Westwood No. 1, but for how long?

Published 5:00 am Wednesday, November 3, 2010

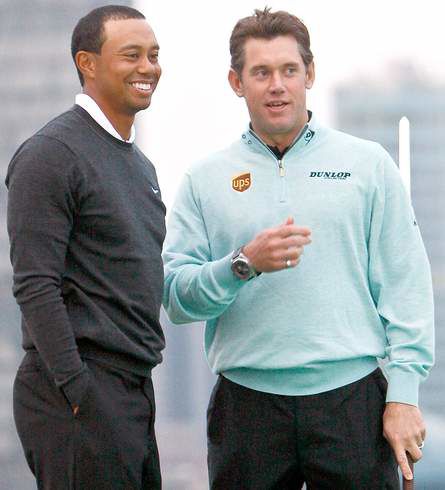

- Tiger Woods, left, chats with Lee Westwood as they arrive for a photography session on top of a hotel in Shanghai, China Tuesday.

SHANGHAI — The first encounter between Lee Westwood and Tiger Woods since they switched spots in the world ranking was not exactly the momentous occasion some thought it might be.

A pair of photographers crouched into position on the far end of the range at Sheshan International, where Westwood was quietly hitting wedges and Woods was quickly approaching from the putting green.

Trending

“Westy … Billy,” Woods called out to the new No. 1 and his caddie, Billy Foster.

He never stopped to chat.

“Tiger,” Westwood responded, turning his head briefly before settling over his next shot.

They have been friends for as long as they have been on their respective tours, and the exchange was similar to countless others. The only difference was the pecking order in the world ranking, and even that comes with a dose of perspective.

Being No. 1 in the world is a big deal to Westwood, as it should be. On the home page of his website is a photo of him standing before a map of the world, cradling a globe and holding up the No. 1 sign.

“Whenever you can sit down and say, ‘I’m the best in the world right now,’ it’s a dream that everybody holds,” he said.

Trending

Losing the No. 1 ranking is not a big deal to Woods, nor should it be.

He had been at the top for a record 281 consecutive weeks. A year ago, it looked as if he might be there the rest of his career until his personal life and golf game imploded. The only surprise for Woods is that it took this long for someone to replace him.

“To be No. 1 in the world, you have to win regularly,” Woods said. “And I haven’t done that lately.”

All of that can change this week at the HSBC Champions, and not just between them.

The top of golf is so crowded at the moment that four players — Westwood, Woods, PGA champion Martin Kaymer and Masters champion Phil Mickelson — could get to No. 1 this week without even winning. If Steve Stricker and Jim Furyk had come over to China for this World Golf Championship, they also would have had a shot at No. 1.

It’s possible that the highest finisher among Westwood, Woods and Kaymer will go to No. 1 in the world, provided they’re in the top 20.

Golf is no longer about birdies and bogeys these days. It requires a calculator.

To kick off the festivities this week, the latest version of the “Big Four” gathered on Shanghai’s riverfront and touched swords in a photo opportunity to depict what organizers hope will be an epic battle for No. 1.

But that’s just this week.

All four players realize that this competition will continue after Shanghai and stretch into Singapore, Australia, Dubai, South Africa and California — at tournaments they play the rest of the year.

This business of No. 1 isn’t likely to be settled anytime soon.

“It could — to really, definitively know — take a year,” Hunter Mahan said. “We’re all waiting for Tiger to get back to where he has been. This year, he had some stuff to go through. But when he gets that straightened out, we expect him to be as good as ever.”

That remains to be seen.

This is the 10th time in his career that Woods was replaced atop the world ranking. Historically, he doesn’t lose the No. 1 spot as much as he loans it out. But he has never been as unpredictable as he is now.

And while interest in America tends to peak when Woods is demolishing his competition, it becomes fascinating worldwide with four players whose ranking average is separated by less than a half-point.

“This could be very exciting for the game,” Westwood said.

The top spot changed hands 10 times between Seve Ballesteros and Greg Norman over a three-year period in the late 1980s. This is more reminiscent of 1997, when four players — Woods, Norman, Ernie Els and Colin Montgomerie — were in the hunt for No. 1 around the U.S. Open at Congressional.

The first time Woods was No. 1, it lasted a week before he was replaced by Els, who was supplanted by Norman a week later, and then it went back to Woods. It rotated among those three during the next year before the music stopped and Woods took over.

Woods, though, has been No. 1 for so long — all but 32 weeks since the 1999 PGA Championship — that to suddenly see so many other players in the mix has given many more belief that it can be done.

Consider the case of Westwood. Woods had a lead that was nearly triple in the world ranking a year ago, yet Westwood still managed to overtake him despite winning only twice, neither of them a major. He was consistently better than anyone else, with two runner-up finishes in the majors, a tie for fourth in The Players Championship, nine top 10s and only one missed cut.

