Accordion resurgence in Redmond

Published 4:00 am Saturday, February 19, 2011

- Accordion resurgence in Redmond

Pulling the bellows apart with a flourish, Terry Ranstad launched into a haunting melody, right hand pausing on the accordion keyboard in firm chords.

It took a second to identify the visceral reaction to the music: the theme from “The Godfather” movies. The song, Ranstad said, is actually one of love in Italian.

“You have to squeeze it, make love to it a bit,” Ranstad said, explaining how to inject passion into the music with the instrument. The accordion doesn’t look that large against Ranstad, a former college football player, although it’s a good 25 pounds.

For decades, the Bend resident let his accordion, a gift from his father, collect dust in a closet. Now he’s 61, and the instrument has become his passion.

“It’s fun music ; it’s just fun,” he said. “You start to play and the smiles come out.”

Ranstad is not alone. While in recent decades accordion music in American culture has been the stuff of nerdom — think Urkel in “Family Matters” and “Weird Al” Yankovic — it’s now popping up in some prominent places.

In 2009, an accordion soloist played Carnegie Hall for the first time in roughly 30 years. Symphonies are enlisting accordionists as guest artists. And rock bands from The Decemberists to this past week’s Album of the Year Grammy winner, Arcade Fire, are incorporating the accordion into their music.

The Accordion Club of Central Oregon sprang up within the last two years, gathering once a month in Redmond to learn new music, exchange tips and jam. Its list quickly grew to 30 players.

While there’s nothing scientific to measure it, enthusiasts say the accordion is on its way back.

“The accordion is alive and well in Central Oregon,” declared Redmond resident Karl Kment, 83, who played as a youth and about 15 years ago took it up again.

Rise and fall

of the accordion

There was a time when the accordion was one of the most widely played instruments in the country.

The accordion has long been popular in other cultures. The first version, Kment said, originated in China. By the mid-1800s, musicians played different versions of the accordion throughout Europe, incorporating it into folk music from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean.

Its popularity came to the U.S. with immigrants, who played traditional dance music like tarantellas from Italy and schottisches from Germany. Musicians also mixed the accordion into North American folk music, particularly in Cajun and Mexican communities.

Then came the 1950s, which Kment termed “the golden age of the accordion.”

It was a common instrument for children and teenagers in the ’50s to learn. Ranstad recalled that, growing up then, every small town — including his, Grants Pass — had an accordion studio .

By then, the most popular type of accordion played in North America was the piano accordion, with its piano-like keyboard on the right side and series of buttons on the left.

Although it has a keyboard like the piano, the accordion is actually more like a pipe organ, said Kment, who once owned five music stores across Oregon.

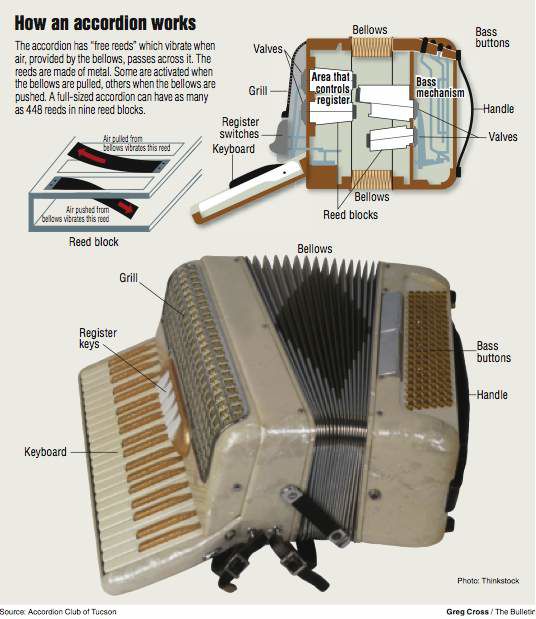

The accordion is a wind instrument, but unlike a clarinet, for instance, the reeds are metal instead of wood. The musician moves air over the reeds by manipulating the accordion’s bellows, controlling volume in the process. Pressing a key on the keyboard or a button on the left side of the accordion frees reeds to vibrate in the moving air and make sound.

The keyboard produces the melody and the buttons the bass. And there are registers, like on an organ, that allow the musician to switch the reeds so the accordion makes different sounds, from oboe to clarinet to piccolo. Because of this versatility, Kment said, the accordion is the only instrument with which musicians can play orchestral music “fairly authentically” alone.

And due to all the reeds — in a full-size accordion there can be almost 450 of them — piano accordions are fairly heavy, often weighing between 25 and 30 pounds. There are now also models available in which the reeds are replaced by electronics, making the instrument lighter.

The quality of accordions vary, and high-end accordions involve artistry, said Lillian Jones, a La Pine resident who plays with the Accordion Club of Central Oregon. The most expensive ones can go for between $10,000 to $30,000.

The accordion’s popularity continued into the 1960s but started to wane, Kment said, when The Beatles came to America. Suddenly, all the young people wanted to learn guitar.

“I should have been in the van business,” Kment chuckled, recalling how he would sell huge amplifiers from his music shops to accompany the guitars, and soon young musicians were driving vans to cart the equipment around.

Rediscovering

the instrument

Last Saturday , eight accordion players gathered in a semicircle at the Cougar Springs Assisted Living Center in Redmond. First they practiced a piece together under Kment’s direction. Then they shared music they’ve been practicing on their own. And lastly, they launched into what they called their jam session, playing crowd pleasers like “Beer Barrel Polka” and “My Blue Heaven.”

Their stories of how they got into playing the accordion share similarities.

They learned to play as children, sometimes at the behest of their parents. As they grew into adulthood, families and careers took precedence, and their musical instruments were shoved into storage.

Now, decades later, they’re digging them out and dusting them off.

Ranstad said his father, who valued music, worked as a real estate agent. One day he came home with an accordion so his son could play the instrument. He had accepted it in lieu of a down payment on a house.

“It’s part of our family heritage now,” Ranstad said. “My parents sacrificed for me to play.”

Kment said he stopped playing accordion when he owned music stores. Instead, he learned the organ so he could demonstrate it to customers.

Yet at the age of 12, Kment “strolled” with his accordion in restaurants and clubs, which paid him for his music. He also remembers traveling with an outfit that went town to town showing movies, as many little towns then didn’t have theaters. When something would go wrong with the projector, which Kment said was often, he would play accordion for the crowds to keep them happy.

Jones, 71, started again when she moved to Central Oregon more than a decade ago. At 7, she said she begged her mother for lessons. Then, at age 15, she auditioned to take lessons with Myron Floren, of “The Lawrence Welk Show.” He accepted her. She later gave lessons herself and was part of a band.

Then, Jones said, she raised a family of four children. Her interest in music took a back seat until recently.

Some, like Kment, play for their own enjoyment, although he accepts an occasional gig. He estimates he can play between 3,000 and 3,500 songs from memory.

Others play more publicly. Ranstad intends to play in the next Central Oregon’s Got Talent competition. And he and Jones both said they have placed in their age groups at the annual Leavenworth International Accordion Celebration in Leavenworth, Wash.

Ranstad said he expects more people will resume playing the accordion and pass it down to their grandchildren.

“When I play for high school kids or little kids, they’re fascinated,” he said. “It’s a romantic instrument.”

More info:

The Accordion Club of Central Oregon meets at 1:30 p.m. on the second Saturday of every month at Cougar Springs Assisted Living Center,

1942 S.W. Canyon Drive, in Redmond. Contact: kgkment@aol.com.