Prefab, but far from ordinary

Published 5:00 am Tuesday, September 13, 2011

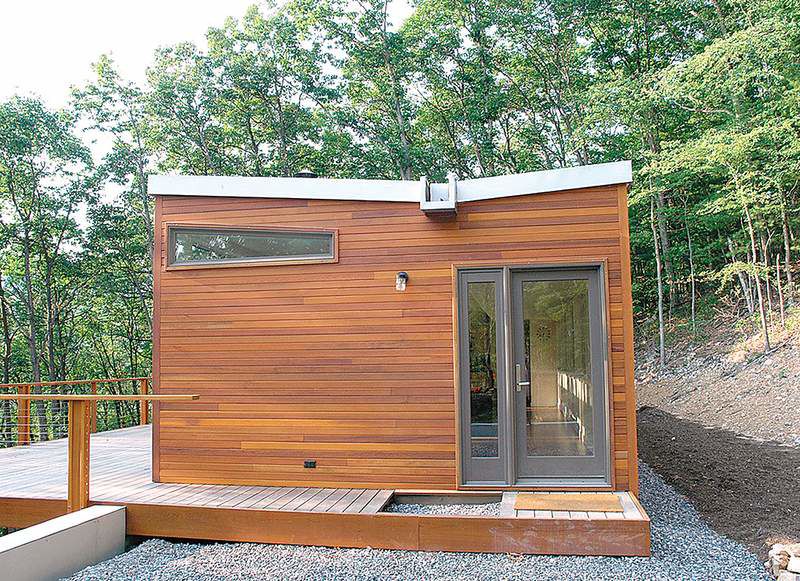

- The living room, dining area and kitchen of Chris Brown and Sarah Johnson’s prefabricated home in West Virginia. A wide deck runs the length of the open-plan great room. When finished, prefabs can look like regular houses.

We hadn’t been inside the West Virginia cabin for more than 15 minutes when my friend Jane pulled out a 25-foot tape measure. OK, the place was about 16 feet wide. Length? Well, two 25-foot lengths plus the hallway and then the bedroom for a total of 64 feet. A wide deck ran the length of the open-plan living-dining-kitchen, offering views of green, green, green. Inside and out, the place was modern, lined with white walls and lots of glass and dotted with iconic bits of midcentury-modern furniture.

Jane was excited because the cabin was prefab, and she has a nice lot looking onto the Chesapeake Bay. Right now it’s topped by her childhood summer cabin. But wouldn’t it be nice, she wondered, to replace it, or augment it, with a modern prefab structure?

Trending

By now it’s fair to say most people do not confuse prefab houses with mobile homes. Prefab is simply a different system for building a regular house, of almost any style, producing it in either modules or panels in a factory. With modular houses, there’s a lot of extra engineering involved: After all, at the factory and at the homesite, pieces of the structure have to be picked up by a crane and set in place, first on the delivery rig and then on a concrete foundation — and in between they bounce around for miles on a truck. With panelized construction, sections of walls, complete with innards such as electrical wires, are stacked on trucks, then linked together on site. When finished, prefabs look like regular houses.

People do, however, continue to equate prefab with cheap, or at least considerably cheaper than traditional “stick-built” construction. But there is a wide spectrum of prefab houses and the companies that make them.

At one end, you have factories that spit out econoboxes that, despite their superior engineering, can resemble shipping containers. They include the one-bedroom, one-bath “i-house” by Tennessee-based Clayton Homes, which can be had for a base price of $75,812. Adding upgraded flooring and appliances takes it to about $85,000 including delivery, or about $117 a square foot. ECO-Cottages by Nationwide Homes of Martinsville, Va., offers a 513-square-foot, one-bedroom, one-bath “Osprey” cottage starting at $59,500, or $116 a square foot. (Prefab prices do not include the cost of the land, foundation or site-prep work.)

High prices here, too

At the other end of the cost spectrum are such firms as California-based LivingHomes, which offers high-style contemporary designs at square-foot costs that range from $220 to $250, and much more for custom designs. That doesn’t even include design fees. What you’re getting, the company says, is a soaring architect-designed house — steel frame, lots of glass — for 20 to 40 percent less than a similar house would cost if it were site-built.

Compare these numbers with a 2,200-square-foot house currently offered by Ryan Homes in Clinton, Md. — $121 a square foot including the land it sits on — and the decision to go prefab is not as clear-cut as it may seem.

Trending

The cabin we were visiting belongs to Chris Brown and his wife, Sarah Johnson. During construction of their cabin, called Lost River Modern, Brown kept a blog, including his estimates of what he thought things were going to cost and then the real dollar amount.

Jane and I looked over the blog. When we saw the staggering $356,000 total to build the very nice two-story three-bedroom, two-bathroom 2,048-square-foot house in far-out West Virginia, Jane began revising her expansion fantasy.

