Technologically retro vinyl records have never been cooler

Published 5:00 am Saturday, September 25, 2010

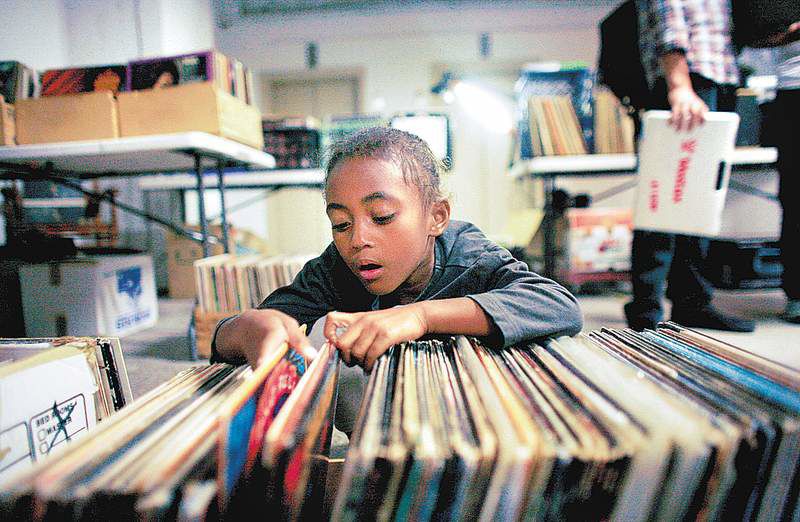

- Philip Cooper, right, speaks with vendor and DJ Matthew Radune at the Brooklyn Flea record fair in New York on Sunday. Vinyl record sales are growing: In 2008, 1.88 million vinyl albums were purchased, more than in any year since Nielsen SoundScan began tracking sales nearly 20 years ago.

NEW YORK — Where were the vinyl widows on Sunday? Were they off doing yoga or out in a park enjoying the beautiful late-summer weather, or taking a break from the crates and stacks and piles of 33-rpm records they share with some vinyl fanatic?

Everyone knows the type. It is now a cliche. It is so much a cliche of early 21st century hipster life that the locavore played by Mark Ruffalo in Lisa Cholodenko’s film “The Kids Are All Right” is defined as much by his mania for music on plastic platters as for his passion for vegetables with a biography.

The numbers of vinyl fanatics are hard to measure, but what’s certain is that they are growing, along with vinyl record sales. In 2008, 1.88 million vinyl albums were purchased, more than in any year since Nielsen SoundScan began tracking sales nearly 20 years ago.

That figure may be a numerical flyspeck compared with the volume of digital downloads purchased during the same period. Yet the folks at SoundScan were not alone in noting that a generation raised on MP3 players has lately fallen in love with long-playing records, as well as the charmingly outdated technology that was the primary means of playing music at home for the better part of a century.

Check out the YouTube videos of Fisher-Price’s green and yellow Big Bird record player, the one that has Big Bird’s beak on the tone arm, and you’ll see what I mean.

Mass retailers like Urban Outfitters have taken note and now sell vinyl records and record players in their stores. The Gagosian Gallery caught on to the burgeoning market and has added vinyl records with covers designed by artists to the offerings at its Gagosian shop on the Upper East Side. Menswear designer John Varvatos, a collector whose personal stash runs to 15,000 records, was onto vinyl early; his store in a Bowery building that once housed CBGB stocks some of the choicest old records in town.

“Vinyl is the biggest it’s been in 20 years,” Varvatos said the other day, adding that between designing and promoting his collections, he stocks the store’s record selection himself. “I’m the buyer,” he noted with a mixture of satisfaction and chagrin.

Most of his finds are unearthed online, he said, pointing out that Web browsing still has nothing on the tactile pleasures of “binning,” that is, spending one’s off-hours flipping through albums in milk crates and bins.

Treasure hunting

It was treasure hunters in the Varvatos mold that one saw leaving the late-summer light Sunday to descend into the purgatorial gloom of the Vault at One Hanson Place in Brooklyn. There, in subterranean chambers, 30 or so vinyl dealers invited by the Brooklyn Flea had set up their folding tables and hauled out their bins.

