Study shows little change in junk food ads for kids

Published 4:00 am Thursday, January 14, 2010

- Study shows little change in junk food ads for kids

Most of the food ads on Nickelodeon are for junk food.

That’s the conclusion of a recent study published by the Center for Science in the Public Interest, which looked at the content of ads on the nation’s most-watched children’s network.

The study found nearly 79 percent of food ads were for foods with poor nutritional quality. In 2005, a similar study by CSPI found that 88 percent of food ads on Nickelodeon were for junk foods.

The decline in junk food ads is encouraging, but not enough, said lead author Margo Wootan. “It shows a ray of hope but is certainly not the magnitude of change that’s needed given what a huge problem childhood obesity is.”

Nickelodeon did not return requests for comment on the study.

As most parents can attest, food marketed to children has the power to influence what they want and are willing to eat. Experts, Nickelodeon and food manufacturers have all called for responsible marketing to curb the epidemic.

That new study implies that may not be happening.

Company promises

In 2006, many of the nation’s largest food manufacturers signed on to an initiative of the Council of Better Business Bureaus, the national headquarters for local bureaus, to regulate their own food advertising to children.

Each company developed nutritional standards and agreed not to market products to children that did not meet those standards.

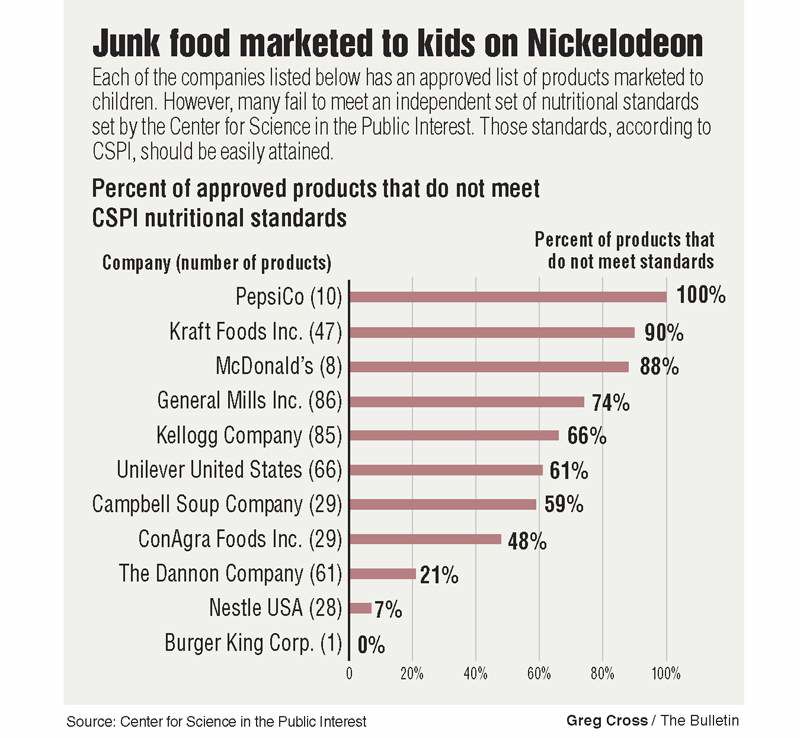

The companies, said Wootan, are doing a good job of complying, with virtually no products marketed to children falling below each company’s own nutritional standards.

The problem, she said, is the standards themselves. Because companies set individual standards, they can modify them. So cereal makers can tweak the sugar up a bit, while fast food restaurants may have reasonable sugar standards but be lax on sodium.

“Those standards have loopholes,” said Wootan, “strategic loopholes.”

The recent CSPI study evaluated the nutrition of foods based on an independent standard developed by experts for CSPI. Those standards, said Wootan, “are really mediocre.”

Nevertheless, many of the products marketed to children do not meet even those modest nutritional requirements, she said.

McDonald’s, for example, has its own nutrition standards developed under the initiative. However, according to the study, 88 percent of the company’s ads on Nickelodeon did not meet CSPI’s nutritional standards.

A spokeswoman for McDonald’s said the company has a commitment to nutrition for children. “We feel like we are very responsible with the marketing that we do, especially to kids,” said Rebecca Hary.

Hary said that Happy Meals, for example, give children a choice of milk to drink and fruit sticks as a side dish.

General Mills, which also has standards developed through the initiative, said through spokeswoman Heidi Geller that it had no comment on CSPI’s findings. The study showed 74 percent of General Mills food marketed on Nickelodeon did not meet CSPI’s nutrition standards.

Kellogs, in which 66 percent of food marketed did not meet the CSPI standards, did not return requests for comment.

Media responsibility

The other half of the equation, the media companies, also need to strengthen their commitment, Wootan said.

Nickelodeon has taken some steps to address the content of their programming, Wootan said, but not the ad content.

In testimony to Congress in 2008, Marva Smalls, executive vice president of Nickelodeon, said the company’s “ongoing efforts to promote health and wellness and combat childhood obesity demonstrate our commitment to kids, parents and families.”

However, though she described many initiatives within programming to promote healthy lifestyles, only a small portion of her testimony was devoted to advertising. Here she described a need to comply with a set of loose regulations around food advertising that do not discuss specific nutritional content and praised the efforts of companies to self-regulate.

Wootan said more may need to be done to ensure the food marketed to children meets basic nutritional goals. A universal set of standards, perhaps set by Congress, she said, may be the answer.

“As it’s practiced, the self-regulation by companies isn’t working.”