Richardson’s Rock Ranch

Published 5:00 am Saturday, July 31, 2010

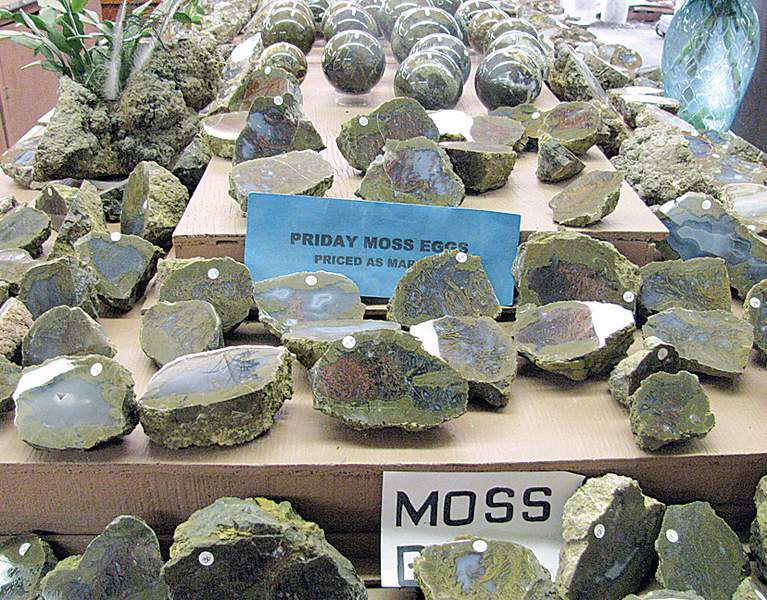

- Cut thundereggs from one of the Priday beds are on display in the rock shop.

Richardson’s Rock Ranch — with its colorful, agate-filled nodules known as thundereggs — is rich in geologic history.

And with roots reaching back to the 1800s and three generations of family running the place, Richardson’s is plenty rich in human history as well.

Since they opened their rock shop in 1974 and purchased the famed Priday agate thunderegg beds from a neighbor in 1976, Johnnie and Norma Richardson, both 81, have amassed a 17,000-acre spread northeast of Madras that is a rock hound’s delight. Visitors day-tripping from Bend and Portland join rock hounds who come from around the world to hunt for moss agate, jasper and Priday plume thundereggs, just some of the rocks to be found there.

About 30 percent of visitors never make it past the rock shop, says Bonnie Richardson, Johnnie and Norma’s daughter-in-law. Bonnie, 54, is married to their son, John, 57. Casey Richardson, 24, one of John’s four children from a previous marriage, has followed in the family footsteps. He works at the ranch along with his soon-to-be wife, Heather Coonse, from Prineville.

Along with exporting rock from Central Oregon, the Richardsons import rough rock from China, Africa, South America and elsewhere. There are geodes from Brazil, petrified wood from Madagascar and starfish fossils from Morocco.

There are also so many things made from rock here that it almost calls to mind the town of Bedrock from “The Flintstones,” where everything was made from stone, the show being set in the Stone Age. There are lamps, jewelry, wind chimes, paper weights, bookends and even, yes, the kitchen sink.

“How do you like (the) sinks down by your feet?” asks Johnnie, sitting at a nearby table made from rock. “Those are made from petrified wood in Indonesia.”

The shop has been open seven days a week, 365 days a year, for 36 years. In the early years, the Richardsons note, it was open 24 hours a day and allowed free camping. Camping is no longer permitted on the premises, and the ranch is open 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the warm months and 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Nov. 1 through March 1.

“We are all on vacation from 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. every day,” Bonnie says.

There are tables devoted to spherical rocks that look like miniature moons, perfectly shaped using equipment specially developed by John. The Richardsons don’t sell those sphering devices anymore, but they still make and sell the Richardson buffer and high-speed dry sander.

Pestered by rock hounds

Norma is the native. The house next door to the rock shop was built in the 1860s by the Veazie family, friends and neighbors to Norma’s great-grandparents.

