Carlos Andres Perez, former president of Venezuela, dies

Published 4:00 am Monday, December 27, 2010

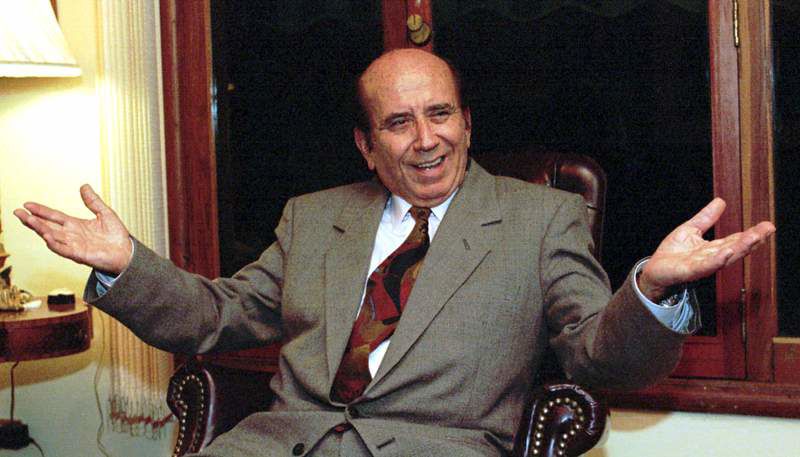

- Former Venezuela President Carlos Andres Perez gestures during an interview at his home in Caracas, Venezuela, in September 1996. Perez died Saturday in Miami at 88.

CARACAS, Venezuela — Carlos Andres Perez, the former president who tried to make Venezuela a leader of the developing world during a 1970s oil boom only to have his legacy upended in a tumultuous 1989 return to the presidency marked by civil unrest, coup attempts, impeachment and exile, died Saturday in Miami. He was 88.

The cause was a heart attack, his daughter, Maria Francia Perez, told the news network Globovision.

Trending

Perez burst onto the Latin American political scene in the mid-1970s when a quadrupling of oil prices suddenly enriched Venezuela’s government, opening the way for state-led development efforts and an era of glitzy consumption known here as “Venezuela Saudita,” or Saudi Venezuela.

A gifted orator known for his bushy sideburns and flashy suits, Perez nationalized Venezuela’s oil industry and the holdings of U.S. iron-ore companies. At the same time, he secured a vocal role for Venezuela in hemispheric affairs, portending, in some ways, President Hugo Chavez’s more assertive foreign policy.

In his first term, Perez re-established ties with Cuba and donated a ship to Bolivia, in support of that landlocked nation’s aspiration to regain sea access. He opposed the right-wing Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua and encouraged Omar Torrijos, Panama’s leftist military leader, in his effort to gain sovereignty over the Panama Canal.

Cultivating an independent streak that sometimes put him at odds with Washington, he tried to strengthen the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, of which Venezuela was a founding member. With that goal in mind, he bought a full-page ad in The New York Times in 1974 to publish a letter to President Gerald R. Ford.

“The establishment of OPEC was a direct consequence of the developed countries’ use of a policy of outrageously low prices for our raw materials as a weapon of economic oppression,” Perez wrote.

Perez was born Oct. 22, 1922, the 11th of 12 children, to parents who were coffee planters in Rubio, a town near the western border with Colombia. He studied law in Caracas and, in 1948, married his first cousin, Blanca Rodriguez, with whom he had six children.

Trending

He was imprisoned that year for his opposition to a military coup and went into exile in 1949, roaming between Colombia, Cuba and Costa Rica, where he worked as editor of the newspaper La Republica.

With the establishment of democratic rule here in 1958, he became a rising star in the government of President Romulo Betancourt. As interior minister, he oversaw a counterinsurgency against Cuban-backed guerrillas. Later, at the helm of the Democratic Action Party, he mounted his successful 1973 bid for the presidency.

That five-year term was marked by the rise of new fortunes in the private sector. Business deals were said to be discussed in the mansion belonging to his mistress, Cecilia Matos, who wore a gold replica of an oil tower on a chain around her neck; she said “Papi,” as she called the president, gave her the necklace, according to Fernando Coronil, a Venezuelan anthropologist at the graduate center of the City University of New York.

After his departure from office in 1979 and the bust in the 1980s that shook Venezuela’s economy, Perez returned to power in 1989 following a campaign that demonized multilateral institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Yet soon after taking office, Perez put in place an austerity program that included a $4.5 billion loan from the IMF. He announced spending cuts and raised gasoline prices, triggering the chaotic episode in February 1989 called the “Caracazo”: rioting and suppression by the security forces that took hundreds of lives.

Perez faced two coup attempts in 1992, the first of which was led by Chavez, thrusting the then-unknown lieutenant colonel into the national spotlight.

Despite the turbulence of his second term, Perez still sought an active role for Venezuela in regional politics. He forged warm ties with Jaime Paz Zamora, the former Bolivian president, and sent a plane for Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the former Haitian president, when he was ousted in 1991.

Still, resentment here festered against Perez, culminating in his impeachment and removal from office in 1993 on corruption charges involving a secretive fund used in part to pay for the bodyguards of Violeta Chamorro, the former Nicaraguan president.

“When the country’s future seemed promising, his power seemed immense; when conditions deteriorated, he was abandoned even by his own supporters,” said Coronil, the anthropologist. “His trajectory illustrated the transient nature of power.”