“It gives everyone hope,” Mahan said. “It’s been a long time since someone other than Tiger Woods has been ranked No. 1. Obviously, we all know it’s possible in a sense. It just takes good play, and some good luck.”

The good luck in this case was Woods’ misfortunes, all of it his own doing.

The question now is how quickly he can put his game back together, and whether he can get back to the level where he was winning nearly half the tournaments he entered.

Even at No. 2 — and he could slip to No. 4 by the end of the week — Woods still seems to be the one dictating the action.

Westwood was asked Sunday evening if he still considered Woods his main rival, or if he thought the challenge more likely would come from the growing pack of youngsters, either someone like Kaymer, Dustin Johnson or Rory McIlroy.

“I wouldn’t write Tiger off as quickly as that,” Westwood said. “I certainly wouldn’t. He’s proved that time and time again when he’s gone away and comes back.”

Stadium booths, sidelines and studios are packed with former players, managers and coaches, some blathering with more intelligence than others. But where are the former referees and umpires who can make the sort of quick, informed judgments that can give broadcasts something fresh?

A rare one to have made the switch is Mike Pereira, a former NFL sideline judge and vice president for officiating who is Fox’s rules analyst — and is proving the wisdom of his hiring.

Pereira watches the afternoon games at Fox’s production center in Los Angeles and goes on the air several times each Sunday to interpret rules that are being questioned and to predict how referees will rule on coaches’ challenges. With the NFL, his job included watching games from a league command center and communicating with networks. But his analysis was for internal consumption.

“With the league, if I had to react to a play, I would do it on Monday,” he said during a call from his home in Sacramento, Calif. “I didn’t have to make a snap decision. Now I do.”

On Sunday he was on Fox twice during the Green Bay-Jets game, most tellingly when Jets quarterback Mark Sanchez’s pass to Jerricho Cotchery was intercepted by Tramon Williams.

Cotchery and Williams went to the ground with joint possession but Williams tore the ball away.

Fox’s announcers, Kenny Albert and Daryl Johnston, were certain the ball belonged to Cotchery. “Tie goes to the runner in baseball,” Albert said. “Tie goes to the receiver in football.”

Johnston said, “It should be a completion for the Jets.”

But they were wrong, as Pereira quickly pointed out, clearly explaining the rule and seeing little possibility that the referee Jeff Triplette could uphold Jets coach Rex Ryan’s challenge. His explanation was so smooth that it did not sound as if he was saying the Fox voices blew the call.

“You don’t see simultaneous possession much, but we’ve dealt with it in the past,” he said in the interview. “And what’s interesting is that it’s no different than a fumble recovery. Who recovers is not reviewable. There was really nowhere for the Jets to go. They were never going to get the ball by virtue that the receiver had control of the ball and was down by contact.”

If he still worked at the league, he said, he would have asked Triplette why he granted the challenge and what Ryan said to him. “I would want to use it as a training play for referees,” he said.

So far, Pereira has assessed 28 challenges and been vindicated each time by the referees’ on-field verdicts. “Everybody at Fox is waiting for me to miss one and see how I react,” he said, adding that he has a statement for the Sunday a referee contradicts him: “For those people who think replay takes judgment out of the play, this call proves that wrong.”

Pereira’s move to Fox began during the 2008 season when the network’s NFL insider, Jay Glazer, reported that Pereira would retire after the 2009 season. “Maybe 40 minutes later my phone rang and it was David Hill” — the chairman of Fox Sports — “who said that ‘this retiring stuff is nonsense; you’ll do something for us.’ But my role was not decided until after the 2009 season.”

Eric Shanks, the president of Fox Sports, said Pereira’s on-air role was purposely limited.

“The worst thing would be to overuse him,” Shanks said. “We don’t bring him in on every challenge. We force our announcers to know the rules.” (But sometimes, as in the Green Bay-Jets game, they do not.) He added, “His talking to producers and talent really keeps us honest.”

Pereira’s on-air role is similar to the one played by David B. Fay, the executive director of the U.S. Golf Association, who interprets rules for NBC on the U.S. Open. A predecessor, Frank Hannigan, did the same thing for ABC, then joined the network.

The ranks of on-field or on-court arbiters who have become commentators are thin and include the baseball umpires Ron Luciano and Steve Palermo; the NBA referees Richie Powers and Mendy Rudolph; and Bill Chadwick, the hockey referee called the Big Whistle, who was a radio and TV analyst for the Rangers. ESPN last month hired the former umpire Jim McKean for studio work in the postseason.

Why so few? Lou Oppenheim, an agent for TV sports and news talent, said, “I have to guess that nobody wants a former employee telling umpires or referees that they’re screwing up.”

Shanks suggested that there were not enough rules controversies and video-replay opportunities to make hiring an umpire worthwhile for baseball telecasts.

While Shanks may be correct, a savvy umpire who has viewed the world from the four corners of the diamond might have plenty to say besides rules interpretation.