Frederick Fay, activist for disabled

Published 5:00 am Friday, September 2, 2011

- Frederick Fay, who was paralyzed in a backyard accident as a teenager, spent the final 30 years of his life on his back. He became one of the country's most prominent advocates for the rights of the disabled and was among the first to draw a connection between disabilities and the civil rights movement.

Frederick Fay, who was paralyzed in a backyard accident as a teenager, became one of the country’s most prominent advocates for the rights of the disabled and was among the first to draw a connection between disabilities and the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

He was 66 when he died Aug. 20 at his home in Concord, Mass. He had pulmonary failure, according to his brother.

From the age of 17, when he founded a counseling group for people with spinal cord injuries, Fay was a leading organizer of coalitions to battle discrimination against the disabled.

Through the years, as his own disability left him permanently bedridden, he remained a forceful national voice in demanding that the disabled have full access to buildings, services and the chance for an independent life.

Fay was guided by the same principles that had toppled racial barriers during the nation’s civil rights struggles. He helped disabled Americans gain recognition as a minority group that had long suffered from discrimination.

“He is one of the first people to envision disability rights as a civil rights issue,” filmmaker Eric Neudel said in an interview. “He was thinking that way as early as 1963.”

Neudel recently completed a documentary about the disability rights movement, “Lives Worth Living,” that features Fay’s life story. The documentary is scheduled to be shown on PBS on Oct. 27.

In his early 20s, Fay was part of a group seeking to make public buildings more accessible to the disabled, which helped lead to the federal Architectural Barriers Act of 1968.

While Washington’s Metro system was being built in the early 1970s, Fay coined the phrase “no taxation without transportation” to protest the lack of wheelchair-accessible elevators in the stations. Elevators were installed only after another disabled man won a lawsuit in federal court.

Fay was a primary advocate for two key provisions of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 — sections 503 and 504 — that effectively granted civil rights protection to the disabled by banning discrimination by any groups receiving federal funding.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Fay advised Democratic presidential candidates and rallied support for the Americans with Disabilities Act, which prohibited discrimination in employment, housing and public accommodations throughout the country.

Working with former Reagan administration official Justin Dart Jr., Fay formed a nationwide lobbying effort to support the legislation, which was signed into law in 1990.

All of Fay’s accomplishments in the final 30 years of his life came while he was flat on his back. By 1981, a two-foot-long cyst on his spinal column, called a syringomyelia, made it difficult for him to swallow and breathe unless he was in a supine position.

“I went from a push chair to a power chair to a motorized stretcher in a year,” he told the Boston Globe in 1997.

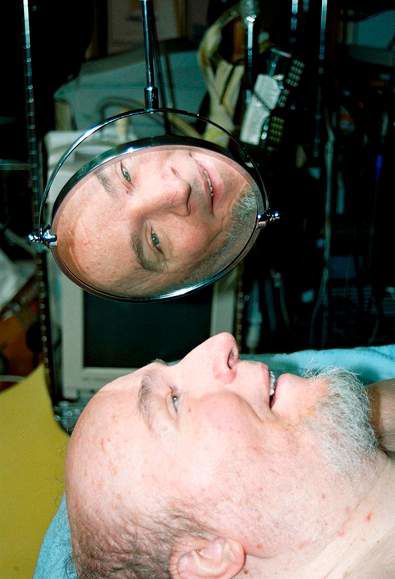

As a onetime computer programmer for IBM, Fay was a proponent of technology to assist people with disabilities. He designed the motorized bed and a system of mirrors that enabled him to navigate around his house. He was using electronic mail in the early 1980s.

He could open doors and windows, operate a television, and turn lights on and off from the dozens of buttons on his bedside console.

Fay managed his vast communication network through a telephone mounted on his bed and a computer monitor that hung from the ceiling. He balanced the computer keyboard on his chest and viewed it in a mirror suspended above his bed — reading the letters upside down and backward.

“The key role Fred has played over the years was as a visionary, leader and organizer of people toward a common cause,” said Elmer Bartels, who has been active in disability rights since the 1960s and spent 30 years as commissioner of rehabilitation in Massachusetts. “He was doing all this communication work from a motorized wheelchair bed.”

Frederick Allan Fay was born in Washington on Sept. 12, 1944, and grew up in Bethesda, Md. His father was an engineer, and his mother was from a well-to-do Washington family.

He was a member of the high school rifle team and excelled in athletics.

In 1961, at age 16, he slipped from a trapeze in his family’s back yard, fell 10 feet and landed on his forehead. He broke two vertebrae in his neck.

He was treated at the National Institutes of Health and later spent several months at a rehabilitation facility in Warm Springs, Ga., where President Franklin D. Roosevelt had received therapy.

Back in Washington in 1962, the teenager and his mother, Janet, formed a counseling group, Opening Doors, for people with spinal cord injuries.

He finished high school with the help of tutors and then went to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, one of the few colleges at the time with accommodations for students with wheelchairs. After graduating in 1967, he worked for IBM in Gaithersburg, Md., for three years, testing elements that later became part of the Internet.