“Every once in a while in that house you can hear Mr. Veazie walking around, or he opens doors,” Johnnie says.

“We laugh and say he opens and shuts doors,” Norma adds. “He’s a very good ghost.”

The house still stands next to the rock shop. It’s fallen into disrepair; now the only inhabitants — besides Veazie’s ghost — are the Richardsons’ peacocks, which like to perch on the porch.

For decades, the Richardson family was about cattle ranching, not rock ranching. In fact, back in the 1920s, Norma says, rock hunters were a nuisance to be shot at.

Really?

“Oh, absolutely. When I was a kid, they were pests,” she says.

Both Norma and Johnnie attended one-room schoolhouses. He was raised in Lakeview.

“He’s a newcomer; he’s only been here 60 years,” says Norma.

Johnnie and Norma met 62 years ago, in 1948, at a livestock-judging class in Corvallis.

“She was one of the heifers that they let in,” says Johnnie, whose quiet demeanor masks a born joker.

Don’t feel too bad for Norma, who takes his crack in stride. Johnnie soon turns the jokes on himself: “Everywhere I’ve gone, she’s gone along with me. And I asked her why the other day. She said I was too ugly to kiss goodbye.”

Some of his jokes — like the ones explaining how he earned the title “resident character” — his wife asks that we don’t print.

Until 1957, they worked for Norma’s parents. They next leased the ranch for a while, buying it outright in 1962. “It took us 42 years to pay it off,” she says.

However, trouble befell their cattle operation in 1972, when bovine tuberculosis was discovered on the ranch.

“We had to get rid of all of our livestock because two of our cows had TB,” Norma says. “It was just one of those things where, if you ate 700 pounds of raw red meat in one day, you might get TB from it. It was a government thing.”

“They liquidated over 1,500 head” of cattle, says Johnnie.

Rock hounds had started coming around their corner of Central Oregon after a 1967 rock magazine wrote about the area’s rich agate offerings. Then they were told they were sitting on a million dollars.

“In 1966, a fella from over here in Culver kind of explored as to what was around up there,” says Norma. Then one day in 1967, Johnnie went out to the mailbox, where a man named Ovid Brooks, of Portland, was looking at rocks on the ground. He told Johnnie, “You guys need to do something with your rocks.” This wasn’t the more far-flung Priday beds, she stresses, but land that features jasper and other rock beds.

“It was land that my grandfather had bought for next to nothing, back before 1900,” Norma says. “We’ve often laughed and said that Grandpa Crabb would have really turned over in his grave if he could see what we’re doing with it now.”

‘We’re in the rock business’

In 1974, they bought out the inventory of a rock shop in Redmond, and went into the rock business.

“See, most rock shops are run by rock hounds,” says Norma. “None of us are really rock hounds. We’re in the rock business.”

At first, “we played with the thing, never intending to do what we’re doing now,” Norma says,

That’s not to say they don’t value many of the rocks, she says. There’s a museum-like display area in a room separate from the main shop where they’ve put rocks sent to them as gifts.

“It’s not because we want to keep them for us; it’s because they were gifts to us, and you can’t sell something that somebody gives you,” she says.

Though her grandson Casey is working at the rock ranch, being born into the Richardson family doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll be working with rock, says Norma.

Back when they were in the cattle business, baling hay was misery for their son John, who has hay fever.

“He could mow the lawn and be stuffed up for two days,” she says. He was away at college when the bovine TB incident occurred and he came home to help out.

“At the same time, we were raising pheasants for a shooting preserve, and he never had time to get away,” Norma explains. “Been here ever since.”

John was off working when The Bulletin visited, but Bonnie explained that when John became interested in sphering rocks, he bought a two-headed sphering machine, but it became quickly apparent it wasn’t going to work.

John and Johnnie “got their heads together and designed the three-headed machine,” Norma explains. “He started making spheres, and he loves it better today than he did yesterday. He’s been doing it for 30 years.”

