‘Granny pods’ could change elder care

Published 4:00 am Monday, November 26, 2012

- ‘Granny pods’ could change elder care

Viola Baez wouldn’t budge.

Her daughter’s family had just invested about $125,000 in a new kind of home for her, a high-tech cottage that might revolutionize the way Americans care for their aging relatives. But Viola wouldn’t even step inside.

She told her family she would rather continue living in the family’s dining room than move into the shed-size dwelling that had been lowered by crane into the backyard of their Fairfax County, Va., home.

“You’re throwing me out! You’re sending me out to a doghouse! Why not put me in a manicomio?” Viola, 88, told them, using the Spanish word for madhouse.

Then the air conditioner blew. As temperatures and tempers soared in the main house, Viola’s family coaxed her into the cottage to cool off. Viola stayed the night, then another, and another, until summer had turned to fall.

As the first private inhabitant of a MedCottage, Viola is a reluctant pioneer in the search for alternatives to nursing homes for aging Americans. Her relatives agonized over the best way to care for Viola only after her ability to care for herself became questionable.

Their decision exposed intergenerational friction that worsened after the new dwelling arrived.

The MedCottage, designed by a Blacksburg, Va., company with help from Virginia Tech, is essentially a portable hospital room. Virginia state law, which recognized the dwellings a few years ago, classifies them as “temporary family health-care structures.” But many simply know them as “granny pods,” and they have arrived on the market as the nation prepares for a wave of graying baby boomers to retire.

Over the past decade, the population of Americans who are 65 or older has grown faster than the total population, the Census Bureau says. In less than 20 years, the number of Americans who are 65 or older will top 72 million, or more than twice the population of older Americans in 2000, and many will need to find living arrangements that balance their need for independence and special care.

Viola’s family understood this. Her daughter, Socorrito Baez-Page, 56, who goes by Soc, and her son-in-law, David Page, 59 — both of whom are doctors — began planning her care well before Viola’s husband died of cancer last February. They explored many options and had firsthand experience with several. Soc and David had taken care of or arranged various types of care, including assisted living and hospice, for other parents.

Several firms have entered the market for auxiliary dwelling units, or ADUs, as they’re known in the building industry. These include FabCab, a Seattle-based company that makes ADUs and full-size homes. Practical Assisted Living Solutions, or PALS, a firm based in Meriden, Conn., makes freestanding modules; and the Home Store, which is headquartered in Whately, Mass., sells modular “in-law” additions called “Elderly Cottage Housing Opportunity” additions.

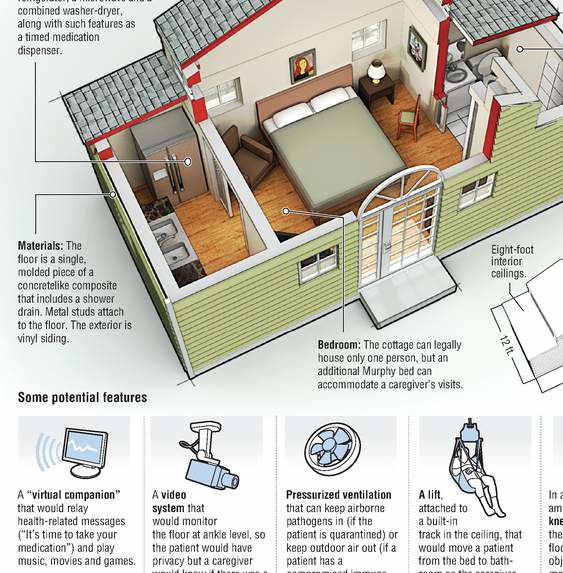

The MedCottage in Fairfax is about 12 by 24 feet, the size of a typical master bedroom. With its beige aluminum siding — and cosmetic touches such as green shutters — the cottage looks a little like an elaborate dollhouse.

The idea for the MedCottage came from the Rev. Kenneth Dupin, a minister in southwest Virginia who wondered why Americans didn’t take better care of their elders. He created N2Care, a company that designed the MedCottage with help from the Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center. They stuffed its steel shell with the latest in biometric and communications technology, and crafted its features using universal design principles to accommodate people of all ages and people with disabilities. The company’s sales pitch includes dropping an egg onto its specially designed floor from a height of 7 feet to show that the egg won’t break.

In addition to surveillance cameras, the dwelling has an Internet portal by which family members, doctors or other caregivers can monitor an occupant’s vital signs, receive medical alerts or change the dwelling’s temperature and security settings. The MedCottage retails for about $85,000, but with delivery and installation, Viola’s family has spent closer to $125,000.

“Most people look at that and get sticker shock,” Cummins said.

But Cummins also said that the company offers financing and repurchase programs that make the MedCottage a bargain compared with assisted-living facilities that charge $40,000 or more a year.