were harrowing,” he said in the Newsweek interview. “I didn’t know the grammar, the people. I hadn’t seen a movie in eight or 10 years. I made dopey mistakes, like ‘Tank Girl,’ not getting it, thinking, ‘Is this the world I’ve re-entered? Does everybody have a safety pin through their tongue now?’”

In turning around UA, Calley oversaw hits such as “The Birdcage,” the blockbuster James Bond movie “GoldenEye” and the critically acclaimed “Leaving Las Vegas.”