Although sphered rocks pepper the shop, about 80 percent of his sphere production is custom work for others. “That’s when we get to see the variety,” says Bonnie.

John has the rock knowledge and does a lot of the buying for the shop. “He always says, ‘I bought ’em, now you guys gotta sell ’em,’ ” Norma says. “Johnnie and I like people, and our son can only take so much of them.”

Johnnie liked people so much that, for many years, he would trade them a Richardson’s Rock Ranch ball cap for whatever one they walked in wearing. He’s amassed some 3,000 of them; 1,200 hang in the ceiling in the back portion of the shop.

Bonnie could be considered the family’s biggest rock hound, “but not to the point of not being able to sell them,” Norma says.

Bonnie has four kids of her own from a previous marriage, and she and John met through their kids, she said.

“I love the rock. I married this,” says Bonnie.

Though shipping and buying rock helps keep them busy year-round, summer is the time of year when they work with tourists.

“When they quit coming in the fall, you think they’re never coming back,” Johnnie says. “In the spring you think they’ll never leave.”

Big claim to fame: the thundereggs

Thundereggs, of course, are the Richardson’s big claim to fame. After a day or few hours of rock hounding, visitors can bring their rocks back to the shop to have them cut in half.

Nobody agrees about how thundereggs were formed, Johnnie says. “You can ask 12 different people and they’ll give you 12 different ways.

“We say, for simplicity, that they were formed as a gas bubble in a rhyolite flow about 60 million years ago. The old volcano was bubbling away. … These were gas bubbles that come up through and they didn’t burst when they got to the top.”

A later eruption involving the volcanic glass perlite would cover those rocky bubbles. “Perlite is high in silica, and as the water percolated through, it carried the silica, which filled those bubbles,” he says.

“We say that better than 65 percent of all thundereggs in rock shops all over the world originate on this ranch,” Johnnie boasts. “There’s hardly a country that we don’t export to, and hardly a country we don’t export from.”

The thunderegg-rich Priday beds, named for a family that got out of the business in 1944, went through a series of owners before the Richardsons acquired them in 1946.

Priday plume, with colors that resemble feathers, is a type of thunderegg that Norma calls the “diamond of the thunderegg family.” The bed it comes from has been mostly closed for the past 15 years due to safety concerns. Digging into the walls of the bed is dangerous, and decades before they owned that portion of land, three people died there.

The Richardsons plan to open it for just the third time this year on Labor Day weekend “under supervision,” Norma says. Normally, their digging beds are unsupervised, but the Richardsons will have someone at the plume bed to help those seeking rocks dig in safe places.

There are larger digging beds, and larger rock shops, but with the sale of rough and finished rock as well as their machinery, it’s safe to say that they have one of the larger operations going.

Business has been good, despite the economy, Bonnie says. “It’s been amazing. I think with the economy, our clientele has changed in that they’re more local. … Now people from Bend are coming in droves. But we don’t get as many people from back east as we used to.” Recent visitors have also come from California, Washington and Idaho.

When one shopper reveals his home is California, Norma replies — mostly good-naturedly — “My sympathy.”

She still loves her lifelong home, and the nearby volcanic range that seems so emblematic of the family’s work of the past 36 years. “Isn’t it beautiful?” she says.

Norma and Johnnie have to get up and go to Redmond at 4:30 a.m. three days a week so he can get dialysis treatment. She accompanies him on those morning drives.

“This summer, those mountains have just been magnificent, especially when the sun’s coming up,” she says. “I’ve lived here all my life, I’ve seen them forever, and still, I’m in awe of them.”

If you go

Richardson’s Rock Ranch is located 11 miles north of Madras at 6683 N.E. Haycreek Road. Take U.S. Highway 97 north from Madras and watch for signs to Richardson’s. It’s open daily from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. (9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Nov. 1 through March 1).

Contact: 541-475-2680 or richardsonrockranch.com.