Improving music quality, bit by bit

Published 5:00 am Monday, September 13, 2010

- It’s not too late to improve the sound quality of your digital music collection. Bit-rate settings in iTunes can improve what you hear over your stereo but will eat up more memory on your computer.

If you’ve been building a digital music collection for more than five years, it’s likely filled with an assortment of songs of differing sound quality.

Maybe some come through the speakers with a more full sound, richer bass tones or clear high notes at the top of the scale.

Trending

Many factors affect music quality, from how it’s recorded to what equipment it will be played on, and many steps in between, audio experts say.

But even casual listeners who can’t distinguish between mono and stereo can potentially improve music quality coming from their digital music player by changing one setting: the bit rate.

By increasing the bit rate in the preferences of Apple’s iTunes, Nullsoft’s Winamp or other music players, you can improve the sound quality for any future CDs imported to your digital collection. And older CDs can be re-imported at the new setting as well.

Increasing the bit rate has one drawback, however.

It increases the size of the music file, taking up more room on a hard drive, iPod and other portable music players, and potentially reducing the total number of songs that can be stored.

But Steve Hartwell, lead audio engineer and owner of Featherlight Recording Studio in Bend, thinks it’s worth it.

Trending

The explosion of digital technology has led to lower-quality music as consumers become obsessed with the number of songs they can collect, rather than how the music sounds, Hartwell said.

“It’s the first time in musical history we’re actually going downhill in musical quality,” he said.

Hartwell is not alone. For several years, audiophiles and digital music aficionados have carried on Web debates about the relative sound quality, or lack of it, found in the alphabet soup of audio file types, known by their extensions: “aac,” “wma,” “rax” and the most commonly used, MP3.

Creation of MP3s

While MP3 became synonymous with digital music players — which were frequently called MP3 players — it actually stands for MPEG-layer 3, a file extension, according to the website for the Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits, which developed the MP3 audio encoding software built into iTunes, Windows Media Player and others. Think of MP3 as equivalent to “txt,” for a text file, or “jpg,” for a picture file.

In the ancient days of digital communication — the 1980s and early ’90s — experts searched for a way to send music over telephone lines.

Professors and students at the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany, later joined by others, developed a way to compress the audio files, making them smaller, so they could travel faster and take up less space, yet still produce CD-quality sound.

For example, three minutes of compressed music could fit on a single 3.5-inch floppy disk, for those who remember floppy disks. Decompressed, it took up a dozen disks, according to the Fraunhofer website.

MP3 encoding also saved space on the relatively small hard drives — sometimes 100 megabytes or less — found in personal computers in the early 1990s.

During compression, however, some of the information — or music — gets lost. The sound at either end of the spectrum, during the quietest and loudest sections, gets stripped out, Hartwell said.

The bit rate represents how much of the sound from the original source gets captured when creating the tracks, according to Apple. But it also affects the size of the music file. An MP3 file imported at 192 kilobytes per second will be larger than a filerippedat 128 kbps.

Some of the music players and programs that came with computers a decade ago, by default, imported music from a CD at 96 kbps, or even less.

Most personal computers available today come with hard drives measured in gigabytes, so file size may be less of an issue than it was 20 years ago.

With iTunes — the free digital music player provided by the nation’s leading music retailer, according to a May report by market research firm The NPD Group — it’s easy to set the bit rate for music imported from CDs.

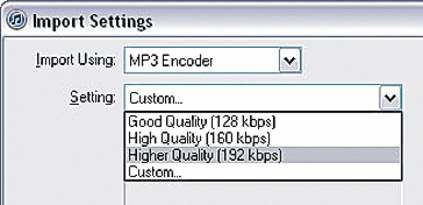

In the Edit menu of iTunes 9 and 10, select “Preferences” and click on “Import Settings” on the “General” tab. For importing MP3s, it offers three bit-rate settings: 128, 160 and 192 kbps. iTunes also provides different options for other file types and custom bit-rate settings.

All things being equal, the higher the bit rate, the better the sound quality.

Why stop there?

You can also check the bit rate of the music currently in your iTunes library.

To learn about an individual song, highlight it in the music list, go to the “File” menu and click on “Get Info.” The window that pops up will have a summary of information, including the bit rate.

To find all songs in the library below a certain bit rate, create a Smart Playlist, which essentially searches iTunes’ music library for the criteria the user selects and returns all matching songs.

For example, to find all songs with a bit rate below 128 kbps, go to the “File” menu and select New Smart Playlist. Check the box next to “Match the Following Rule” box, select “Bit Rate” from the first drop-down menu; choose “is less than” from the second and enter 128 in the adjoining box.

To make the bit rate show in the playlist window, select “View Options” on the “View” menu, and check the box next to “Bit Rate.”

If you haven’t given away all the CDs you imported to your hard drive in years past, you can simply re-import them at the higher rate. If the computer’s hard drive is nearly full, however, adding a slew of larger music files may not be advisable.

In a quick test, a file imported at 192 kbps doubled in size over one ripped at 96 kbps. The same file imported using Apple’s compression method, called Lossless, grew more than tenfold in the test. Apple says the Lossless method preserves CD-quality sound while still shrinking the file size over an uncompressed file.

Other music players offer similar ways to check the bit rate.

Currently, iTunes only sells songs with a 256 kbps bit rate, and Apple will even allow you to upgrade your lower-quality purchased music — for 30 cents per song. But at least they can be upgraded.

If you’ve been building a digital music collection for five years or more, you probably have some files purchased from now-defunct online music sites that cannot be played at all.

Boosting bit rates will not magically fix the sound quality of a digital music library. The system playing the music — the speakers, the way it was recorded, the type of file — all can have a huge effect on quality, Hartwell said.

But on a decent system, which can even be found in many new home computers, he believes listeners should be able to hear the difference between one MP3 file imported at 96 kbps and another at 256 kbps.

Improving the sound quality means hearing more of the music’s emotional message.

“Music is about emotion,” Hartwell said. “It doesn’t matter what kind. It’s a form of communication. If we start to lose the emotional content … we’re doing a disservice to everybody.”