Oregon obesity rates worsen

Published 5:00 am Friday, July 8, 2011

- Oregon obesity rates worsen

Obesity rates in Oregon continue to worsen, with one in four adults now obese and three out of five overweight. But the state obesity rate for children age 10 to 17 is the best in the nation.

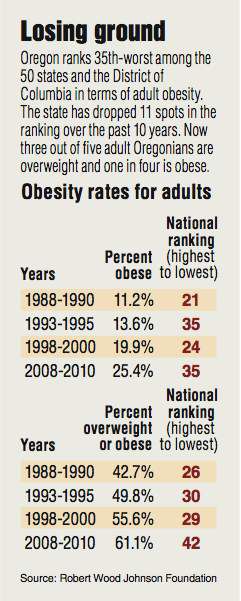

According to a new report issued Thursday by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Trust for America’s Health, Oregon had the 35th-worst adult obesity rate in the country, at 25.4 percent, improving its ranking from 24th a decade earlier, when 19.9 percent were obese.

But Oregon moved down 11 slots only because other states got fatter faster. Oregon’s obesity rate has risen nearly 87 percent over the past 15 years, but that still lagged behind the growth in obesity rates for at least 17 states.

“The national rankings are one thing, but we’re really concerned about where we’re going in Oregon,” said Dr. Bruce Gutelius, deputy state epidemiologist. “We do know that Oregon is still facing a crisis with obesity. We have seen a continuing upward trend in both obesity and overweight status in Oregon.”

People with a body mass index of 25 of higher are considered overweight, and those with a BMI over 30 are considered obese. A 5-foot-4-inch tall person would be obese carrying 30 extra pounds.

Gutelius said rates are growing due a combination of factors that aren’t unique to Oregon.

“When we talk about obesity, it’s calories in and calories out, and we need to address them both to make a difference,” he said.

Obesity rates have generally been lower in Western and Northeastern states, and higher in the Southeast. But no states have made significant progress in slowing the growth of obesity rates over the past decade. Two-thirds of states, including Oregon, now have obesity rates above 25 percent.

“Today, the state with the lowest adult obesity rate would have had the highest rate in 1995,” said Jeff Levi, executive director of the trust. “There was a clear tipping point in our national weight gain over the last 20 years and we can’t afford to ignore the impact obesity has on our health and corresponding health care spending.”

The consequences of obesity include a higher risk for diabetes and high blood pressure, and Oregon’s rates for both conditions compared to other states fell in line with its obesity ranking. But Oregon did score well in terms of physical activity, finishing second only to Minnesota in the number of adults who got regular exercise.

Obesity rates were also closely correlated to socioeconomic factors. Those with less education and lower income were more likely to be overweight or obese. And minority groups tended to have the highest overall obesity rates. Oregon’s above-average status may be linked in part to its racial make-up, with minorities represent only 10 percent of the population.

Despite the rising obesity rates for adults, Oregon has attracted the attention of obesity experts trying to decipher why the state child obesity rate — at 9.6 percent — is the lowest in the nation.

“Some of the theories I’ve heard is that we have a really high breast feeding rate, and breast feeding has been shown to be protective against obesity,” said Kate Wells, project director for Kids@Heart, a Central Oregon childhood obesity prevention initiative. “But other than that, there’s no way to know which driver is working in our favor.”

The Kids@Heart initiative has launched several projects seeking to keep childhood obesity rates from rising any further, including recruiting pediatricians at Mosaic Medical and Central Oregon Pediatric Associates to write prescriptions for healthy, active living for children at risk for obesity and its consequences.

For higher-risk cases, the program calls in play coaches that can work with families to overcome barriers to more active lifestyles, such as helping them with the cost of attending recreational programs.

The group is also using the successful 5210 framework for healthy living that was first tested in Portland, Maine. The approach urges kids to get five servings of fruits and vegetables per day, no more than two hours of screen time, at least an hour of physical activity and zero sugar-sweetened beverages. Local advocates are using 75210, adding a healthy breakfast seven days a week to the recommendations.

“American society couldn’t do a worse job at the moment of keeping children fit and healthy — too much TV, too many food ads, not enough exercise, and not enough sleep,” said Dr. Victor Strasburger, a member of the American Academy of Pediatric panel that last month called for less screen time for children. “We’ve created a perfect storm for childhood obesity — media, advertising, and inactivity.”

Oregon officials have implemented a number of statewide initiatives targeting obesity for both adults and children. Last year, the state required restaurants with 15 or more outlets to provide information on the calories, saturated fat, trans fat, carbohydrates and sodium in their menu items upon request. The Oregon Public Health Division also awarded grants to a dozen counties, including Deschutes County, to form community partnerships addressing the chronic diseases most closely linked to physical inactivity, poor nutrition and tobacco use. The latest report also cited Oregon’s school nutrition policies and complete street laws — which accommodate by cyclists, pedestrians and transit users — as factors that put Oregon’s obesity rates below the national average.

“In general, what needs to be addressed are the problems that people have in terms of getting access to healthy food options and being able to have enough opportunities to exercise,” Gutelius said. “And there are multiple different policy options to address those.”