Sunday’s was not the largest vinyl fair around, or even the largest one that weekend (that probably would have been the Long Island Music Lover’s Faire, held at a VFW hall in Massapequa). But, like a locavore version of the record conventions that occur weekly throughout the country, the Brooklyn version had a distinct flavor of New York. Among the vendors was a senior editor at The Huffington Post; two guys from Other Music, the wonderful indie record store that is the last holdout on a stretch of Bond Street that once was vinyl central; a kindergarten teacher with a sideline selling psych-rock recordings; and Bill Yawien, a 55-year-old from Sheepshead Bay whose recent move from a house to a condo forced him into the kind of difficult life decision Manhattan Mini Storage was created to facilitate.

“It was time to whittle it down a little,” Yawien remarked to some browsers perusing his trove of ancient discs, records by Cream and Jimi Hendrix and the Jefferson Airplane and the Mothers of Invention and also by people so obscure that to anyone under the age of retirement, the titles might as well have been in cuneiform script.

“God bless you for releasing your attachment,” Julie Zimmermann, one of the rare women to be seen wandering through the dim vault, told Yawien.

The truth, though, is that his release of that attachment was open to some debate.

“I kept about 4,000 records,” Yawien noted as he slid a record from its sleeve.

The record was Murray the K’s “1962 Boss Golden Gassers”; a line at the bottom of its jacket described the contents as music to play while watching submarine races. An awful lot of pop cultural history was encoded into that one compilation — with its songs by the Shirelles, Etta James, and the Edsels (“Rama Lama Ding Dong”) — not least that it marked the existence of Murray the K himself, a record- and self-promoter with a taste for straw hats, a knack for affiliating himself with important musical trends of the era and an on-air signature so retro-creaky as to have a kind of “Mad Men” cool.

“This meeting of the ‘Swingin’ Soiree’ is now in session,” K (ne Kaufman) used to proclaim on his radio broadcasts, the ones presumably being played on radios belonging to Brooklyn teenagers of the era as they watched the submarine races from under the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. There were no submarine races, of course. As the Urban Dictionary will inform you, submarine racing is a period euphemism for the stuff you do that steams up the windows of cars.

The music and not the narratives is clearly the reason most people buy old vinyl. They hunt down cult items, weird break-beats, pressings made in small numbers by obscure labels in the places where genres and subgenres first took hold.

“I buy house and Detroit techno, mainly,” said Matt Arace, a DJ, who was hunting down labels like Kompakt or Minus.

“I buy any genre, basically,” said John Rattner, a Bay Area DJ transplanted to Brooklyn, “except techno and house.”

They are searching for things like the Serge Gainsbourg import one buyer found in a bin for $25 or the early Tito Puente and Beny More records he also fell upon. They are, like Jeffrey Joe, who teaches high school in Harlem, “not looking for anything in particular,” which is to say they are putting themselves in the way of serendipity.

Elements of an autobiography

It is safe to assume that buyers like Joe are also, in some subtle fashion, seeking cultural connections, the kind you can only get from someone like Sal Siggia.

Siggia was down in the Vault on Sunday, wearing indigo Katharine Hamnett pants from the ’80s and selling his personal trove from the era, including a nearly complete Smiths catalog, a passel of Wigstock memorabilia and a Sex Pistols T-shirt snagged at a long-ago San Francisco gig.

“Someone once called me a culture maven,” Siggia said. “But I never thought much about what I was collecting. I just knew it was worth saving somehow.”

What felt great to him about Sunday’s market, Siggia added, was that almost everything he sold that day had been acquired not for resale but for personal pleasure.

“Everything people bought was my stuff from the ’80s,” Siggia said, meaning the records that he played or clothes that he wore.

T-shirts from the nightclub Area and a complete collection of Smiths records are, in their own way, elements of an autobiography.

Was it tough, Siggia was asked, to relinquish his treasure, his classics, these relics?

“No,” he said flatly. “Once I decide to let go, I let go. If I dropped dead tomorrow, all this stuff would be out on Avenue A the next day.”