Conger campaign: A family affair

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 26, 2010

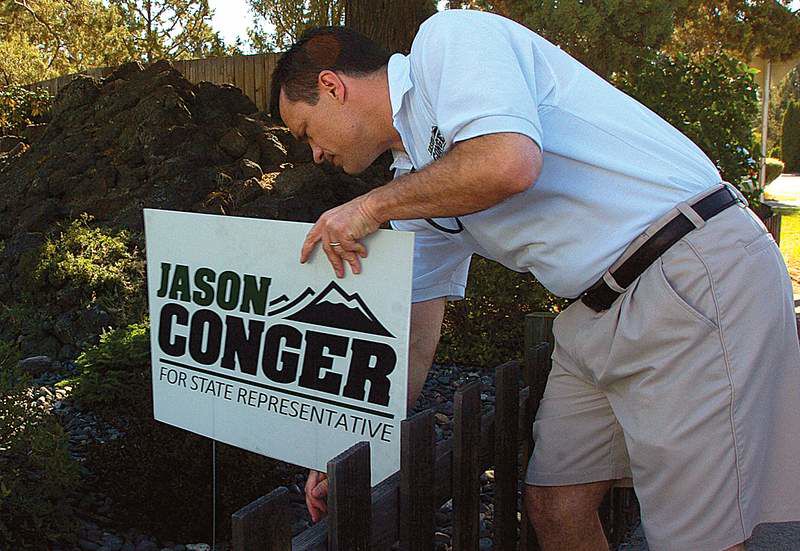

- Conger places a campaign sign in the front yard of a supporter while walking door to door in a northeast Bend neighborhood Saturday.

After months and months of campaigning for the Oregon House of Representatives, Jason Conger has learned all about the hazards of making pledges he might not be able to keep.

Like the one to his 11-year-old daughter, Maddy, about the horse she may or may not be getting after the campaign is over.

“I was very vague with the specifics on that, so I have a lot of years to fulfill that promise,” Conger said Saturday morning, campaigning door to door with his family and a core group of supporters in northeast Bend.

Bounding up a driveway toward yet another doorstep, he paused and turned to Maddy.

“I didn’t really promise you a horse, did I?”

Conger, 42, is the Republican challenger to state Rep. Judy Stiegler, the Democrat who won her seat in 2008 by ousting two-term incumbent Chuck Burley. Conger and Stiegler will be joined on the ballot by an independent candidate, Michael Kozak, a Bend city councilor from 1984 to 1993.

A Harvard law graduate and an attorney at Miller Nash LLP in Bend, Conger filed for office more than a year ago and has been actively campaigning since February. His wife, Amy Conger, 39, said they set a goal of visiting every household in Bend at least once, and after 18,000 visits, they think they’re about halfway there.

Their son, 19-year-old Jacob Conger, heads up the campaign’s door-to-door efforts. Saturday morning, Jacob assembled a group of around 15 volunteers, passing out maps, campaign literature, lists of voter names, addresses and registrations, and bottles of water for three hours of knocking on doors and talking issues with prospective voters.

Enthusiastic supporters are lined up for lawn signs. Undecided voters are noted, possibly to receive an extra campaign mailing, a phone call or another in-person visit to try to secure their vote. Those planning to vote for another candidate are thanked for their time.

Blame it on the weather

Most get nothing more than a glossy card with the candidate’s picture and positions, tucked inside their door frame. Sunny weather reliably drives down the number of people he meets when the campaign goes door to door, Conger said, and with the number of nice days rapidly dwindling, it’s no surprise he’s only been able to find a handful of voters at home.

Door-to-door campaigning every Saturday and a few days midweek has helped Conger drop around 10 pounds, and supplied him with a wealth of stories from voters. In newer neighborhoods, where most of the homes were built and bought near the peak of the real estate market, he’s found voters anxious about the declining value of their homes. In semirural parts of the district, like Deschutes River Woods, he’s come across families that are doubling up with unemployed adults living in RVs on their parents’ property.

The more emotional stories can go on and on, he said, but listening is part of the process of running a campaign.

“I gotta tell you, when someone’s in distress, talking about their divorce or their family, or whatever, I don’t really feel comfortable saying, ‘I gotta go now,’” he said.

Voter Jerry Mitch was an easy sale, cutting off the candidate in mid-sentence.

“Hello, I’m Jason Conger, and I’m running for the Oregon … ”

“And I’m voting for you,” Mitch responded.

Mitch, 56, owns an insurance agency in Bend, considers himself a conservative, and said he looks for candidates with a commitment to fiscal responsibility, family values and the preservation of individual rights.

Conger seems like such a candidate, Mitch said, and he likes his chances for winning in November.

“I think there’s a big backlash coming against the Democrats, and I think it’s well deserved,” he said.

The quiz

Becky Taillon was more skeptical, quizzing Conger on his reasons for running and his ideas for closing the state’s budget gap. When Conger offered up two items he would look to cut, a $2 million state study on reducing carbon emissions and a $500,000 subsidy for the Portland Art Museum, Taillon shot back, noting that both items make up only a tiny fraction of the state’s budget.

Taillon, a 34-year-old chemical engineer, said she agreed with Conger that schools and public safety should be the state’s top priorities, but hasn’t yet decided who will get her vote. Finding useful information about candidates is often difficult, she said, and she wanted to make the most of meeting one face to face.

“If I have the person right on my doorstep, I want to at least ask a few questions about issues to see if he’s thought of it,” Taillon said. “As a politician, you should at least be able to answer basic questions.”

Taillon observed that Conger’s campaign flier makes no mention of the Republican party, something Conger said was a conscious choice by the campaign. Committed party voters will often shut down upon meeting a candidate from a competing party, he said, but by keeping his party off the flier, he’s able to start a conversation and hopefully find a few areas of agreement.

“I hope to get a chance to talk to people about our principles and ideas and what we hope to accomplish, and try to convince them to vote for me based on that, rather than just based on party,” he said.

Conger has been a Republican since before he could vote, an affiliation that began with him watching Ronald Reagan on television as a teenager. At first, it was purely an emotional attachment, Conger said — Reagan made him feel good about being an American, and optimistic about the future — but it led to an interest in, and eventual adoption of, a conservative outlook.

Republican rebellion

Registering as a Republican when he turned 18 was an act of rebellion in the Conger family, and he’s largely avoided talking politics with his parents since.

“I grew up in a very liberal household, and my dad in particular was very vocal about not liking Ronald Reagan,” he said. “And I never for the life of me could figure out why.”

John Philo, 60, one of Conger’s volunteers, said he only developed a serious interest in politics in the last 11⁄2 years. A contractor specializing in remodels, his business dropped off by more than half with the slowing economy, giving him plenty of free time and a nagging sense that “everything was going in the wrong direction.” Campaigning is one of the only ways one person can make a difference, he said.

“I’m just concerned with the growth of government, because government can suck the life out of business and people’s lives,” Philo said. “Of course, government can do good things, but we keep feeding this ever-growing beast.”

Ralph Ferguson, 50, has been volunteering for Conger for months, going door to door and serving as media coordinator, even though he lives in Redmond and will not be able to vote for him. Outside of multiple voters who’ve asked if he’s Conger’s father, it’s been a great experience — and while he’s excited about the final push to Election Day, he doesn’t really want to see the fun come to an end.

“It will be a letdown come November not to have that camaraderie,” Ferguson said. “But, in two years, you’ve got to do it all over again.”