The cabin is part of a mini-slice of the prefab world: stylish, higher-end houses designed by architects interested in homes that are built in a way that’s more labor- and energy-efficient and less wasteful than site-built houses.

Brown and Johnson were thinking about a getaway house that they could rent out when they saw the winner of the 2003 Dwell Magazine prefab-house competition. Sixteen architects and designers were invited to create an innovative prefabricated house for $200,000 — one more effort to stoke the fire under prefab, which is always threatening to peter out in the face of market realities.

Bars over cubes

The winner was Resolution: 4 Architecture of New York, and Brown approached principal Joe Tanney in 2006. Where some prefab designers think in terms of cubes and at least one thinks in terms of triangles, Res4 thinks about “bars,” long or short sections that can be stacked or angled or cantilevered to achieve interesting effects.

Res4 had a new relationship with a builder, Simplex Industries of Scranton, Pa. Designing a prefab house means nothing without access to a factory that can construct it. Architects don’t own factories, as a rule, and mass-production factories are not necessarily disposed to interrupting their assembly line for a small project.

With contemporary design there’s an additional challenge: The architect or the owner has to find a modular construction company that is attentive to finishes. “With modern,” Brown says, “you can’t hide everything with molding like in traditional-style modular houses.”

David Boniello, vice president for marketing and development at Simplex, says “a lot of thought goes into a room” by Res4 and other design firms. That leads to challenges for a manufacturer. “These guys are architects. They want 523⁄8,” not just 53 inches. Also, contemporary architects design a lot of large floor-to-ceiling openings to make place for glass, and those pieces can be tricky to transport, Boniello said.

An advantage of prefab is supposed to be the time savings, and it’s true that the factory can start on the component parts of the house while a crew is still pouring the foundation — impossible, of course, with site-built construction. But tweaking machinery and refining designs still takes time. Brown estimates the house was “in the factory” for a year.

Another year was spent after delivery, finishing details such as some complicated flashing for the Charles Goodman-style “butterfly” roof and the interior, with Brown and his brother-in-law providing a lot of the labor. (They also applied the exterior cedar siding and built the deck, then tackled the interior of the lower level, even building the staircase and tiling the bathroom.)

Brown, a graduate student in English literature, said the “real advantage” was that he and Johnson, a nurse, “didn’t have to manage a building site” that was almost three hours from their home in suburban Washington.

Without the land cost, excavation or the $12,000 for the road up the side of their hill, Brown and Johnson calculate their square-foot cost as $150 to $160, “the low end of prefab,” Brown said. At least of “architect prefab.”

Res4 and Simplex’s attention to detail shows up in an interesting way in the Lost River Modern cabin. The 16-by-64-foot modular level made by Simplex rests atop a walk-out basement foundation, made on site by a local contractor and still being finished by Brown and his brother-in-law. The difference between the two levels is in the details, but they add up. Upstairs the light switches all have dimmers, the floor is bamboo, pocket doors are frosted glass in a light-wood frame, built-in kitchen and bedroom cabinetry is precise and the ceramic-tile bathroom, delivered on a truck, is in perfect condition. Aside from the Res4-specified windows and doors, the downstairs might be called “builder grade”: light switches are simple toggles, the floor is polished concrete, the bathroom has caulking and grout problems and some gapping where the walls meet the floor (probably settling, Brown guesses). Upstairs, the closets have nicely engineered, close-fitting doors.

Rent for the Lost River Modern cabin starts at $250 a night. Method Homes’s 1,811-square-foot Method Cabin 1 (base model $271,650 and higher) at Mt. Baker in Washington state, rents for $250 to $300 a night. The owners of a weeHouse by Alchemy Architects of Minneapolis, located on the Oregon Coast, rents from $225 to $275 a night (oceansideprefab.com).

As for Jane, she’s still thinking about it.

Info and sources

There are quite a few companies that make general prefab homes. But there are also niches claimed by various manufacturers.

Tiny Texas Houses (www.tinytexashouses.com) specializes in small cabins made with salvaged wood and other materials; from $35,000 to about $75,000.

BrightBuilt Barn (www.brightbuiltbarn.com) of Maine makes simple houses with SIPs (Structural Insulated Panels) and solar panels and no furnace, on the grounds that the occupants’ own body heat will keep them cozy inside the superinsulated interior; about $197,000 including transport but not appliances.

The Homb, (www.welcomehomb.com) designed by Skylab Architecture (www.skylabdesign.com) and made by Method Homes (www.methodhomes.net) of Seattle, is made with triangular modules, leading to interesting angles and outcroppings of glass; they start at $160 per square foot. Method Homes’ Cabin series houses start at around $185,000.