J.D. Salinger, reclusive author of ‘Catcher in the Rye,’ dies

Published 4:00 am Friday, January 29, 2010

- J.D. Salinger, author of “The Catcher in the Rye,” died on this day in 2010 in Cornish, New Hampshire, at 91.

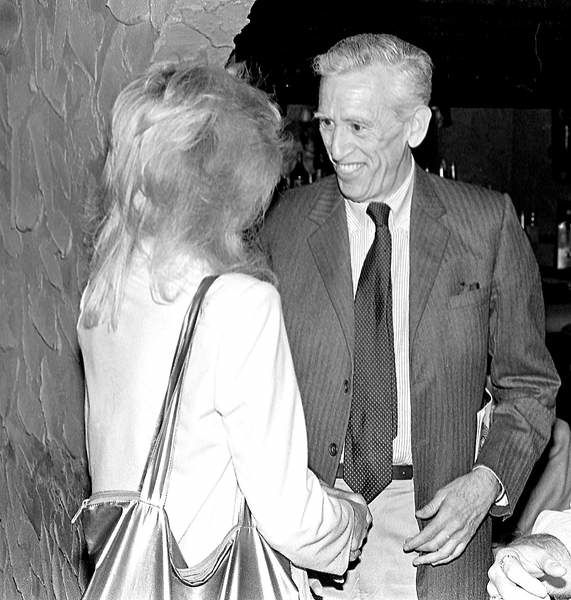

J.D. Salinger, who was thought at one time to be the most important American writer to emerge since World War II but who then turned his back on success and adulation, becoming the Garbo of letters, famous for not wanting to be famous, died Wednesday at his home in Cornish, N.H., where he had lived in seclusion for more than 50 years. He was 91.

Salinger’s literary representative, Harold Ober Associates, Inc., announced the death, saying it was natural causes. “Despite having broken his hip in May,” the agency said, “his health had been excellent until a rather sudden decline after the new year. He was not in any pain before or at the time of his death.”

Salinger’s literary reputation rests on a slender but enormously influential body of published work: the novel “The Catcher in the Rye,” the collection “Nine Stories” and two compilations, each with two long stories about the fictional Glass family.

“Catcher” was published in 1951, and its very first sentence, distantly echoing Mark Twain, struck a brash new note in American literature: “If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.”

Though not everyone, teachers and librarians especially, was sure what to make of it, “Catcher” became an almost immediate best-seller, and its narrator and main character, Holden Caulfield, a teenager newly expelled from prep school, became America’s best-known literary truant since Huckleberry Finn.

With its cynical, slangy vernacular voice, its sympathetic understanding of adolescence and its fierce if alienated sense of morality and distrust of the adult world, the novel struck a nerve in Cold War America and quickly attained cult status, especially among the young. Reading “Catcher” used to be an essential rite of passage, almost as important as getting your learner’s permit.

The novel’s allure persists to this day, even if some of Holden’s preoccupations now seem a bit dated, and it continues to sell more than 250,000 copies a year in paperback. Mark David Chapman, who killed John Lennon in 1980, even said the explanation for his act could be found in the pages of “The Catcher in the Rye.”

Philip Roth wrote in 1974: “The response of college students to the work of J.D. Salinger indicates that he, more than anyone else, has not turned his back on the times but, instead, has managed to put his finger on whatever struggle of significance is going on today between self and culture.”

Many critics were even more admiring of “Nine Stories,” which came out in 1953 and helped shape later writers like Roth, John Updike and Harold Brodkey. Updike said he admired “that open-ended Zen quality they have, the way they don’t snap shut.”

As a young man Salinger yearned ardently for attention. He bragged in college about his literary talent and ambitions, but success, once it arrived, paled quickly for him. He told the editors of Saturday Review that he was “good and sick” of seeing his photograph on the dust jacket of “The Catcher in the Rye” and demanded that it be removed from subsequent editions. He ordered his agent to burn any fan mail.

In 1953, Salinger, who had been living in Manhattan, fled the literary world altogether and moved to a 90-acre compound on a wooded hillside in Cornish.

The more he sought privacy, the more famous he became, especially after his appearance on the cover of Time in 1961.

In the ’80s, Salinger was involved with the actress Elaine Joyce, and late in that decade he married Colleen O’Neill, a nurse. Not much is known about the marriage because O’Neill embraced her husband’s code of seclusion.

Besides his son, Matthew, Salinger is survived by O’Neill and his daughter, Margaret, as well as three grandsons.

What’s in Salinger’s safe?

NEW YORK — The death of J.D. Salinger ends one of literature’s most mysterious lives and intensifies one of its greatest mysteries: Was the author of “The Catcher in the Rye” keeping a stack of finished, unpublished manuscripts in a safe in his house in Cornish, N.H? Are they masterpieces, curiosities or random scribbles?

And if there are publishable works, will the author’s estate release them?

The Salinger camp isn’t talking.

No comment, says his literary representative, Phyllis Westberg, of Harold Ober Associates Inc. No plans for any new Salinger books, reports his publisher, Little, Brown & Co.

Marcia Paul, an attorney for Salinger when the author sued last year to stop publication of a “Catcher” sequel, would not get on the phone Thursday.

His son, Matt Salinger, referred questions about the safe to Westberg.

Stories about a possible Salinger trove have been around for a long time. In 1999, New Hampshire neighbor Jerry Burt said the author had told him years earlier that he had written at least 15 unpublished books that he kept locked in a safe at his home.

A year earlier, author and former Salinger girlfriend Joyce Maynard had written that Salinger used to write daily and had at least two novels stored away.

— The Associated Press